Grey-haired, courteous and habitually sporting a benign smile, Brigadier General Qassem Suleimani looks more like a bank manager or high-school teacher than one of the Middle East's most feared and powerful spymasters.

He heads the Quds Force, the elite, external operations unit of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guards that has tentacles in Iraq, Lebanon, Gaza and Afghanistan. More recently, it has been accused of training Syrian forces to quell anti-government protests.

Mr Suleimani's success has come by meshing strategic diplomacy and black operations abroad, analysts say. But the Quds Force's hard-earned reputation for competence and sophistication is now challenged by US allegations it plotted a shambolic attempt to murder Saudi Arabia's ambassador in Washington using an Iranian-American second-hand car dealer and a Mexican drugs cartel.

The sensational charges, if proven, will also shatter the mystique surrounding Mr Suleimani, a spectral figure whom a US official, speaking to the London Guardian in July, compared to Keyser Soze, the pitiless and terrifying arch villain in the film The Usual Suspects.

Iranian leaders and officials have furiously denied any involvement in the alleged plot to assassinate Ambassador Adel Al Jubeir, also a senior adviser to King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia.

They have branded it a "comical" attempt by Washington to divert attention from the US's economic troubles and foreign policy failures in the Middle East.

A seemingly confident Iran yesterday called on the US to provide it with information about the purported plot. "We are ready to examine with patience any issue, even if it was fabricated," Iran's foreign minister, Ali Akbar Salehi, said.

Iran also has asked for consular access to the Iranian-American suspect, Manssor Arbabsiar, who is in US custody, accused of being at the centre of the alleged conspiracy.

Because of the operation's sloppiness, sceptics in the Middle East and the West have questioned whether it was really backed by senior figures in the Quds Force, as Washington claims.

It would be unprecedented for the covert unit to strike at a target on American soil: its stamping ground has mainly been in the region and its modus operandi has been to use trusted proxies. To solicit the help of Mexican gangsters would be another first.

But some security experts point out that intelligence services have made significant blunders before. In 2010, the Israeli Mossad was accused of sending a hit squad to assassinate a Hamas official in a Dubai hotel. To Israel's acute embarrassment, the suspected operatives were caught on videotape following Mahmoud Al Mabhouh in the hotel and photos of them were distributed to the media by Dubai Police.

Like all spymasters, Mr Suleimani, 54, likes to remain in the shadows. But he famously broke cover early in 2008 by sending a goading text message to the then commander of US forces in Iraq, David Petraeus, now the director of the CIA.

The Iranian argued they were equals because he controlled Iran's policy towards Iraq, Lebanon, Gaza and Afghanistan. Mr Suleimani had just helped broker a vital truce in Basra between US-backed Iraqi government forces and those of the radical Shiite cleric, Muqtada Al Sadr. Gen Petraeus related this anecdote last year in an address at the Institute for the Study of War, a Washington-based think tank, to illustrate the difficulties of dealing with Iran.

Traditionally, he said, diplomacy involved dealing with another country's ministry of foreign affairs. But in Iran's case, it meant dealing with a "security apparatus". Mr Suleimani is "the most powerful man in Iraq without question", according to Iraq's former national security minister, Mowaffak Al Rubaie. "Nothing gets done without him," he told the pan-Arab newspaper Al-Sharq al-Awsat last year.

The Quds Force - its name is the Arab word for Jerusalem - was established after the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, during which Mr Suleimani distinguished himself in combat, rising rapidly in the ranks of the Revolutionary Guards.

He reportedly headed covert operations in Bosnia during the Balkan wars of the 1990s and was appointed head of the Quds Force in 2002, just months before the US-led invasion of Iraq.

The special unit is directly answerable to Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and is thought to number anywhere between 5,000 and 15,000 troops. The Quds Force replaced Iran's Office of Liberation Movements, which was formed directly after the 1979 Islamic revolution to help radical groups in the Middle East, most notably Lebanon's Hizbollah militia.

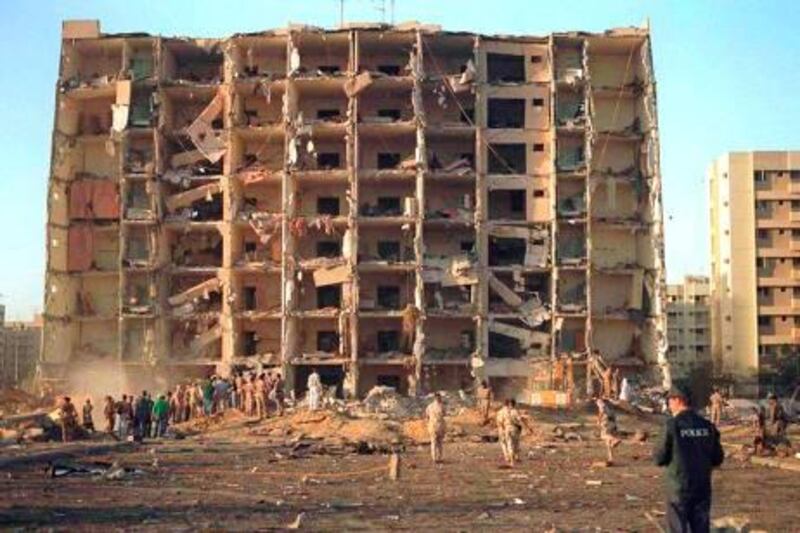

The force is accused of plotting the 1994 bombing of a Jewish cultural centre in Argentina that killed 85 people. Washington, meanwhile, blames the Quds Force for some of the worst terrorist acts against US troops overseas, including the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia that killed 19 American military personnel. Tehran has denied any involvement in both attacks.

More recently, US officials charge that the Iranian group has smuggled rockets into Iraq for use by Shiite militant groups, including an attack on Camp Victory outside Baghdad on June 6 that killed six US servicemen.

The veracity of the assassination plot matters little to Iran's Gulf Arab rivals, Gerald Butt, editor of MENA Prospect, a new London-based weekly focusing on political risk, said in an interview. "Given their concern about instability from their own Shiite communities and Iran seeking to bolster its influence in Syria and elsewhere, the battle lines are already drawn."

[ mtheodoulou@thenational.ae ]

Faisal Al Yafai's comment and Shadi Ghanim's cartoon, page a18