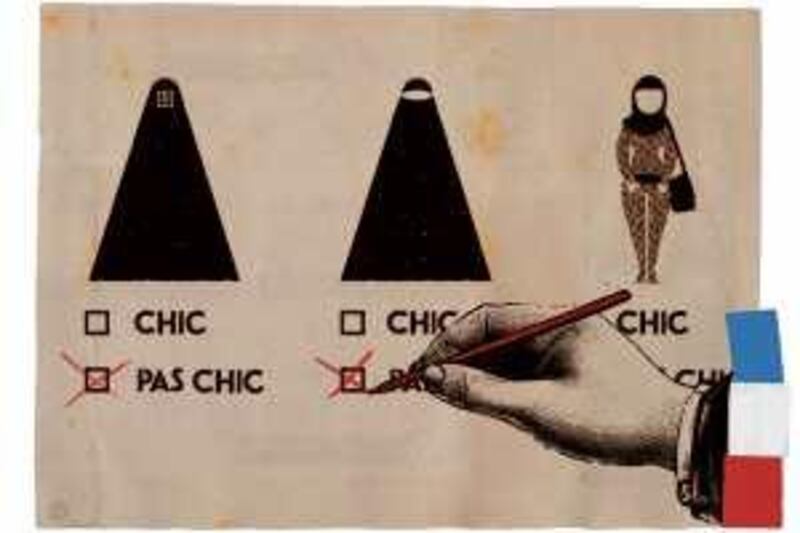

Muslim women locked in a tyrannical stranglehold by Muslim men can rest easy. The French president Nicolas Sarkozy is ready to rescue us. In a breathtaking moment of hubris, Mr Sarkozy said in a speech to France's parliament that there was no place for the burqa in France. "In our country, we cannot accept that women be prisoners behind a screen, cut off from all social life, deprived of all identity," Mr Sarkozy said. "The burqa is not a religious sign, it's a sign of subservience, a sign of debasement - I want to say it solemnly. It will not be welcome on the territory of the French Republic."

For the record, I wear the abaya and niqab in Saudi Arabia. I wear them because it is my choice. Contrary to popular western myth, the abaya is not forced on women in Saudi Arabia, which, as an Islamic country, requires women only to cover the details of their bodies. While I am living abroad I wear a different style and colour hijab that is conducive to the environment I live in. I choose not to wear the common black abaya in Britain for my own personal reasons that are nobody's business but my own. But if I ever decide to put on the abaya and niqab the way I do in Saudi Arabia, that also is my own business.

When I was 16, I went on holiday with my family to Geneva. I left my hijab at home, wore short skirts and didn't cover my hair. I dressed typically western. My brother was furious, but my mother simply told him that if I were forced to wear the hijab I might grow to hate it. She wanted me to make my own choice and grow to love it. It was a turning point for me because I realised that it was my choice. I weighed what could be gained and lost by wearing it. I discovered that it strengthened my self-respect and the respect of others.

I enjoy socialising and working with westerners. I quickly realised that once in the West the key to successfully adapting to their society is really about who I am, how I present myself, and how I interact with my colleagues and new friends. It's not based on what I wear. I have an Arab friend who grew up in a home where the hijab was optional. When she married a Saudi he forced her to wear it. She grew to hate it and at every opportunity away from the home, she took it off.

It is human nature to rebel against something forced upon us. A woman made to wear the burqa is not going to wear one in public if she can get away from it. She will gladly rip it off the moment she is away from her family. So it begs the question why women who go about their business independently of their families are still wearing it. The simple answer is because they want to. The president is echoing what many French politicians have been demanding the past few years. They want to create a commission to examine the possibility of a full-scale burqa ban. The issue is divisive, as some politicians say it will create tensions between France's Muslim population of five million people and non-Muslims.

Mr Sarkozy provides us with yet another example of how western nations define human rights and the oppression of women. It is assumed that if a woman is wearing the burqa, it has been forced on her. Because, really, who in her right mind would wear such a thing? But in Saudi culture the abaya is part of our identity, an identity that most of us happily embrace. Young Saudi girls often emulate their mothers and older sisters by wearing the abaya even before they hit puberty. This differs little from young western girls who wear their mothers' clothing and high heels.

Of course, there are many women who are made to wear the burqa, although that is not much of a problem in Saudi Arabia. In rural areas of Pakistan and in Afghanistan under the Taliban, forcing the burqa on women is not uncommon. These areas are mired in extreme poverty. Education, especially for girls, is minimal. Often the parents have no education. Compelling women to wear the burqa is only a symptom of larger abuse issues in the family. If a woman is forced to wear the burqa she is also likely to be a victim of sexual, physical and emotional abuse.

While this affects a minority of Muslim women, they nonetheless need to be protected. But a complete ban is counterproductive. France is willing to consider the easy route by simply banning the burqa altogether rather than bother itself with considering what Muslim women want. A potential solution, since we are talking about women being made to do something against their will, is to treat it as domestic violence. By incorporating language into existing domestic violence laws, wearing of the burqa under duress can be addressed. This allows less government intrusion, strengthens laws to minimise oppression and still allows women a choice of how they want to present themselves in public.

Mr Sarkozy is generalising about Muslim women with blanket statements that the burqa is oppressive. That is not based on reality and penalises Muslim women who chose to wear it. Using existing investigative techniques by social workers and law enforcement to identify abused women at schools, the workplace, public housing or when applying for public assistance is a far more practical solution. There seems to be the misperception that wearing the burqa excludes women from participating in French society. Somehow the burqa prevents women from asking the clerk at the grocery store what's on sale, having parent-teacher conferences at their children's school, or running for municipal office.

What the French government is demanding is that Muslim women become active members of society under the government's rules. Rules that apparently don't apply to Hasidic Jews or Catholic school girls forced to wear pleated skirts and knee-high socks. These forms of cultural and religious dress are acceptable by western standards, yet Muslims are excluded from the club. By imposing a dress code the government sets the parameters of social etiquette. In effect, by mandating a dress code the French government excludes many Muslim women from society. Muslim women who believe it is their right to wear the burqa simply will not leave their homes. They will not engage the grocer and their children's teacher. They will not run for public office. The oppression will not come from their culture or religion, but from the French Republic.

What is lost in the hubbub of public debate over this cockamamie burqa ban proposal is that we allow our civil liberties slowly to erode. In 2004, the hijab, along with other religious symbols, was banned in France's public institutions. Today the French take another step by considering banning yet another piece of clothing. Will the French next see the Islamic requirement of praying five times a day as a sign of oppression and implement a ban? Will it decide that Hasidic Jewish women's scarves and conservative dress required by Jewish law is oppressive? Where do they draw the line between oppression and freedom?

The Muslim community has always viewed France as friendly and tolerant. Now France's Muslims find themselves more marginalised than ever as the West continues to determine what is best for them. France should know better. There are many French citizens alive today who remember when one segment of French society was once ostracised, had its religious and cultural symbols stolen or destroyed, denied the right to worship or wear clothing that identified their religion and ultimately put to death.

It seems that France is on the path to revisiting that part of its history. Sabria Jawhar is the former bureau chief for the English-language newspaper Saudi Gazette in Jeddah. She also writes for The Huffington Post. She is a PhD student at the University of Newcastle in Britain