"From the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli": this triumphant beginning to the US Marine hymn will be sung from barracks in Baghdad to parades in Baltimore today, on the 232nd anniversary of America's independence. But those who celebrate the triumph at Tripoli two centuries ago may be unaware of how relevant the victory remains. While the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 officially marked the birth of America, it was in Tripoli, almost 30 years later, that the nation made its debut on the world stage.

During America's War of Independence, the French had provided protection against piracy for merchant vessels from America, bringing cotton, indigo and tobacco to Mediterranean ports. After the war, without French protection, the nation had no defence against piracy. With a military victorious but battered by eight years of war, the fledgling nation could not afford an armed response to tribute demands from North African aggressors.

But infant America did not experience hostility from every North African navy. In 1777, well before it was clear that the American rebellion against Britain would succeed, Sultan Sidi Muhammad Bin Abdullah of Morocco recognised the United States and encouraged trade between the two countries. In 1783, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and John Jay urged the US Congress to reciprocate: "Our trade to the Mediterranean will not be inconsiderable, and the friendship of Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli may become very interesting in case the Russians should succeed in their endeavours to navigate freely into it by Constantinople."

Perhaps with the Moroccan example in mind, the US reached out to other states along the Barbary Coast. While the Sultan of Morocco hoped to boost his economy through increased trade, the leaders of other Barbary states, Tripoli in particular, sought another means to increase revenue: piracy. America would find as many adversaries as allies on the North African coast. In 1786, Thomas Jefferson, then Ambassador to France, and John Adams, the Ambassador to Britain, met an envoy from Tripoli in London, Sidi Haji Abdrahaman, to secure a treaty. Instead of trade, Tripoli sought tribute. Without a functioning navy, without a president and without a constitution to define the powers of its military, the US had to assent to the envoy's demands.

When Jefferson became the third President of the United States 15 years later, he had not forgotten about Tripoli. How could he? The country was still paying as much as one million dollars a year to protect its ships from piracy - a massive sum, given a total annual budget of about $6 million. But by the time Jefferson became President, the US was considerably stronger, with a resurrected navy and a constitution.

In his first inaugural address, Jefferson told the American people that he sought "peace, commerce, and trade with all nations", but the Pasha of Tripoli had different ideas. Tripoli celebrated Jefferson's inauguration by demanding an additional payment of $225,000 to ensure the continued safety of American shipping. Not only did Jefferson find tribute abhorrent to the liberties he had written about in the Declaration of Independence 25 years earlier, but also the payments interfered with his own priorities for the nation - including expanding it westwards into the vast expanses of North America. With Napoleon selling off many of France's American possessions to finance his military campaigns, Jefferson had an opportunity to extend the nation all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

Instead of declaring war, Jefferson refused Tripoli's demands and prepared to respond to any acts of aggression that might result. In his first speech to Congress, he announced the American response to Tripoli: "the style of the demand admitted but one answer. I sent a small squadron of frigates into the Mediterranean." Three thousand miles from the American coast and without the maritime knowledge that the French and British had gained over the centuries, the American navy was ill-prepared for a full-scale conflict, but the Americans hoped to bring the Pasha to the negotiating table by blockading Tripoli.

The considerable show of naval force eventually persuaded all other states on the North African coast to allow American vessels to travel without harassment. Tripoli, however, would not be deterred by a show of strength alone. Jefferson wanted it known that the naval action in North Africa was not about religion. A previous treaty with Tripoli, in 1796, unanimously agreed to by the US Congress, declared: "no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries".

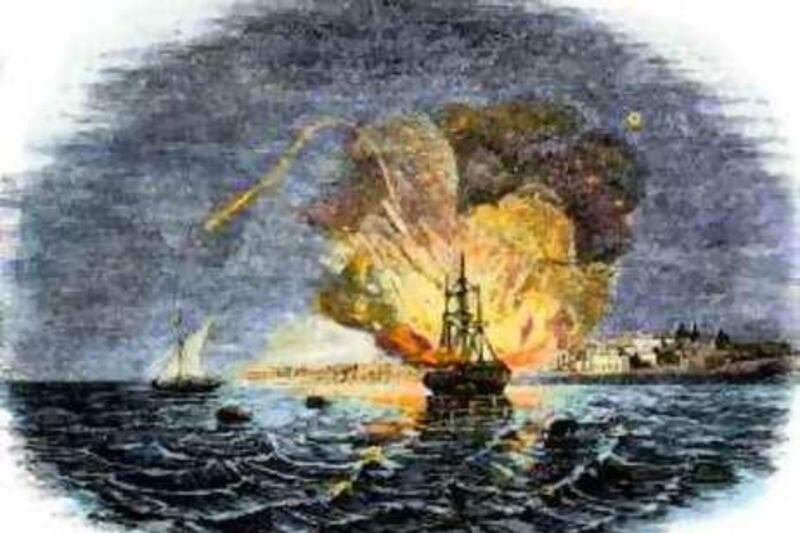

Jefferson had studied various legal traditions, including Islamic law, and kept a copy of the Quran. While serving in the Virginia legislature he wrote in a Bill for Religious Toleration that "Almighty God hath created the mind free, and manifested his supreme will that free it shall remain". A spirit of tolerance, on both sides, was critical to America's long awaited success in North Africa. In 1803, the US Navy was dealt an embarrassing blow in the capture of one of its frigates, the USS Philadelphia, and, after it experienced mixed results from blockading, it became clear a bolder strategy was required. An alliance with Arab and Greek mercenaries in Egypt, forged by William Eaton, an American diplomat, and Presley O'Bannon, a Marine Lieutenant, would prove decisive.

Led by a small detachment of Marines, the force of Christians and Muslims marched together for 45 days over 500 miles of desert before attacking and capturing the city of Derne. It was the first time the American flag was to be raised in victory on the far side of the Atlantic. After the action, Hamet Karamanli, one of the local leaders who had fought with the Marines, gave Lt O'Bannon a jewelled sword of the type that many of his Mameluke soldiers had wielded alongside their American allies. Today, when US Marine officers are commissioned they receive a sabre patterned on the Mameluke sword to honour the alliance and the victory, hailed by British Admiral Horatio Nelson as "the most daring act of the age."

It was also an act that was to define the mission of what was to become America's most famous fighting force, as celebrated in the words of the Marine hymn: "From the halls of Montezuma To the shores of Tripoli; We fight our country's battles In the air, on land, and sea; First to fight for right and freedom And to keep our honor clean; We are proud to claim the title Of United States Marine." A monument to those who died at Tripoli, at the United States Naval Academy, is the oldest naval monument in the country .

@Email:pgranfield@thenational.ae