Cambodia's Cham Muslims lived in obscurity for centuries and were nearly wiped out by the Khmer Rouge. Now Gulf states, US officials and militant Islamists are all taking an interest, Brian Calvert reports.

"Villagers of Koh Phal," the Khmer Rouge soldiers broadcast from their riverboat, "throw down your weapons and come to live together with the Revolutionary Organisation." It was a night during Ramadan in 1975, and the villagers were Cambodian Muslims, or Chams, the sole inhabitants of a fertile island in the Mekong river. For two years, the Khmer Rouge had been arresting the village's leaders, ordering its women to cut their hair and forbidding the practice of Islam. Now the men of the village had had enough. They dug up caches of swords, sharpened their hatchets and shaved their heads, the better to differentiate themselves from the enemy, whose broadcast through the darkness went unanswered.

The next day the Khmer Rouge unleashed dozens of soldiers, whose firearms easily outmatched the villagers' crude weapons. For two days, the soldiers ravaged the island, shooting men, women and children. Boats strafed the banks and artillery hammered the interior, destroying the island's mosque, homes and schools. By the time the ill-fated uprising was put down, most of the 1,800 villagers had been killed or captured, a lucky few floating down the river in escape. And with that, the Island of Harvest, its name until then, became the Island of Ashes, its name today.

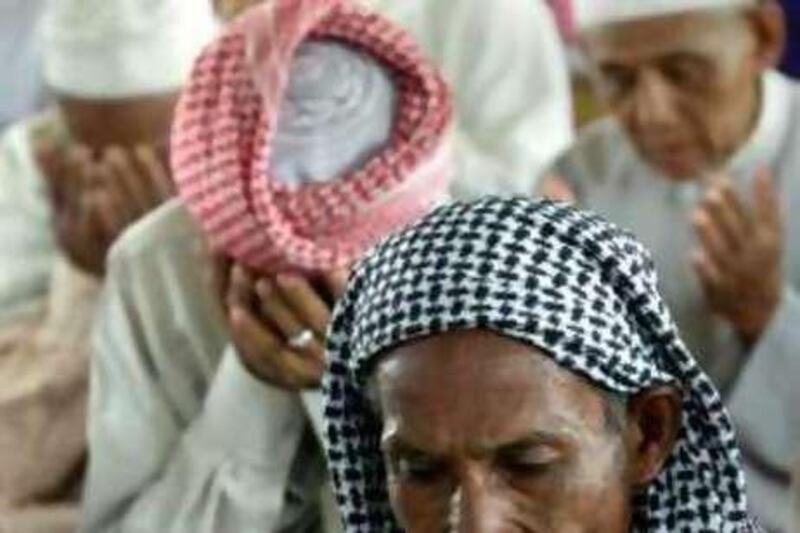

Sitting on the steps of the International Dubai Mosque in Phnom Penh one recent morning, Chi Hassan, a 69-year-old Cham farmer, recalled the uprising and other depredations suffered by the Chams under the Khmer Rouge. The regime's lethal communist experiment - which abolished schools, money and religion, severed family ties and marched the entire populace into vast agrarian collectives - led to the deaths of nearly two million Cambodians, a little less than 25 per cent of the population. But the Chams suffered disproportionately. Numbers vary, but scholars estimate that between 40 and 70 per cent of them died under the Khmer Rouge. By the time the regime fell in 1979, fewer than 200,000 Chams remained; most of their 130 mosques had been destroyed, and only 20 of their clergy were still alive.

"While we were in the cooperatives, we lost all religion," Chi said, his face shaded from the morning sun by a light turban, his hands thick from years of fieldwork. "No Cham religion, nor Khmer religion. We only had revolutionary religion." Before their near-eradication under the Khmer Rouge, the Chams were an obscure, nationless and relatively isolated branch of the Muslim ummah. Violently driven out of central Vietnam in 1471, they have long practised a folk version of Islam that retains an underlying indigenous belief in animism and magic. In the squalid, unstable years since the fall of the Khmer Rouge, the Chams have continued to struggle: even by Cambodian standards, their literacy rates are low, their maternal mortality rates high and their villages poor. But that could all be about to change - because suddenly, a host of people have taken a strategic interest in the Chams.

