Like most dictators, Hosni Mubarak gave officials free rein to name anything after him and his wife Suzanne - schools, hospitals, roads, squares, libraries and subway stations. By the time he was forced out of office in February after 29 years in power, Egypt had hundreds, perhaps thousands, of facilities and institutions named after him.

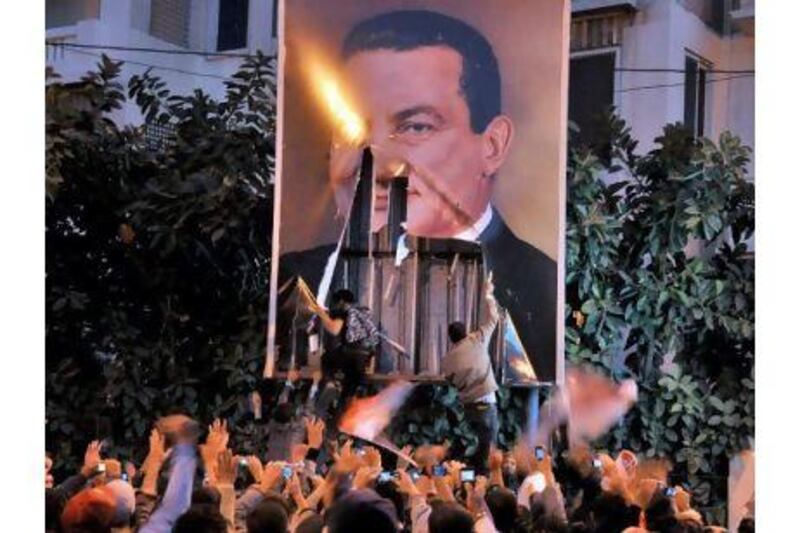

During the 18-day uprising that led to Mr Mubarak's removal, millions of protesters across Egypt took out their emotions on many of the giant billboard posters of the 82-year-old leader. Images were torn up, defaced or pelted with shoes - a popular gesture of contempt in the Arab world since an Iraqi journalist threw his shoes at the then US president George W Bush in Baghdad in 2008.

Even so, most of the large signs bearing Mr Mubarak's name or that of his wife remained largely untouched. Perhaps they would have taken too much time to remove, or maybe everyone out protesting was busy doing something else. Possibly there was fear of violence by Mubarak supporters.

That all changed with a court verdict on April 21, when a judge ruled that the name of Mr Mubarak and his wife must be removed from all public facilities and institutions.

Predictably, authorities were slow to implement the ruling. The verdict ordered Prime Minister Essam Sharaf to remove the Mubaraks' names, but ordinary Egyptians took the job upon themselves. Within hours, the name of Mr Mubarak and his wife were nowhere to be seen in this country of more than 80 million people. Many were replaced by makeshift signs bearing new names associated with the uprising.

It was a symbolic but significant step in the dismantling of Mr Mubarak's legacy. His reputation was further tarnished when he and his two sons were detained over corruption allegations. Mr Mubarak and one of the sons, one-time heir apparent Gamal, have also been questioned over the killing of protesters. Suzanne Mubarak is being investigated for corruption and her two daughters-in-law have been questioned by prosecutors about the sources of their wealth.

In an intensely publicised citation for his ruling, the judge Mohammed Hassan Omar said naming facilities and institutions after Mr Mubarak and his wife did not have legal basis. "It was done by officials seeking the backing of their superiors and for other reasons too despicable to be mentioned," Mr Omar said.

To allow the display of the Mubaraks' names to continue, said the judge, would be a provocation to the families of the nearly 850 people killed in the uprising. Removing their names, he continued, would help protect the places from attack by Egyptians hurt by the regime over the years.

This week, the company that runs Cairo's subway renamed the network's largest station at the bustling Ramsis Square to "Al-Shohadaa," or "The Martyrs," in tribute to the slain protesters. The choice of the new name followed a survey on the company's Facebook page in which more than 30,000 people took part.

The story of the proliferation of the Mubarak name speaks of how the former air force commander and war hero had transformed from a humble and pragmatic leader in the early years of his rule to the authoritarian ruler at the end.

Soon after he came to power in 1981, following the assassination of his predecessor Anwar Sadat by Islamic militants, Mr Mubarak, perhaps out of modesty, publicly stated that he did not want to follow the widespread custom in the region of having his name planted on public institutions.

Similarly, he also stated in the early 1980s that he would not seek a second term in office, arguing that ruling Egypt was a heavy burden. But by the time he stepped down in February, he had served five terms in office, ran the country much like a personal fiefdom and many of the country's high profile projects were named after him.

Suzanne, who had been a major source of behind-the-scenes influence, also kept a low profile during the early years, partly because the liberal attitudes and high profile assumed by Mr Sadat's wife Jihan did not appeal to many in a mainly Muslim and conservative Egypt.

Yet Suzanne soon became highly visible through her involvement in humanitarian and educational projects. She came to be widely believed to have been the driving force behind efforts to ensure Gamal's succession of his father, a prospect that most Egyptians as well as the military objected to. Gamal's possible succession was one of the key motives for the youth groups that organised the revolt.

Naming facilities after serving leaders as well as the public display of their image are a time-honoured political tradition in most parts of the Arab world. Though largely symbolic, tearing signs bearing their names or defacing their images often signal the beginning of the end of their regimes.

Portraits of Colonel Muammar Qaddafi of Libya's have been torn down or defaced by protesters in at least three Tripoli neighbourhoods.

Amateur footage of protesters tearing down a giant portrait of Syria's president, Bashar al Assad, in a small Syrian town in the early days of the nearly two-month revolt in that nation will most likely be remembered as the moment when Syrians decided they had had enough of the eye doctor who succeeded his father as president in 2000.

Like Mr Mubarak, Mr al Assad had let it be known when he first took office that he did not want his portraits to be displayed everywhere like his father's before him or for state institutions to be named after him. But again, smiling or waving images of Mr al Assad soon began to proliferate and now match or exceed those of his late father, who ruled Syria for some 30 years.

In Iraq, members of the Shiite majority took it upon themselves after Saddam's ouster to rename bridges, roads and even entire neighbourhoods in Baghdad and elsewhere after Shiite saints or clerics who fell victim to the regime.