Microplastics in tap and bottled water do not appear to pose a health risk to humans, the World Health Organisation has found.

In its first report on the issue, the United Nations health body said larger particles, and most smaller ones, pass through the body without being absorbed.

However, the findings came with a big caveat. Experts warned that current evidence was fairly limited and much more investigation was needed to determine health threats to humans.

“Just because we’re ingesting them [microplastics] doesn’t mean we have a risk to human health,” said Bruce Gordon, WHO’s coordinator of water, sanitation and hygiene.

“The main conclusion is, if you are a consumer drinking bottled water or tap water, you shouldn’t necessarily be concerned.”

Caution was also urged over the results as tests were not standardised with different researchers using different filters.

"To say one source of water has 1,000 microparticles a litre and another has only one, could simply be dependent on the filter size used,” said Dr Gordon.

And the WHO called for further research to assess the potential risks as studies into plastic contamination are in their infancy. "We urgently need to know more," the WHO said.

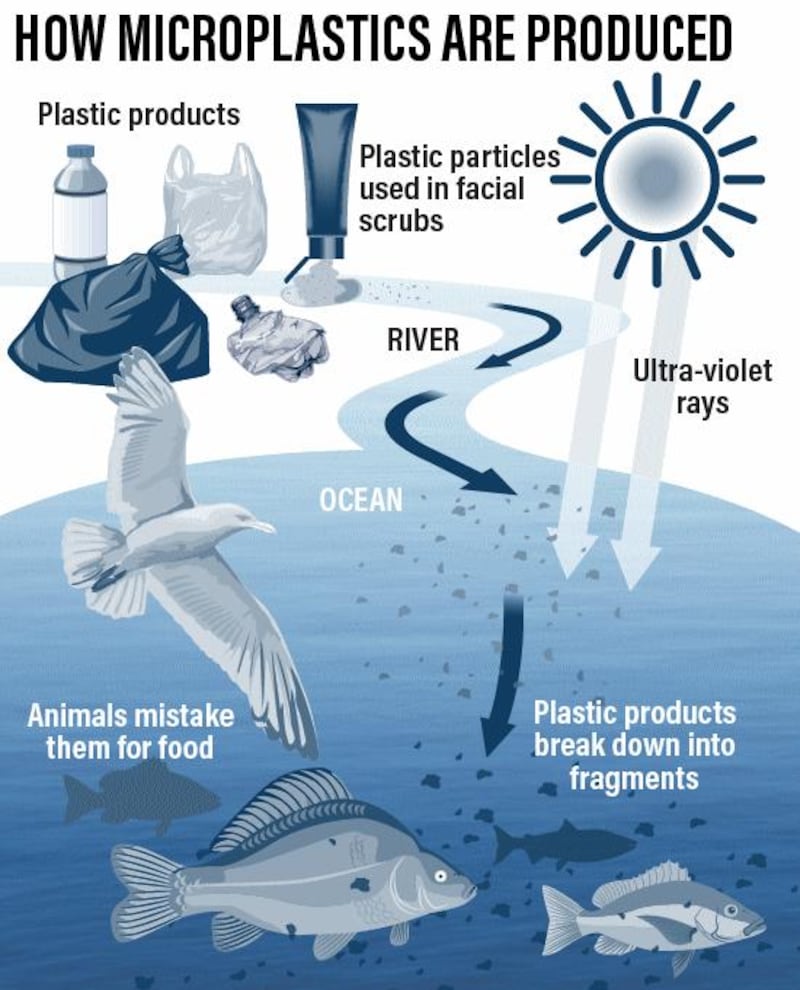

Microplastics are defined as less than 5mm in length, and have been found in lakes, rivers and drinking water supplies. Most find their way there as a result of treatment and distribution systems, the study found. Dr Gordon said much work should be directed towards ensuring the availability of clean drinking water for all as bacteria found in some water supplies can cause typhoid and cholera. "Two billion people drink water that is faecally contaminated. That causes one million deaths a year and must be the focus.”

The WHO said proper waste water treatment to remove dangerous bacteria should also remove more than 90 per cent of microplastics.

Plastic production has surged in recent years, with current usage set to double again by 2025.

Miniscule elements of polymers have been found in bottled water, thought to have been deposited by screw-on plastic caps.

The UN report’s co-author, Jennifer de France, said further research should also examine the presence of microplastics in the air and our food supplies.

"We need to know the number of particles that have been detected, the size of these particles, the shapes, as well as the chemical composition,” she said.

Microplastics have been found in snow, with airborne particles finding their way to alpine environments.

Research previously warned chemicals used in most plastic bottles could damage sperm quality.

Studies showed phthalates, also found in solvents and personal care products, can lower sperm count and alter their shape.

Scientists examined the impact of plastics on fertility of 108 young Chinese men, with results published in the international journal "science of the total environment" in 2016.

Results revealed significant concentrations of phthalates in urine samples of men aged 18 to 22, with nearly half recording values exceeding a safe threshold.

“This scientific research and development is vital,” said Dr Pankaj Shrivastav, medical director at the Conceive Fertility clinic in Dubai, about the findings.

“It is imperative that we as medical physicians take this kind of knowledge to the public and make them aware of potential environmental dangers.”