In recent years, the Chams have become the beneficiaries of attention from wealthy Gulf states, fundamentalist Muslim groups, the US State Department and - perhaps most remarkably - their own government. With all that attention, things are looking up for Cambodia's Muslims. Chi had come to the International Dubai Mosque, which was built in 1994 with the help of a wealthy donor from the Emirates, to see his wife off for the Haj. The old man sat among a group of other Chams waiting for a van to take them to the airport, part of an increasing number able to make the pilgrimage, an impossibility until recently. Two thin date palms poked over a dusty drive, and most of the grounds were taken up by a giant mud puddle strewn with trash. Near the front gate, a two-umbrella drink stand sold refreshments to travellers and roosters crowed from the slums beyond the barbed-wired topped walls.

The rundown mosque has become the focal point of the new-found interest Gulf states have shown in Cambodia. Earlier this year, high-level delegations from both Kuwait and Qatar visited Cambodia, eyeing the country's agricultural land as part of their search for food reserves. The Qatar delegation, led by prime minister Sheikh Hamad bin Jassem bin Jabor Al Thani, offered more than $200 million (Dh735m) in loans for irrigation projects, an air link and a proposal to import Cambodian labour to the Gulf. The Kuwaitis, on a regional tour with prime minister Sheikh Nasser al Mohammad al Sabah, promised $406m (Dh1,491m) in soft loans for irrigation and road development. But rice wasn't all the Kuwaitis were interested in cultivating. Tied to their aid package was a $5m (Dh18.4m) grant to refurbish the International Dubai Mosque and build an Islamic centre inside its walls, replacing the compound's sprawling mud puddle.

Other Muslim aid organisations from the Middle East have preceded Kuwait and Qatar's ventures - often with the effect of importing new religious norms to Cambodia. A Middle Eastern facilitator of Muslim aid to Cambodia told me that as many as 300 Saudi Salafist mosques have gone up in Cambodia in the past decade, accompanying a rise in Cham Arabic speakers from a few hundred to as many as 7,000. This purer Islam is welcomed by some of the younger Chams, who reject the animism that their ancestors mixed with the faith. "A number of Cham students pursue their Islamic teaching abroad in the hope of strengthening and improving Islam in their communities," said Farina So, a 28-year-old who leads a Cham oral history project for the Documentation Center of Cambodia, an outfit that catalogues Khmer Rouge atrocities. According to So, the older Cham generations were "influenced by Hinduism, Buddhism, superstition, tradition," while younger Chams are more interested in obtaining "pure Islamic teachings from Arabic countries."

What concerns many Muslims, Cambodian leaders and Americans, however, is that the Chams' historic poverty and frustration have also made them susceptible to aid and influence from the most radical Islamic groups. In 2003, Cambodian officials discovered that an Islamic school an hour outside the capital was channelling money for al Qa'eda through something called the Om al Qura Foundation. Four suspected terrorists, including one Cham, were arrested, and 28 foreign teachers were ejected from the country. The four connected to Om al Qura, caught on a tip from US intelligence, had received $50,000 (Dh183,650) from al Qa'eda to "launch an attack in the region," according to South-East Asian terrorism expert Zachary Abuza. (The school has reopened as the Cambodian Islamic Center, overseen directly by Cambodia's mufti and forswearing extremism. Although I was met with suspicion by staff there, I was greeted warmly by a clutch of Cham teenagers at its adjacent girls' school, the Alrahmani Mosque, who gushed over the recent removal of a ban on headscarves in Cambodia.)

