“I am a man who, taken alive, would have to be dragged in chains behind the meanest camel in the herd.”

Strong words. Yet Antara ibn Shaddad was no average warrior-poet. To many, he is the warrior-poet.

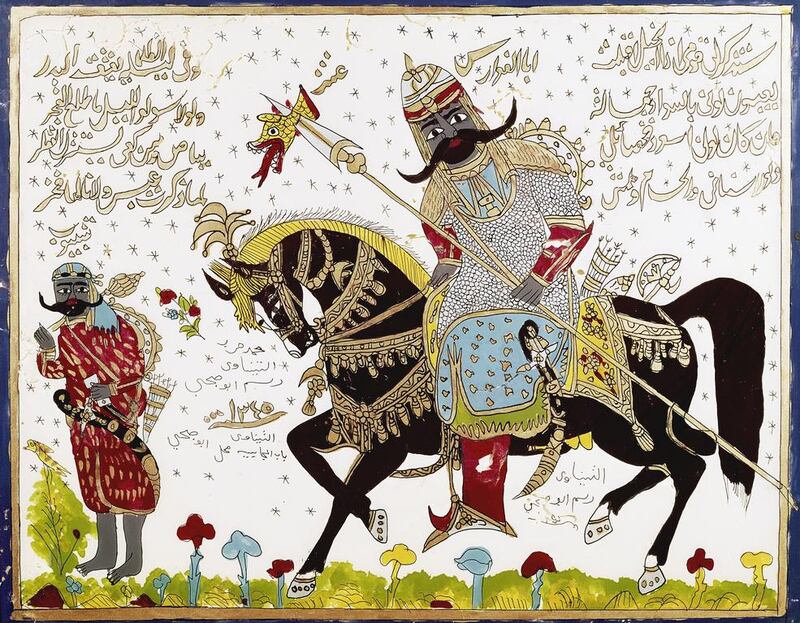

The son of Shaddad of the Banu Abs and an Abyssinian slave mother, Antara rose above prejudice and shook off the shackles of his birth, leaving legend in his wake.

He was the fiercest among his peers and one of the most articulate. His poetry is included among the Mu'allaqat, the seven most-admired poems said to have been hung inside the Kaaba in Mecca.

Also known as Antar, “the valiant one”, he was the subject of two lectures in Abu Dhabi and Dubai last week moderated by James Montgomery, the Sir Thomas Adams’ professor of Arabic at University of Cambridge.

“The Library of Arabic Literature is a research project funded by the New York University Abu Dhabi Institute, and the mission is to produce editions of works of old Arabic, and to translate them into modern, lucid English in a contemporary idiom,” Prof Montgomery says.

He began working on a book of Antara’s poems five years ago, and believes there are just two to go.

“The 12 lines of English that you see on this page here took me six weeks of work, and it took me something like seven or eight different attempts to achieve the point at which I felt happy and satisfied. Because at the end what you’re trying to translate is not the words, but the experience,” Prof Montgomery says.

“I grew up in Scotland, I’m a Glaswegian. I don’t mean that I’m sort of a Bedouin who lives in the desert in any sense.

“But my experience reading this poem, based on the training and the education and everything else that I’ve had, is what I want to communicate in English, as a way of getting back to the Arabic original.”

Such translations can often help to explain more obscure Arabic to those who do not understand it naturally or easily. But while the language is rich, the world in which the poems reside is “very simple”, Prof Montgomery says.

“The dominant force in the universe is time, time that is also synonymous with fate and with death. In addition to that, you have man, and man is associated with a unit – be it the family, the tribe, the clan or the band of warriors.

“And the setting of this is the desert. So out of that very simple matrix, you get a lot of complex poetry.”

The poems cover a broad range of scenarios, painting different pictures of pre-Islamic warrior life. One laments the death of one of the tribe’s heroes during a 40-year war that began with a horse race. Others boast of repelling a surprise dawn attack.

In another Antara rebuffs his wife, who has chastised him for feeding camel milk to his horse.

“Don’t mention my colt or what I fed it lest I chase you away like a scabby camel,” he says. “The evening milk is his. You lose out, so go moan and scream all you want. Enjoy your dates and cold water from the skin, but if you’re here for the milk, go on your way.

“Remember – other men might capture you. If they do, make sure to line your eyes and dye your hair. You’ll be carried off on one of their camels but that’s when I will saddle The Ostrich.”

Prof Montgomery explains the message of the poem: “Don’t give me a hard time for using the camel’s milk for the horse, because he needs it more than we do, and he allows us to take our place in society, in this unit, to be safe and secure from the agents of destiny.”

Another poem reflects the legacy of Antara’s famed love for his cousin Ablah: “My words are pearls, Ablah, and you the iridescence of its necklace. Noble princess, I race to you on a purebred Mahri [camel] through hills where the rivulets glisten green and myrtle, saxaul, jujube, lote and rose all burst into bloom.”

Antara was considered unworthy of Ablah’s betrothal, and her father requested a dowry of 1,000 Iraqi camels.

“This sets him off on a labours of Hercules kind of expedition, where he has to go and try to win these camels,” Prof Montgomery says. “The first thing he has to do is acquire a horse and a sword, and both the horse and the sword are black, just as he is.”

His sword was said to have been made of material from a meteor.

"Antar and Ablah is one of the great love stories – it's sort of the Romeo and Juliet of the Arabian epic."

Some of the poems addressed to Ablah are tender, but “because it’s not a happy love story, they are a little aggressive and belligerent”.

Antara’s poetry was not written down until the start of the 800s, by Arabic-language scholar Al Asma, who collected oral traditions from tribes passing through the deserts of Basra and Baghdad.

And the 200 years of oral tradition probably led to inaccuracy seeping in, Prof Montgomery says, because the “legend was already in the making”.

“He was the most ferocious warrior in pre-Islamic Arabia. He was black, he was born to an Arab father and a slave mother, and he had to fight for his freedom.

“So he very quickly became an epic hero, someone that lots of generations of Arabs could identify with.”

Very soon he was immortalised almost in the same manner as Hercules. “Hundreds of poems were composed and put in the voice of this warrior-hero.”

In the Romance of Antar epic he travels all the way to Constantinople, fathering children by a Frankish princess and dying by a poisoned arrow.

One of the earlier biographies speculates that “he’s such a ferocious and fantastic warrior that no human can defeat him in battle, so he dies in a sandstorm in the desert. It takes nature and the elements to actually conquer his ferocity of spirit, and not another human being”.

The 5,000-page epic was first printed in Egypt at the end of the 19th century. It was read out in Damascus and Cairo coffee shops, Prof Montgomery says, by full-time reciters.

Using 9th-century Baghdad scholars as a reference point, the library has compiled 26 poems it believes were genuinely written by Antara, although it has also included some from the later epic tradition – “just to give a flavour of it”.

The book will contain about 30 poems ranging from six to 80 lines.

“The most famous poem that he wrote, that’s about 80 lines long, and the legend is that it was so highly thought of that it was written on silk in letters of gold, and was one of the poems that was hung up on the walls of the Kaaba before Islam.”

Antara’s authentic poems indicate he dwelled in the Hijaz and Najd deserts, in modern-day Saudi Arabia.

They are also, Prof Montgomery says, really good.

“Whether you’re reading it in Arabic or, I hope, in our English versions, at the end of it all the poetry is of a surprisingly high quality.”

Antara and a few other pre-Islamic poets are the earliest surviving examples in Arabic of the phenomenon of the desert-warrior poet.

“In the desert poetical tradition, as it’s still sometimes practised in the form of Nabati poetry, some of the same spirit still manages to breathe.”

That Antara’s pre-Islamic poetry was able to successfully propel itself through the advent of Islam, and continue to remain relevant and revered, is a testament to its timeless exploration of the indomitable spirit of the desert warrior.

“In the end, nothing much has changed – you’ve got time and fate, you’ve got man and his community, and you’ve got the desert,” Prof Montgomery says.

“However you respond to those things, there’s only a limited range of responses that human beings would have to that situation.”

For Antara, the only way of dealing with the uncertainty of fate was to show unwavering bravery and confidence in man’s ability to live the true life, Prof Montgomery says.

“This tradition of warrior poetry – of a strong sense of identity and the poet as a hero, of the poet’s voice in this amazing Arabic, expressing this ultimate defiance, bravery and fortitude – in the intervening 15 centuries, not much has changed there.”

While it is very difficult to translate, Antara’s strength of voice, imagination and clarity of imagery are all too clear, Prof Montgomery says.

“We think it deserves to take its place on the world stage. It’s fabulous stuff. It’s great poetry, it’s fun to read and that’s really the message that we want to communicate.

“Every society in every age needs figures who are bigger than life – people with any superpowers or who are able to achieve the maximum that a human being can achieve. In terms of warfare and bravery, that’s what Antara achieves.”

halbustani@thenational.ae