NEW YORK // The allegations describe the most heinous crimes imaginable: children drugged and forced to commit cannibalism, soldiers hacking off the limbs of women and children and an 11-year civil war funded by the sale of diamonds.

But the three-year-old trial of Liberia's former president, Charles Taylor, for supplying arms to rebels in neighbouring Sierra Leone came to the world's attention only when model Naomi Campbell and actress Mia Farrow were called to testify about a gift of uncut diamonds. Mr Taylor is being tried by the Special Court of Sierra Leone. Most of the proceedings are taking place in that country. However, Mr Taylor is being held in the Netherlands and the celebrities testified there at The Hague.

Advocates of war-crimes tribunals lament what they call the "depressing" fact that their battle to secure justice against the masterminds of crimes in places such as Sierra Leone, Rwanda and the Balkans fail to get the exposure they deserve. "It is somewhat disappointing that it takes Hollywood actresses and models going to a party with a former dictator, who is reported to have given a conflict diamond to a model, to get the media's interest in this important development," said William Pace, of the Coalition for an International Criminal Court (ICC).

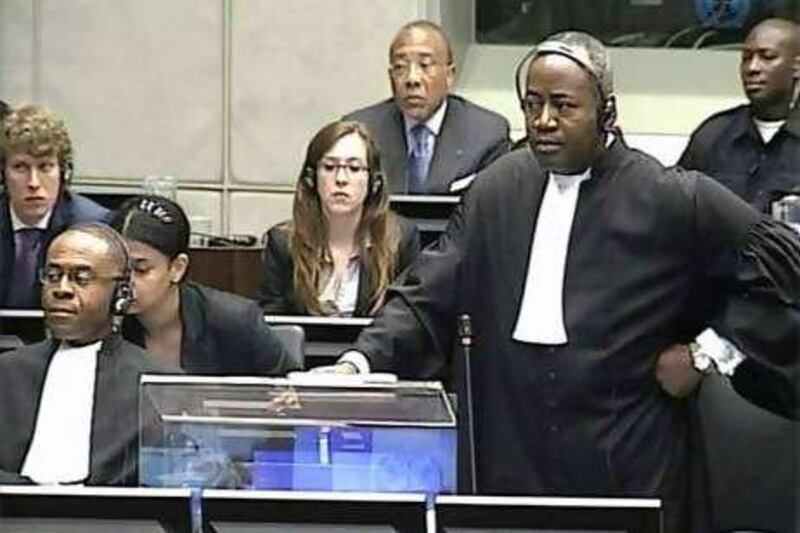

Mr Taylor's trial at the International Criminal Court in The Hague continues this week after testimony by the two celebrities during the last two weeks. The idea of establishing war-crime tribunals was proposed after the First World War to try Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II. But they did not become reality until after the Second World War, when 22 German and 25 Japanese leaders were convicted in trials in Nuremberg and Tokyo.

Efforts towards war-crimes accountability dwindled during the Cold War, and it was not until after civilian massacres in the Balkans conflict and Rwanda's genocide of 1994 that the world community agreed to establish new international tribunals. Since then, business has boomed, with UN-backed special tribunals for Sierra Leone, Cambodia, East Timor and Lebanon, and a permanent body, the ICC, pursuing violators in Uganda, the Central African Republic, Sudan and Congo.

However, tribunals for war atrocities have not captured the public imagination, said Christopher Hall, a lawyer for Amnesty International. "These crimes have not really been seen as crimes, but political and diplomatic events to be solved by diplomats and politicians," Mr Hall said. "Almost every single one of those prosecuted in international criminal courts has been responsible for horrors that would otherwise have seen them characterised as murderers and serial killers. But for some reason, the stories have never been pitched that way."

He believes that the charges against Mr Taylor and other indictees, such as Joseph Kony of the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), who created a child-soldier army that has terrorised northern Uganda and several other nations in Central Africa, are simply "too big" to grasp. Under Mr Kony's leadership, the LRA has abducted more than 24,000 children into its army and continues to wage a campaign of murder, rape and looting that has displaced about two million people.

"The numbers of victims is sometimes incomprehensible as are the types of crimes, like those committed in Sierra Leone, with child soldiers, amputations and rapes - it's just beyond people's comprehension," Mr Hall said. Advocates for the system of international tribunals complain that a review conference in June for the Rome Statute, the treaty that set up the ICC, received "almost no coverage at all in the world's media", said Mr Pace.

International war-crimes tribunals will not be taken seriously until they shake off the criticism that they serve the interests of history's victors, said Richard Dicker, a legal expert for Human Rights Watch. "There is a real uneasiness in the international justice landscape that those who appear before tribunals are much more likely to be officials or heads of weaker governments from the global South, as opposed to those from among the permanent members of the Security Council," Mr Dicker said.

"This is an unfortunate and ugly reality and weakness in what is an emerging system. "And this unevenness has to be fixed in order for this emerging system to retain its credibility and legitimacy." jreinl@thenational.ae