MANILA // Esmael Enog heard gunfire and saw men with with high-powered rifles carry out one of the most heinous crimes in Philippine history: the massacre of 57 people, including 31 journalists, on a November morning three years ago.

But nine months after testifying in court last July and pointing a finger at a politically powerful family, Enog vanished. His body was found in a sack near marshland last month, chain-sawed into pieces, according to his lawyer.

Two other witnesses have been murdered, casting doubt over whether anyone will be brought to justice for the nation's bloodiest election-related violence and the deadliest single attack on the press ever documented.

The difficulty of securing witnesses - and keeping them alive - is as a formidable test for the two-year-old government of Benigno Aquino, the president, who has nurtured a graft-fighting image and vowed swift resolution of the case.

Whether he can do that depends, in part, on how deeply he can reform a judicial system plagued for decades by corruption.

The Heritage Foundation, the think tank based in Washington, rates the country's judiciary as inefficient and says it remains susceptible to political interference.

"Despite some progress, the government's anti-corruption efforts have been too inconsistent to eradicate bribery and graft effectively."

Corruption and lax rule of law remain among the biggest turn-offs to foreign investors, who favour the nearby emerging markets of Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia.

The 2009 massacre in the southern province of Maguindanao was horrific even by the standards of the Philippines, whose restive south is riven by political and insurgent violence.

Then, a convoy of vehicles en route to register Esmael Mangudadatu, an opposition candidate for provincial governor, was ambushed by about 100 gunmen on a lonely stretch of motorway. The victims were driven to the top of a hill, separated into groups of men and women and then shot with high-powered firearms at close range.

Several women were allegedly raped before they were killed. Some were buried alive in mass graves.

Prosecutors identified a total of 103 witnesses but rights groups say many have been harassed even while under a state witness protection programme. One of the witnesses who was killed, Suwaib Upham, was gunned down after failing to receive the government protection he requested.

"We know of several cases of witnesses or their families who have been killed, threatened or harassed," said Elaine Pearson, the deputy director of Human Rights Watch in Asia. "If the government can't get it together for this case, then what hope is there for all the other cases of human rights violations?"

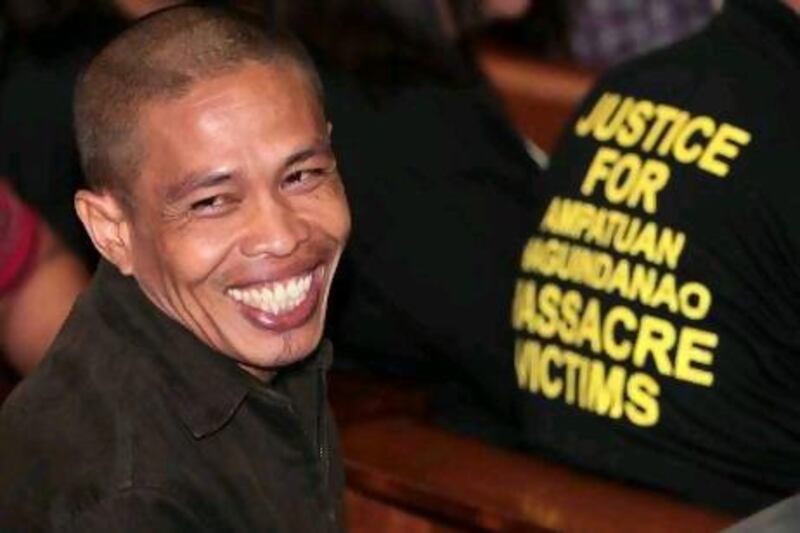

The main defendants are the politically powerful Ampatuan family. Excavating equipment belonging to the local government, run by the family, was found at the site where it was used to dig graves so big two vehicles were buried with the bodies. Members of the family's private militia have also been charged.

Francisco Baraan, an undersecretary at the Department of Justice, said bringing to justice nearly 200 people accused in the murders will be difficult. "Even if we want to resolve this case at the soonest possible time, the sheer number of accused will make it difficult for us to speed up the process," he said.

The Ampatuan family has dominated politics in Maguindanao for nearly a decade and enjoyed close ties to former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, now in detention while on trial on electoral fraud and corruption charges.

One witness, Lakmudin Saliao, testified in September 2010 that the massacre was planned over a family gathering during which the patriarch, Andal Ampatuan Sr, asked how they could prevent a challenge by their political rival, Esmael Mangudadatu. "That's easy. If they come here, just kill them all," his son, Andal Ampatuan Jr, replied according to the testimony by Mr Saliao, who had served at the family dinner that evening.

Andal Ampatuan Sr and his four sons are in jail awaiting trial. Two other Ampatuan clan members, a brother of Andal Sr and a grandson, are also in detention.

Esmael Enog had worked as a driver for the Ampatuans. He testified he brought dozens of gunmen to a checkpoint where the convoy was stopped. He heard the gunfire and identified four members of a local militia linked to the massacre.

He declined state protection, partly to be with his family. Instead, he tried to hide in a farming village in Maguindanao, fearing about 100 loyal Ampatuan militia members still at large, said his lawyer, Nena Santos. He went missing in April.

Local police, however, have denied finding Enog's body and a search for him, dead or alive, continues.

At the current pace, it could take decades for a final judgment, said opposition senator Joker Arroyo.

The court is now hearing arguments on the Ampatuans' bail petition and has not begun examining the merits of all 57 counts of murder against them. Ninety-six of 196 people accused in the massacre have been arrested, including seven members of the Ampatuan clan, but only 64 have been arraigned.

The patriarch, Andal, faces separate poll fraud charges along with Ms Arroyo, the former president, and the former head of the election commission. Under Ms Arroyo, the Ampatuans tightened their political grip over Maguindanao, delivering votes for Ms Arroyo and her party in exchange for financial and political support.

Mr Aquino sees this as a litmus test of the justice system. But press advocates are impatient and want him to put more resources into it. They highlight another disturbing trend: journalists who report on provincial corruption continue to be assassinated.

Since Mr Aquino came to office in July 2010, 17 journalists have been killed, although press freedom groups say only eight deaths were work-related. During Ms Arroyo's nine-year rule, 107 journalists were killed, 79 deemed work related.

Most cases remain unresolved.

"We need to see a strong resolve against impunity in the Philippines on the part of the president," says Romel Bagares, a private lawyer helping prosecute the Ampatuans. "From the very beginning he should have made the massacre trial the showcase of his administration's human rights policy."