For five centuries the people of a much-coveted strategic Emirati town have been protected by a brooding stone and mud-brick hulk that seems as impenetrable as the soaring rocky blue peaks against which it is set.

Perched on a rise overlooking the remains of the tiny houses the original residents of the town lived in, the imposing structure looks as solid as the Hajjar Mountains nearby. In the early morning sun it is particularly impressive, its sand-coloured walls shining like a beacon. Fujairah Fort guards the entrance to Wadi Ham. Since about 1500 it has protected the people who lived in the tiny houses below from invaders from as far afield as Persia, Portugal, Holland and Britain. The leaders of these empires were all lured here by Fujairah's strategic position between the Gulf and the Indian Ocean.

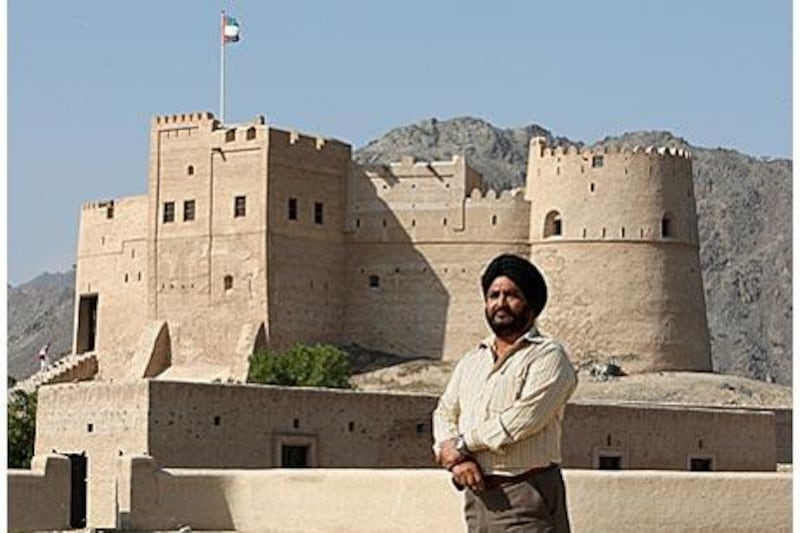

At different times, each tried to claim the emirate as its own. But the fort stands as testimony to Fujairah's strength and independence. To visitors, the fort appears as solid as the ground on which it is set. Amrik Plaha knows better. The engineer was part of a team that started to rebuild the fort from its ruins 12 years ago. He and the 56 workmen, five archaeologists, and one sheikh who were involved in the project are dedicated to reviving the history of his people.

Since 1997, the emirate has quietly undertaken the UAE's largest restoration project. As well as Fujairah Fort and the surrounding village, forts at Bithna, Awhala, Masafi and Dibba, the Al Hayl Palace and the Al Bidiya mosque have all benefited from the dedication and skill of Mr Plaha and his team. Al Bidiyan mosque opened to the public in 2003, and the sites at Awhala and al Hayl are open to visitors. Other buildings, such as Dibba and Masafi forts, are in the process of archeological investigation.

Fujairah Fort, once a crumbling building on the outskirts of the new Fujairah city, was the first project Mr Plaha embarked on. It and the houses that make up the Heritage Village it looks out over will open to the public next year. The fort was originally constructed at about the turn of the 14th century and first rebuilt in 1650 after attacks by Portuguese armed forces. Mr Plaha says his goal was to return the building to its precise former glory, free from the imaginative flourishes he sees on many restored monuments and that he "detests".

"This design is exactly like it was before," says Saeed al Samahi, the general manager of the Fujairah Tourism and Antiquities Authority. "We can show you the old photos of this fort. When we had no photos, we took guidance from the old people." Restoring the fort wasn't easy. "When I came here, it was a heap of debris," says Mr Plaha. "Cleaning took almost one year. This cleaning is done manually."

A team of archeologists works alongside Mr Plaha's crew in the initial stages of any restoration project he takes on. "For Fujairah Fort, because it was existing and standing, it was just to study the materials and date the buildings of the fort," says Dr Salah Hassan. "But in other buildings, like Masafi Fort or Dibba Fort, the buildings are only partly exposed and our archeologists work to uncover the base of the buildings."

At Fujairah Fort, archeologists discovered the remains of huge pots as well as tiny pottery vessels, some of which now sit in Dr Hassan's office. "The fort was used for administration and used by soldiers [as an observation post]," says Dr Hassan. "When there was a threat of war or even a threat from the climate, people came inside the fort." While the archeologists unearthed pottery, Mr Plaha's team began dismantling the high concrete-block walls of the fort where it faced the sea. The unsightly breeze blocks were put up following an attack in 1925, when British navy ships shelled the fort for 90 minutes after the late Sheikh Hamad bin Abdulla rejected an ultimatum from the then British political resident, Lt Col Prideaux.

"That was an incorrect restoration," says Mr Plaha, tutting. After the dirt and concrete were removed, work began to stabilise the mud-brick and stone building. To do so, Mr Plaha and his team decided to use modern techniques. "This mud is very good for the upper structure but not for the foundation because it has a tendency to suck in water. If we have modern technology, why not use it?" Mr Plaha's team strengthened the walls with thousands of micropiles. These are extremely strong steel pins that are drilled deep into the ground under a vulnerable building. It's a time-consuming process as each pile takes about two hours to put in. The entire process took months.

