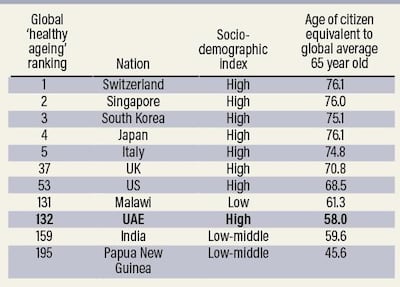

We all want to age well, and now we know who does it best. The first global study of its kind revealed the Swiss have the lowest rate of age-related health problems, with citizens of Singapore, South Korea and Japan not far behind.

The study shows the inhabitants of Papua New Guinea are at the opposite end of the scale, with the average 46-year-old living in the country suffering from health problems that are typical of the global average 65-year-old.

By contrast, the average Swiss does not reach that level of health until they are 76.

The study's league table of 195 nations was published this month in The Lancet Public Health and holds few surprises.

By and large, rich nations appear higher up the table than poorer countries.

But there are some exceptions, such as the UAE, which is ranked 132nd despite being among the top 10 wealthiest nations per capita.

On average, people in their late 50s living in the UAE can expect to have the health problems of a typical 65 year old.

The study, led by Dr Angela Chang of the Centre for Health Trends and Forecasts at the University of Washington, is a reminder of the public health concerns facing residents of the UAE.

Rising cancer rates and respiratory disorders are among the biggest concerns in the Emirates, as is cardiovascular disease, which can lead to strokes and heart attacks.

CVD alone accounts for about 30 per cent of all deaths in the UAE, with efforts ongoing across the country to tackle the problem, including campaigns to promote more exercise and a better diet.

Yet the biggest challenge is getting people to take those campaigns seriously.

That problem is not helped by the way in which even health experts seem to change their advice regularly.

From how best to measure obesity — BMI or waist circumference — to whether a specific food is healthy or not, a healthy lifestyle often appears to be open to interpretation.

For example, eggs were regarded as an unhealthy source of cholesterol, an "artery-clogging" substance linked to CVD, and official advice during the 1980s led to a decline in egg consumption across many countries, including the UAE, which experienced a 70 per cent drop.

But researchers began to raise doubts about the role of eggs in increasing cholesterol levels and the health advice soon changed, with experts blaming "incorrect conclusions" based on "early research".

Other than those eggs with a genetic propensity to high cholesterol, they were cleared to be put back on the menu.

That could be about to change again after researchers in the US this month published a study of the link between the diet of almost 30,000 people and their risk of CVD up to 30 years later.

Published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the findings showed the consumption of foods that are rich in cholesterol, including eggs, resulted in a higher risk of CVD, a risk that increases the more you eat.

For most people, the risk isn't huge — it is less than a 10 per cent increase for those eating a few eggs per week, rising to 27 per cent higher for people who eat two eggs a day.

Even so, the results of the study should be taken into account when the current dietary advice is updated.

However, judging by their reaction to the findings of the study, few experts expect to see a knee-jerk reaction towards eating eggs.

While they once would have been quick to wag their fingers at a gluttonous public, they have now stressed the limitations of the research, limitations that have always existed.

Firstly, such cohort studies can never definitively prove a link exists between CVD and the amount of eggs you eat.

There could be other factors that affect people who eat lots of eggs, driving up their risk of serious health problems and creating the illusion that eggs are to blame.

Another problem is that the cholesterol intake of those involved in the study was established only once — in many cases, decades before they developed CVD.

The researchers cannot say for certain if the people in the study stuck rigidly to their habits in the interim.

Finally, the study was conducted on people living in the US, with their own diet and lifestyle.

As such, extrapolating the findings beyond America, or even beyond the people in the study, is problematic.

With even large nutrition studies proving less than compelling, researchers are now looking at other approaches to explain health risks.

Studies that focus on how individuals respond to what they eat are among the most popular of these efforts.

The simplest, in principle at least, are so-called "N-of-1" studies. Rather than looking at potentially meaningless averages, these studies assess results from individuals, whose characteristics are monitored as their diet is changed.

While N-of-1 studies are still in their infancy, they have produced impressive results.

In a pioneering 2015 study in Israel, 800 people were monitored as they ate meals, with the results showing radically different responses to identical foods. The researchers then devised an algorithm to predict how each person would respond to a specific meal.

That allowed the researchers to tailor diets that tests showed led to healthier responses for each person.

While these results were promising, such trials are demanding and expensive. They also require a radical rethink of how scientists determine what methods work.

But with the World Health Organisation saying that poor diet is killing more people than starvation, the time for radical thinking is now.

Robert Matthews is a visiting professor of science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK