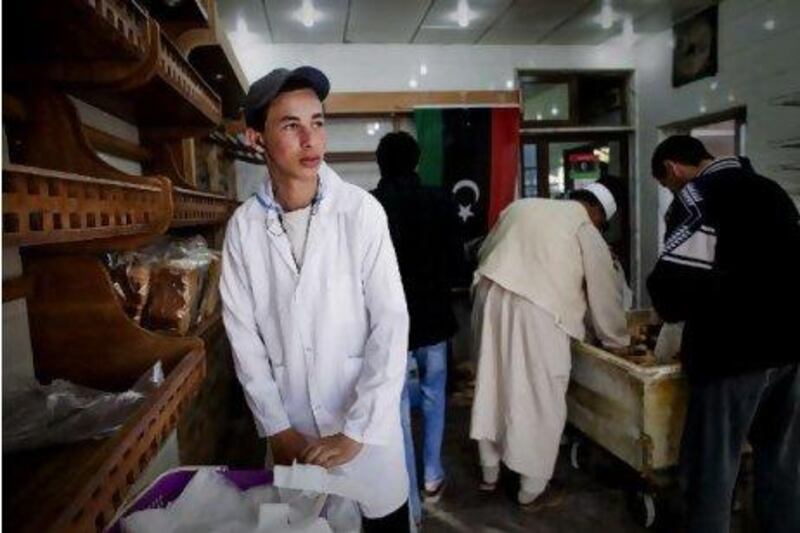

BENGHAZI, LIBYA // In a bakery in Hay al Salam, a working class Benghazi neighbourhood, young men shovelled loaves of bread into an oven.

Most were volunteers who had come to work at Bargo bakery after the start of the revolution, replacing foreign workers who fled the country at the beginning of the uprising.

"I came here on my own because Libyans need my work," said Mokhtar Lebeidi, a 19-year-old volunteer from the neighbourhood. On Friday, wearing white overalls and a baseball cap, he baked while listening to music with earphones. Mr Lebeidi said that, like most of his fellow volunteers, he did not know how to make bread before coming here.

The newly formed Benghazi local council has rallied young volunteers like Mr Lebeidi to fill the void left by fleeing foreign workers. Before the revolution, Libya's economy was heavily dependent on foreign labour from Egypt, Asia, Sudan, Chad and other places.

Almost half a million people fled the country over the past two months, the UN refugee agency reported last week. All but 100,000 were foreigners.

Last week, Abdallah Shamia, a rebel official on the economic and financial crisis team of the Benghazi-based interim government, said the rebel leadership wants to shift the local economy away from dependence on foreign aid.

"We have to plan our need and secure our goods independently," Mr Shamia said from his office overlooking the Mediterranean.

This is why, he said, the new local and national authorities are encouraging volunteers to work in the bakeries and in the fields, helping to harvest produce.

Ahmad Badi is the man in charge of gathering young men willing to help the revolutionary cause by providing such labour. He is the head of the National Association for Volunteer Work which has provided humanitarian help and organised the work of volunteers in Benghazi in the past weeks.

"Our people need bread and vegetables. It is difficult to bring them from the outside," he said.

Until now, Mr Badi gathered 70 young men to work in the local bakeries. They started training at the end of last week.

"Before the revolution, the majority of the bakers working here were Egyptians," said Faraj Bargo, the 38-year-old owner of the bakery in Hay al Salam. Mr Bargo owns two other shops. One of them has closed because of the lack of staff.

Production has decreased by 50 per cent and Mr Bargo is now relying on the work of volunteers, hoping that the authorities will send other young men to help meet his staffing needs. Before the uprising, his shops were baking 12 different kinds of bread. Now, his ovens come out with just one type of loaf.

"This is what people need now," he said.

Foreign workers were not just bakers in Libya. Fruits and vegetables sold in the streets of Benghazi come now from Egypt, though farms in eastern Libya are still able to produce. With the flight of all the foreign workers, there has been nobody to pick the ripened crops, vendors at the local market said. Mr Badi has already started looking for volunteers to work in the fields, in co-ordination with the local farmers' union.

Last month, his association found a solution to provide labour for another unpopular job in the city: collecting the rubbish, a task once performed by migrants from Africa. Public workers from a government construction company - who were sitting at home because of the violence - were asked to clean the city instead.

For days, Libyan Boy Scouts had been sweeping the streets of Benghazi. They were the first organised association to take over for the foreign workers.

Last week, Mohammed Bughrara, a 22-year-old Boy Scout leader, said his colleagues in Benghazi and in Darna had even dug graves in the local cemeteries, a work once done mostly by immigrants from Chad.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae