Somewhere in the world a community is facing catastrophe. They have no food and no means to cook it. Malnutrition and death are just days away.

In these circumstances, lives may hang on a simple packet of biscuits.

High energy biscuits to be exact, packed with energy and micro-nutrients. Each packet is enough to feed a person for one day.

This week saw the announcement that Princess Haya bint Al Hussein contributed to a new fund to allow the rapid purchase of stocks of the biscuits, to be managed by the UN World Food Programme.

The gesture by the wife of Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid, Vice President of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai, was described as “a life saver” by David Beasley, the executive director of the WFP, who called the princess “a true champion for people facing hunger and poverty".

___________

Read more:

[ Princess Haya launches special fund to send food to disaster zones ]

[ Dubai aid air-drop will help 500,000 Rohingya refugees ]

___________

To the layman's eye, the biscuits look unexceptional and not particularly enticing.

But that’s not the point, says Stefano Peveri, a senior logistic officer at the WFP and the UN Humanitarian Response Depot Dubai manager.

“They’re not as tasty as you would buy in the supermarket,” he says.

“But they are very nutritious and packed with micronutrients.”

The formula has changed over the years. The first biscuits were designed to provide a high energy boost and could be kept for up to two years.

The current recipe delivers a more sophisticated package, but has a shelf life of just 12 months.

The WFP is working to make this longer, says Mr Peveri.

Manufacturing takes place at a number of approved centres around the world. The closest factory to the UAE is in Oman, but owned by a Sharjah company.

The biscuits are kept in 100-gram foil packets and stored in a Dubai warehouse. The current stock is a 150 metric tonnes – or enough for 1.5 million people.

What happens next is dependent on rapid response.

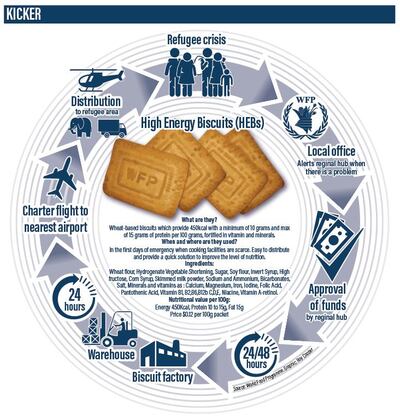

Often the first sign of trouble is spotted by a local or country office of the WFP. It could be a natural disaster, like a famine or drought, or a refugee crisis provoked by persecution or conflict.

In recent years, the WFP has supported Muslim Rohingya refugees fleeing to Bangladesh and displaced rural populations flocking to the Somalian capital Mogadishu looking for food.

Supplies were also sent to the Philippines in 2013 after Typhoon Haiyan, and Afghanistan in 2014.

In 2016, the WFP bought 2.6 million tonnes of food worth US41.36 billion and delivered 3.5 million tonnes of food to 74 countries.

In the same year, Humanitarian Response Depots, like the one in Dubai, sent out more than 87,000 tonnes to 12 countries on behalf of 170 organisations.

The biscuits are usually the only food source in the first instance, says Mr Peveri. The dire circumstances of those in need often mean they have no means of cooking:

“So there is no point in giving them beans or wheat," he says.

The biscuits, he explains, are only intended as a stop gap “for three or four days” until more long term support can be brought in with other agencies.

They can be particularly useful for refugees still on the move.

“We can supply them half way and give them a vital boost of energy," Mr Peveri says.

Once a local office has identified a problem, the regional hubs, such as Dubai, are contacted. Flights are then chartered and supplies of the biscuits sent to the most local airport to the affected population.

From here, the biscuits are loaded on to lorries or helicopters.

“But we have also used elephants and camels”, says Mr Peveri. “Whatever works best.”

Speed is obviously of the essence. The WFP aims to have the assessment of needs and the funds made available for transport within 24 to 48 hours of being alerted.

A similar time period applies to delivering supplies to those most a need. “Not only do you need to have the biscuits available in places like Dubai, you need to be able to move them fast,” says Mr Peveri.

“I believe in this project, big time,” he says. “It saves lives.”