Bundelkhand in south-east Uttar Pradesh is among the most underdeveloped and poverty-stricken areas in India. Crime and government corruption are rampant. The upper-caste people rule by the strength of their money and influence. The poor, lower-caste people are daily wage labourers or work as farmers in the fields owned by the elite.

The situation for women in Bundelkhand is even worse. To prevent free mixing with boys, residents do not send their girls to school. Girls are generally married off at an early age. There are many instances in which in-laws torture and even burn young girls if the parents cannot satisfy them materially after marriage, even though the dowry has been paid. Abandoning a girl after a few years of marriage is also common here, as most of the marriages are not registered in the civil court. Domestic violence is prevalent. Most of the rape and sexual abuse cases are not reported to the police for fear of social stigma, and hence the rates are high.

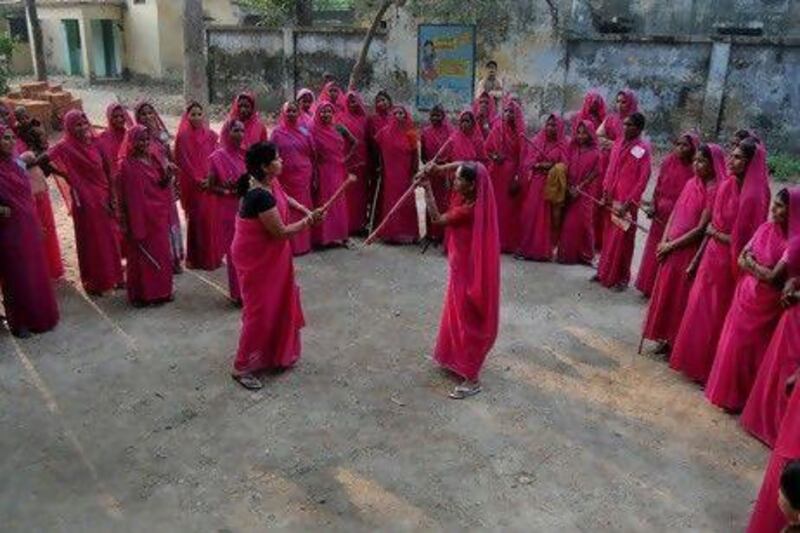

Sampat Pal Devi, 48 and a mother of five, has emerged as a voice for these women. She got together with a group of like-minded women from the area and they christened themselves the "Gulabi Gang". They quickly became popular for their "gulabi" (pink) saris - pink is an "independent" colour in India, not aligned, as are other colours, with a particular political party - and for their fierce ways of solving problems and helping each other.

The gang came into prominence in 2007, when they beat up the then-officer in charge of the police station in the nearby town of Attara. The incident happened when Devi and her group intervened in a matter on request from a lower-caste woman whose husband was kept in police custody for 13 days without charges. Devi demanded the officer register a case or release the man. When the officer abused her verbally, Devi says, she flared up and slapped him, and the other Gulabi Gang members then beat him. The officer was eventually suspended on disciplinary grounds.

The incident drew media attention and ignited a debate over the use of violence to solve problems. The gang was noticed by government and local officials, and their reputation grew. The group that began with a few members now boasts 300,000 in the state of Uttar Pradesh alone.

Nowadays, they not only deal with people's personal problems but also intervene in public matters.

They first try to solve a problem in a non-violent manner, and if that doesn't work they resort to other methods. In cases of corruptor irresponsible government officials, gang members may shame them in public, threaten them or beat them up. According to Devi, physical violence has proved the most effective solution, although she now says it has mostly become unnecessary.

"My father was a poor cattle breeder from the lower caste," says Devi. "During my childhood I was never allowed to study, whereas my brothers used to go to school. I heard from my parents that education is for boys and that girls should learn to manage the household. This distinction never made me happy."

We are sitting in her single-room home and office in Banda, a dusty, noisy and dirty district town with a big market area and the rail hub of the region. Looking at Devi's soft face charged with emotion it is difficult to believe that she strikes fear in the hearts of hooligans, corrupt officials and other men most women would be terrified of confronting.

"As my father was poor and could not afford a fat dowry, they married me off to a widower who was 13 years older than me, but was a nice man," she says. "He was always there beside me during the violent period of my life, when I used to get death threats from people against whom I was fighting for justice. He is old now and stays with my other family members in Attara.

"From the beginning of my marriage I had problems with my in-laws, as I was a bit unconventional for them. I used to mix with all the women in our village, including those from the lower castes. I never believed in the caste system; rather, I believed in humanity and equality.

"One day after a fight with my in-laws my husband and I left our village house for good and started staying in a small rented place in Attara, which is a small town near our village. It was a very hard time - my husband set up a small tea shop at the bus stop and I used to help him after I was done with my household chores.

"The neglect and oppression that I got from my family as a girl and from my in-laws as a woman triggered my wish to help women like me. In the beginning it was tough to convince the tortured and deprived women to retaliate, but slowly they started understanding me and supporting my vision.

'After I built up a big group we started intervening in the family affairs of others on request. We used to go together to solve the cases. In the start only women affected by domestic violence used to come; now I solve everything from disputes over land to child marriages. Men, too, come with their problems. Now I am matured and always try to stick to the law. Now we do not have to use violence. Our name and that we are coming is enough to scare away the bad guys."

I join Devi for a drive to Fatehpur, about 50km from Banda, for a Gulabi Gang meeting.

As we approachthe town we see women in pink saris, some of them carrying batons, moving in groups towards the campus of the district magistrate's office, where the meeting will be held. Once we arrive, Devi moves confidently through the crowd towards the dais. She then speaks, without notes, in her trademark raspy voice to the rapt audience about the poor, lower-caste people of Bundelkhand and their fight for justice.

And while the sometimes violent approach of Devi and her gang may be controversial, their efforts do seem to have tamed the badlands of Bundelkhand to an appreciable extent, and are certain to continue. The Gulabi Gang is fast spreading out of Uttar Pradesh to other states, and last year ran an independent candidate in the state municipal elections of Madhya Pradesh against the high-caste nominees of the national political parties. Though they lost the elections, they gained even more media attention and support from the poor and lower-caste people.

Pink power rolls on.