TRIPOLI // The head of the Muslim Brotherhood's political affiliate in Libya has a firm handshake, a trim beard and the easy smile of a man for whom things are going well. He talks confidently of tactics, politics and theology.

Mohammed Sawan appears a far more assured man than the one who, four months ago, seemed angry and faltering as he tried to explain why his party came in a distant second in July's national election.

In an interview at his party headquarters in Tripoli, Mr Sawan cheerfully discussed why the liberal-leading coalition that prevailed in those elections - the National Forces Alliance - is failing to live up to its political promise and fragmenting, and why his vanquished Justice and Construction Party is rebounding.

In the fraught political landscape of Libya, a country almost entirely new to democracy and ideology, an elected government has struggled to make decisions, and ministries, as yet unreformed, have floundered to implement them.

Amid a growing unease about the future of the country, Mr Sawan said that his party's star was rising.

His party, many of whose members are also part of the Muslim Brotherhood - although there is no official link between the two groups - is growing in strength because it is "mentally organised and connected" around a clear idea of moderate Islam, he said.

Whether the party succeeds in overhauling its message and agenda, and recovers from its resounding defeat at the polls, it is being watched closely across the region. Its poor showing in July interrupted what until then had been a wave of dramatic electoral successes for Islamist parties in two other North African countries - Egypt and Tunisia.

For Justice and Construction, it is not only a question of whether, like other Islamist parties, it can adapt in an era of fast-paced change following the toppling of a dictator. It must also overcome public suspicion of Islamists in Libya and fears of the Brotherhood, even among the country's overwhelmingly conservative Sunni population.

Members of Libya's new legislature, analysts and diplomats say the party is making progress. It is asserting itself in national politics, while in the provinces, party members are assuming prominent posts on local councils and using youth campaigns, women and political salons to spread their political message.

Force of organisation, political experience and patience may yet enable the group to build substantial support in one of the few Arab countries where their presence had historically been minimal. In the General National Congress, observers have noted that independent members are drawn to vote with Justice and Construction, as are other conservative parties.

The party has regular caucus meetings and, while not totally unified, tends to vote as a body on important issues, such as the nomination of a prime minister. Its manoeuvring was seen to be a key factor in the September election of Mustafa Abushagur as prime minister. Mr Abushagur defeated Mahmoud Jibril, leader of the alliance that won the election, although he was unable to form a government the Congress would support.

Mr Sawan says that the party now has 10,000 members among Libya's population of 5.6 million people, and it identifies with countries such as Tunisia, Egypt and Turkey, where Brotherhood-linked parties dominate, as models. He said his party had been working on its investment portfolio and media relations strategy. People from outside the country, including some from Islamist groups, provided political training and workshops, he said.

If Mr Sawan's plans go ahead, the party could undergo a rapid transformation since it was established officially in March after decades of clandestine and mostly exiled political activity. Outlawed along with all other political movements under Muammar Qaddafi, many members of the Brotherhood spent years in prison.

"The culture of politics in Libya is very, very, very weak," said Salim Betmal, a party member and head of Misurata's local council. He said Qaddafi encouraged Libyans to think along tribal lines and fostered fear of other organised political groups.

Mr Betmal is a brisk man who read and signed letters brought to him by assistants during a long interview in a hotel that was once the technology college where he taught. He was never a Brotherhood member but chose to join the party because he felt it was his best chance to make a political impact.

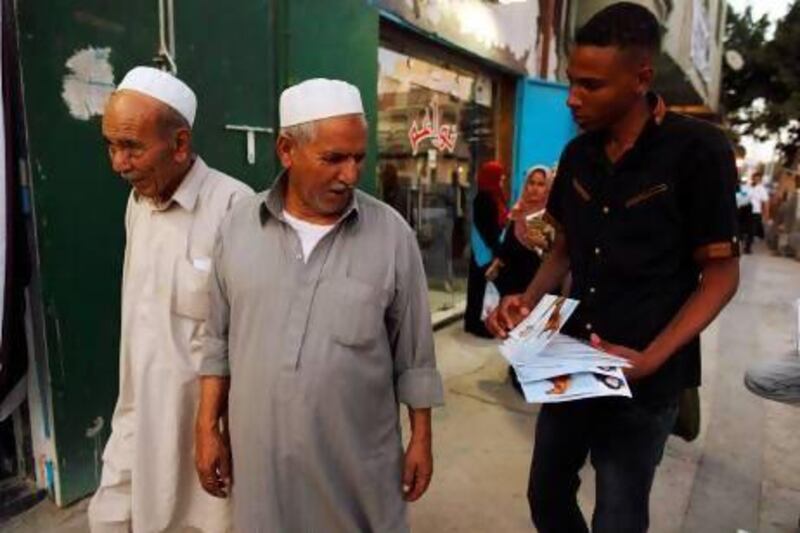

In Misurata, he said, the party has been reaching out. It has about 650 members and its youngest members distribute party leaflets. It hosts a weekly political discussion, a kind of political salon, which is open to everyone.

The party's strengths are its structure and organisation, he said, which he attributed to its Brotherhood roots. He said most Brotherhood members were politically trained and had offices across the country, which gives its sister political party a ready-made base.

In Benghazi, the party has 1,500 members, a seven-storey office with views of the sea and separate office floors for women and youth programmes. But Ramadan Al Darsi, a Congress member and deputy head of the city's branch, said that many challenges still lay in combating an instinctive mistrust of Islamists.

"The worry about the Islamists in general is justified, because Islamists are different from each other. They are not all the same colour," he said.

In Benghazi, after the death of four Americans in the September 11 attack on the US consulate, hundreds of people rallied against Islamist militias who were suspected of involvement.

Islamist politicians have been subjected to some of the same suspicions, he said, but the party is working on convincing people that it "respects freedom and democracy ... and we don't have something scary we are going to force the people to do".

Last month, the Congress began discussing nominations for a 60-member body that will be responsible for writing a constitution. The mechanisms of electing the body were still unclear, but it seemed likely that the divisions between Islamist and secular ideologies would emerge as the document was debated. In Tunisia, similar constitutional discussions involving women and blasphemy have been met with protests.

Analysts say that Justice and Construction's leaders are eminently patient, aware that it will take some time to gain popular support and there will be challenges.

The National Forces Alliance, the electoral winner, is working on being more unified, with weekly meetings, said Amina Meghrerbi, a member from the alliance.

But during a four-month power vacuum after elections, the country's security has slipped noticeably and some say that any party with the power to lead the country would be welcomed.

On Benghazi's seafront recently, teachers Amal Al Abendera and Amal Al Jeffala were out one evening with their children.

Both had voted for Mr Jibril's liberal alliance, but did not understand how he had failed to become prime minister. Mr Jibril was good, Ms Jeffala said, but, "the Justice and Construction party is OK. We need someone to help the country - with actions, not speeches".