"Almost all the buildings [that comprise the fort] don't have foundations," says Mr Plaha. "We had to drill holes top to bottom through the existing structure to the solid earth." Next, the porous stone walls had to be filled. "The problem with the old stone walls is that the gaps are always there," says Mr Plaha. "To make it homogeneous we have machines filling the wall with cement. Then we complete the roofing."

Wherever possible, Mr Plaha used materials that were available to the fort's original builders. Sarooj, a type of clay from date plantations, was imported by the tonne from Oman to restore the fort's exterior. For the roofing, Mr Plaha used local palm-frond matting and had beams made of chandal wood imported from Africa, as it has been for centuries. Those three elements alone took almost two and a half years to complete, which is quick, says Mr Plaha.

"It's very fast. You know, restoration is [usually] a very slow process." But all the effort has paid off. Through the intricately carved wooden main door of the fort, the visitor enters a courtyard framed by four towers, three round and one square. Cool rooms, steep mud staircases and tiny peepholes that look out on to the Gulf below give a flavour of life for the bureaucrats and soldiers who once occupied the fort.

Hidden behind a small opening off one staircase is the huge former ammunitions room, its floor once covered with a thick layer of soft ash. In another room, gutters lead to a 12-inch hole. Under this was a large vessel that collected the syrup that ran off heavy stacks of dates that were stored there. To the side of this lies a deep, black pit where prisoners were once held. Climbing the thick steps to the second floor, visitors can enjoy the breeze and tranquillity of the majlis, or meeting rooms. Those who venture to the top of the fort will be rewarded with a stunning view of old and new Fujairah.

When Sheikh Hamad bin Mohammed, the ruler of Fujairah, came to see the project when it was first underway, Mr Plaha led him out on scaffolding to see the work first-hand. "Everyone was worried but he said, 'If people work on it, why can't I go?'" So impressed was Sheikh Hamad that he asked Mr Plaha and his team if they would stay to restore all of Fujairah's forts and the village below the Fujairah Fort where he once lived.

Nine years have passed and he has not looked back. "My team was called just to do this job but when the sheikh saw the fort he said, 'Amrik, you are not going back.'" The restoration of the 55-acre heritage village below is almost complete. It consists of 14 houses, including the house where Sheikh Hamad was born. "Two years ago he asked me, 'How far is the well from the palace?' I said, '25 or 30 metres'. He said, 'When I was a boy and my mother told me to get the water, it was very far from the palace!"

Sheikh Hamad regularly visits the site to monitor progress and relive old memories. Mr Plaha stresses that without his dedication, such a costly project would have been impossible. The sheikh's former home at the old village is one of three large, flat-roofed houses. Smaller houses, called kareen, are made with sarooj and have sloping, palm-frond roofs known as da'an, a feature unique to coastal Fujairah.

"There was also a market area and this was for crops and vegetables, herbs and also sheep, goats and medicine," says Dr Hassan. "We should consider that it was too difficult to get to Sharjah and Dubai at that time." Even reaching the village was no easy feat. Located halfway between the wadi and the coast, getting the goods to market from the nearest harbour still required a two-kilometre trek by donkey or on foot.

Older residents from Fujairah have also taken an interest. "People come and they tell me, 'This is my house,' and they are very happy to see their house restored," says Mr Plaha. Look, this is the town, this is the beauty of Fujairah," says Mr al Samahi. Several of the most beautiful forts are in fact found among the date gardens and tiny villages nestled in the surrounding wadis. They guarded strategic inland routes and the farmers who lived nearby.

The Bithnah Fort, for example, protected the main overland route from the interior to the Fujairah coast at Wadi Ham and surrounding farms and terraces. A single gunshot from one of the nine nearby watchtowers warned people of any impending danger. The fort also served as a jail and housed the guards. Archeaological finds show that people were settled at Bithnah at least 3,000 years ago. The more recent fort was built about 1735. In Wadi Hula, 30 minutes south of Fujairah city, stands the round tower of Awhala Fort, estimated to be 250 years old. It is built on the ruins of an Iron Age defensive structure that straddled the old trade routes between Oman and the north coast.

In the hills behind Fujairah city, Al Hayl Palace, believed to be about 90 years old, was the summer residence of the Sharqiyin royal family. There they relaxed in its courtyard and sheltered from the heat of summer in the cool of the wadi's fertile date gardens. And, of course, there is the famous Al Bidiya mosque, which dates from between about 1450 and 1600, according to experts. There are also the two ongoing projects in Masafi and Dibba. Two six-week excavations have already taken place at Masafi. Dibba is scheduled for a second season of excavation this winter, which will take two or three weeks.

The legacy of these people can be revived and remembered, says Mr Plaha. He believes the restored buildings can stand for another 500 years with proper care. For him, restoration is a vocation, one which is producing breathtaking results. "When you work from the heart, it comes," he says. azacharias@thenational.ae