DUBAI // Muslim countries must send more police and army trainers to rebuild Afghanistan because the threat of terrorism poses a bigger risk to the region's stability than to the West's, Nato's top diplomat to the war-torn country said in an interview with The National.

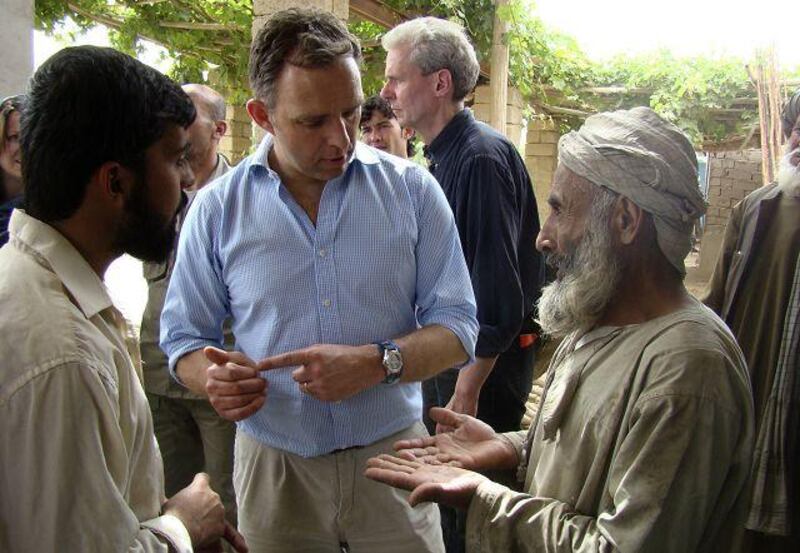

Afghanistan desperately needs to secure its borders and police its cities to protect against insurgent networks and prevent terrorism from spreading across the region, said Mark Sedwill, the Nato senior civilian representative who represents the political leadership of the 28-member alliance. "What we'd like to see is the Muslim world really engaging in Afghanistan both on the development side and military side," he said, though he stressed that he was not asking for Muslim nations to send soldiers to fight.

He said the UAE has offered to support and pay for training, and Jordan has army paramedics in Helmand and Kandahar provinces, where fighting is fiercest, but more could be done by other Muslim-majority nations. "The more it is seen as an international effort and not a western effort the better, because among the Afghan people it creates a greater sense of legitimacy," he said. Mr Sedwill spoke on the eve of what is being called the biggest military offensive since the war began in 2001 as Nato and Afghan forces attempt to seize Kandahar from the Taliban.

Tens of thousands of soldiers are gearing up to descend on the city and surrounding areas as fighters allied to the Taliban flood in for the fight. In an interview in Dubai just before he returned to Kabul, Mr Sedwill warned that Nato forces would be in Afghanistan "for a decade or more" as Nato gradually withdraws from a fighting role next year to supporting the Afghan army. He said the Islamic world has more at stake in Afghanistan than western countries do. "The threat to stability is much greater across the Muslim world than it is in the West. We have attacks like 9/11, we have attacks along the lines of London in 2005 and Madrid, but those are unlikely to destabilise our societies.

"There are vulnerable countries Yemen, Somalia and others which, if this movement of violent extremism with a notionally religious veneer to it gets traction, it is this region that it threatens." "We wouldn't expect Muslim countries to want to put their troops into the front-line operational roles, for obvious reasons, and everyone understands that," said the British-born diplomat. "But the more they can do to build up Afghan capability, military and civil, the better. And there are very high-capability armies across the Muslim world."

He added that Afghanistan was not short of development money. "It's not a question of coming around the Gulf and asking for more money." Mr Sedwill played down the military aspect of the Kandahar campaign and described it as a series of focused operations by Nato soldiers and Afghan law-enforcement officials to root out the Taliban from their hideouts. "This is not a major climactic operation. What we'll see is a series of individual operations. Essentially what we are trying to produce is a rising tide of security so people perceive security is improving. So there will be security operations, but they will be quite targeted in particular areas where the insurgents are dug in."

The fighting will probably last the summer but by the end of the year Nato expects to hand over responsibility for security to Afghans. Kandahar city will have several rings of security checkpoints manned by Afghan police and soldiers to keep militants out. The city is at the heart of the Taliban insurgency and it is hoped the summer offensive will put them permanently on the back foot. "Kandahar is the prize," Mr Sedwill said. "They might carry on as a terrorist movement but they can't really hope to overrun the country again."

This is Nato's second major operation this year, coming on the heels of Operation Moshtarak in rural Marjah in Helmand province, next to Kandahar. The offensive was criticised for not having enough competent Afghans to govern the area after the insurgents left. Mr Sedwill said the lesson from Marjah was to get support from the right tribal elders through shuras, or meetings. "In Marjah what we found was people we were doing [shuras] with weren't fully representative. The local people couldn't get access to the area because the area was in the hands of the Taliban."

For the Kandahar offensive the province's governor, Tooryalai Wesa, has been holding shuras all over the province to whip up support ahead of the offensive. "It won't be perfect but we're putting a lot of effort into it," Mr Sedwill said. He was dismissive of perceptions across the Muslim world that western forces were occupiers and the Taliban were holy fighters. "The notion that there is religious justification for what they are doing when they shoot the deputy mayor of Kandahar whilst he is in the mosque is an extraordinary thing," he said, referring to an assassination on April 20. "The insurgency claim to be fighting us, foreign forces, but actually most of their targeting is against their own people." @Email:hghafour@thenational.ae