In its commitment to "leave no stone unturned" in combatting Covid-19, the UAE is turning to a century-old treatment for viral disease that is showing promise with patients.

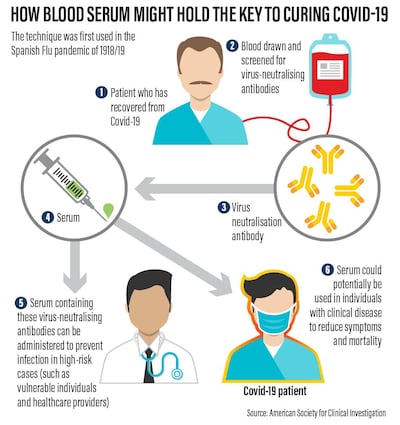

Known as Convalescent Plasma therapy, it involves taking virus-killing antibodies from the blood of people who have recovered from the disease and donating them to the critically ill.

With anti-virals still undergoing human trials and a vaccine at least a year away, CP therapy is being seen as a vital stopgap measure against the pandemic. A US Government-backed blood donation and distribution programme is already under way.

What is the evidence that it works?

Used during the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918/19, tests on hundreds of patients showed that giving critically ill patients transfusions of blood from those who had recovered could cut death-rates by half. The same approach was later used on other viral diseases, with similar results.

Studies conducted during the sars epidemic of 2003 and with a small number of Covid-19 patients suggest that, while not a guaranteed cure, CP therapy is safe and may boost the chances of survival.

What is the potential for CP therapy?

As the Covid-19 virus has spread around the world it has claimed more than 114,000 lives.

But over four times that number appear to have recovered and are thus potential donors of plasma – the component of blood that contains the antibodies that can defeat the virus.

UAE's covid-19 drive-through testing sites fully operational

However, the numbers of suitable donors is likely to be far lower. As with blood transfusions, all donations must first be screened to eliminate the risk of other diseases being passed on.

Donors must also have been symptom-free for at least 14 days, and test negative for the Covid-19 virus.

Because the recipients are already very sick, every effort is made to match the blood groups of the donor and patient, to minimise the danger of a reaction.

To have the best chance of being effective, the donated blood must also contain high concentrations of antibodies against the virus. Taken together, these requirements suggest that only a few per cent of donors may have blood suitable for use in CP therapy.

On April 12, medics at Sheikh Khalifa Medical City in Abu Dhabi announced that they were treating a patient with the plasma of an Emirati who had recovered from the virus

Dr Fatima Al Kaabi, head of haematology and oncology, said doctors were monitoring the patient, who has moderate to severe symptoms, to test the treatment’s effectiveness.

What other risks are there?

As Covid-19 was unknown just a few months ago, the studies now underway are also looking for signs of unexpected consequences of CP therapy.

These include antibody mediated enhancement of infection (ADE), where the donated antibodies make the infection worse.

Researchers also warn that the donated antibodies could alter the immune system of the patients, leaving them more at risk of re-infection.

What does donation involve?

Once the blood group, infection status and antibody concentration have been established, donors are connected to a so-called apheresis machine via a needle in one arm.

As the blood flows through it, the machine extracts the yellowish, antibody-rich plasma, while returning red and white blood cells back to the donor. The process takes around an hour or so.

The plasma – enough for several patients – is then chilled to minus 18C and either stored or dispatched to where it is needed.

Could it be used to protect health workers or the public?

Some advocates of CP therapy believe it could also help protect health workers from infection via so-called "passive immunity", in which a small dose of donated blood triggers the creation of virus-fighting antibodies, in a similar way to being vaccinated.

London left deserted by coronavirus lockdown

However, concerns about justifying the exposure of healthy people to the unknown risks and benefits of CP therapy have cast a shadow over its use.

Its more general use with the public is an even more distant reality.

What does the future hold for this treatment?

The studies now underway in the UAE will feed in to the global effort to assess the safety and efficacy of CP therapy.

But biotech companies are already looking to taking it to the next level.

An international alliance has been set up to mass-produce pure, concentrated hyperimmune immunoglobulins – the essential antibodies at the heart of CP therapy.

Plasma taken from suitable donors is first screened, treated to rid it of all viruses and purified with the antibodies within it concentrated to a standardised level.

This will speed the availability of CP therapy and make it far simpler to use in hospitals.

Robert Matthews is visiting professor of science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK