As India's discussion of the Mumbai attacks begins to drift into pop culture, Aman Sethi scans the nation's comic book stands, where make-believe heroes take cues from the hawkish political right. The first anniversary of the November 26 terror attacks in Mumbai was marked in India by a deluge of news programmes, special remembrance features and radio talk shows. On television screens and editorial pages, the previous November's itching desire to "teach Pakistan a lesson" - exemplified by the fading Bollywood actress Simi Garewal's public call to carpet-bomb the place - seemed to have been replaced by a more inwardly-directed call to "learn lessons". Shunning explicit calls to war, pundits instead mulled the need for increased military expenditure, national identity cards and increased public surveillance.

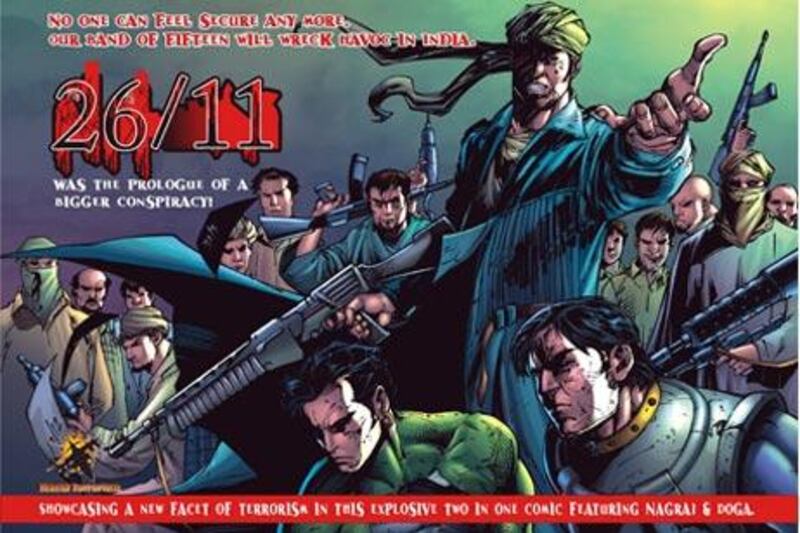

The inevitable outpouring of mainstream "26/11" cultural production has yet to occur (although the Bollywood director Ram Gopal Verma surveyed the Taj Hotel's burnt shell for material for his next film), but the first signs are showing up - in comics. In November, Raj Comics published 26/11, a fantastical re-imagining of the three days during which 10 gunmen stormed two five-star hotels and the Chhatrapati Shivaji train station, killing 166 people in the process. Though Raj Comics does not publish circulation figures, the comics they publish are probably among the most widely read comic books in India. In an interview with Tehelka magazine, Sanjay Gupta, Raj's founder and studio director, estimated their circulation at about 70,000 copies per standard issue.

Scripted in street Hindi, with the action laid out in busy, multi-frame pages, each Raj Comics instalment features one of a cast of a nine primary characters - including the half-man, half-snake Nagraj and the brawny, dog-mask wearing vigilante Doga - tackling challenges ripped from the headlines. Recent Raj plots recount the discovery of nine dead children in the house of an upper-middle class family in a Delhi suburb; a scandal involving the sale of contaminated blood to hospitals; and even the fate of an imaginary winner of Indian Idol.

In 26/11, the real-life Mumbai attacks are only a precursor to an international plot involving Russian arms dealers, Somali pirates, and a fictitious Pakistani terror group, the Lashkar e Aaka, that is determined to hijack the INS Viraat, India's sole aircraft carrier. Nagraj and Doga clear the city's besieged hotels with relative ease, only to discover an unholy international criminal nexus that threatens to destroy all of its residents.

Despite having sold over 100,000 copies, 26/11 has been trashed by Raj's dedicated fan-base, whose members congregate on active online message boards hosted by the publishers. Fans discuss the nuances of each issue, present page-by-page critiques of the action, and make broader observations on themes and plots. The consensus online was that, in 26/11, Raj's heroes were simply not heroic enough, their success not as sweeping, triumphant and pure as it could - and should - have been.

"In this comic, Nagraj and Doga get beaten more than they have in any other comic," wrote pbuster, a fan on the "26/11 review board", referencing sections where Nagraj and Doga take a few lumps from what appear to be genetically-enhanced jihadis. "There are some scenes which really make fools of our heroes." Satvabodh, a fan who gave the plot of 26/11 a two out of five, wrote: "Usually, reading such a comic should make one's blood boil and this comic should have been a tribute to 26/11. But neither did I feel any pain, nor did they mention a single 26/11 martyr!"

Other readers complained that the plot failed to justify the need for two of the world's greatest superheroes to do what amounted to human police work. Nagraj and Doga let too many innocents die, and in the end only returned matters to their status quo. Where was the transformative power of the superhero? Raj seems to have received the message. In December, they launched a new title, Halla Bol (literally "Raise Mayhem"). In it, Nagraj and Doga cross into Pakistan to raze 10 terrorist training camps to the ground.

While Raj Comics gesture towards the potential of vigilante-style justice, Indian War Comics, a 14-month old series distributed by Om Books, look back in history to laud the past exploits of the Indian Army. The first issue, Yeh Dil Maange More ("This heart wants more"), published in November 2008, celebrates the life and martyrdom of Captain Vikram Batra in, who died during the the 1999 Kargil War with Pakistan. The second issue, published in November 2009, lauds the exploits of Colonel NJ Nair in conflicts in India's north eastern states. "The point," according to Aditya Bakshi, the books' author, in an interview with the Times Online, "is to increase the visibility of the army and promote the ethics of patriotism, self-sacrifice, and honour." As in 26/11 and Halla Bol, the notional "lessons" are many, but wisdom is in short supply.

In 1999, Rahul Bedi, then the India correspondent for Jane's Defence Weekly, contributed an essay to a collection called Guns and Yellow Roses, in which he described the Kargil war as follows: "Nearly 1,200 men, including 487 Indian soldiers, died. Another 1,100 Indian soldiers were maimed, half of them permanently. "Senior commanders initially portrayed the intrusion as an infiltration by a 'handful of foreign mercenaries' ... and issued orders for them to be dealt with accordingly. This, in turn, lead to panicky officers dispatching ill-equipped, unacclimatised troops on 'suicide missions' up sheer mountain slopes."

Yeh Dil Maange More gives little sense of this terrifying confusion, thanks to its simple script ("This is the story of the bravest of India's brave"), unimaginative layout and poor craftsmanship. One must rely on a close comparative analysis of the characters' beards just to tell them apart: Batra's is wispy with a rounded chin, his commanding officer sports a manly stubble, and the Pakistani intruders have pointy things stuck beneath devious smiles. In page after page of neatly boxed, rectangular panels, Batra leads his men through acres of empty whitespace on a mission to capture Point 4875 before dawn breaks.

Does the young, soon-to-be-engaged captain experience one moment of doubt? Weakness? Love? If he does, we hear little about it. "Yes it is raining bullets and perhaps we die. But what more worthy death can one hope for?" Batra observes as he guides his troops up a vertical rock face. "This is what we dreamed of ... to die a soldier's death and live forever." Contrast this with Sankarshan Thakur's "Journeys Without Maps", another essay from Guns and Yellow Roses. "'What drives you?' I once asked a Rajputana Rifles soldier ... He lookedat me incredulously and said: 'Orders. If we don't follow orders, what will our families eat?' I wondered about big words like patriotism and bravery and the soldier said: 'I don't know about that. Perhaps sometimes, when your fellow soldiers die, there is too much anger. It is then a blinding madness ...'"

If either Raj Comics or Indian War Comics explored this space of blindness, they might give us some sense of what it means - how it feels - for individuals to go to war for their states. For evidence of this, we need look no further than Parismita Singh's The Hotel at the End of the World, an extraordinary graphic novel published in early 2009. It uses the same "commando comics" aesthetic as Indian War Comics, but tells a very different story about armed conflict.

Singh writes of the ghost of a Japanese soldier from the Second World War who haunts the hills of Nagaland and Manipur, along the Indo-Burmese border. There are no exits for Singh's warrior, no luxury of a glorious charge into the enemy's blazing guns. In her exquisitely rendered frames, there is only the monotonous terror of a wet rainforest, the drudgery of hunger and fatigue, and a long slow march to the end.

"He fought and fought through whole ages, though in his zeal it seemed to him mere moments." The Second World War ends, decades pass; one day he stops walking and wonders where he is, who is firing the bullets that whizz past him. "Where was the war? Where was his regiment? There were other battles, he could see. But this was not his war ..." As the ghost looks on, war continues in an interminable loop with new sets of friends and foes; the colonial forces of the Second World War blend into Indian paramilitary forces conducting counterinsurgency operations. Graveyards pile up.

Read together, these comics offer three dimensions of the Indian warrior: the superhero, the soldier and the unremembered ghost. Nagraj and Doga embody the aggressive fantasies of a frightened nation; soldiers like Captain Batra are flattened into myths in service of those same fantasies; but only ghosts know the true price of war. At the end of Singh's book, her ghost soldier is roaming the mountains of Manipur, stopping occasionally for a drink at the hotel at the end of the world, alone save for the company of that establishment's manager. We can only hope that one day he might be joined there by the soldiers of the Kargil war, a shape-shifting snake, and a muscle-bound man in a purple dog mask.

Aman Sethi is a Delhi-based journalist for The Hindustan Times.