Later on in 2003, the operations chief for the Indonesian militant group Jemaah Islamiyah, Riduan Isamuddin, aka Hambali, was arrested in Thailand, following a sojourn in Cambodia, where he had lived in a backpacker ghetto abutting the International Dubai Mosque. These two incidents have made the US government especially watchful of the Chams, although the Americans have proceeded with a surprisingly light touch in their dealings with the group. While aid money flows in from Middle Eastern organisations, the United States is offering up its own soft power initiatives, the US charges d'affaires Piper Campbell told me. The US pays for programming on Voice of Cham radio through a small-grants programme, offers language training scholarships in villages and has reached out in recent years to Cambodia's Muslim leadership. Several million dollars from the roughly $58m (Dh213m) the US puts into Cambodia each year benefits Chams in some way, she said.

For the past three years, the US has held an Iftar event at its fortress-like embassy in Phnom Penh. This year, addressing the gathered Muslim dignitaries, including the country's mufti, who offered the sunset Maghreb prayer, Campbell warned of the difficulties religious groups face from "outside influence, which can often be carried through financial or material aid." "This is a particularly difficult issue in Cambodia, as some of the smaller communities are extremely poor and desire any assistance they can get in order to develop," she told the Cham leaders. "You have the obligation to ensure that the expectations that the donors have are realistic, and also to ensure that meeting those expectations will help, not harm, your constituents."

Yet the Americans may face an uphill battle in getting their message across. Another guest at the Iftar, Zakaryya Adam, a Cham lawmaker with the ruling Cambodian People's Party, told me later: "I would say that before September 11, when Chams saw the westerner come here, they welcomed them warmly. After September 11, Chams hate the westerners, because they have heard that westerners always perceive them with negative perspectives."

Ahmed Yahya is another Cham politician who hates the idea of Chams being tarnished with guilt by association. "If I'm inside the mosque, and I pray with Hambali, I'm involved with terrorism?" he asked. "It's not fair." Perhaps more than anyone else, Yahya stands at the centre of the Chams' recent change of fortune. A politician who has moved in recent years from Cambodia's quixotic opposition parties to the inner sanctum of the Cambodian People's Party, Yahya embodies the Chams' recent rise to relevance in Cambodian politics.

He views aid from Gulf states as a means not only to improve the Chams' livelihoods, but also to insulate them from more radical influences. He says he saw Cambodia's agricultural potential as a way to focus Middle Eastern attention on Cambodia's needs. He encouraged and coached the Prime Minister Hun Sen through many of his overtures to the Middle East. Voice of Cham radio was his brainchild, and he played a lead role in initiating the agricultural outreach to Qatar and Kuwait.

"So much land," he said recently, sitting in an office at the International Dubai Mosque, where, outside the window, two dump trucks and one tiny bulldozer sat idle in the shade of two palm trees. "Cambodia needs help from them to help the farmer develop in his field." Cambodian farmers - who make up 80 per cent of the country's population of 14 million - can typically only grow one crop of rice per year, depending on the monsoon rains, because of the lack of irrigation. With help from Gulf investors, Yahya hopes to add a second harvest and to cultivate Basmati rice - the strain preferred in the Middle East. "We'll export the rice together," he said.

The prospect of economic aid from the Middle East has turned the Chams into an increasingly important group in Cambodian politics. Following the Kuwaiti visit, prime minister Hun Sen announced that he was lifting a ban on headscarves for Cham girls in schools. He also had a prayer room built at Phnom Penh International Airport and financed an hour of airtime a day for Voice of Cham. As early as January, the prime minister is scheduled to make a trip through the Gulf states, and Cambodia has already begun diplomatic operations at a new embassy in Kuwait.

But for all that, the Chams have yet to see much of the aid that has been promised to them. During my visit with him, Yahya took me on a brief tour of the International Dubai Mosque - plainly in dire need of its $5m facelift. The mosque shows green blotches of mold and water marks on its ceiling. The upstairs is in complete disrepair, dusty, with broken fans heaped in a corner, grime everywhere. It is only accessible across a pool of sludge on the south side of the building, via a bridge of broken concrete blocks near the pen of a bleating goat.

And so the Chams at the mosque - and all across Cambodia - wait. They wait for their prime minister to make an appearance in the Middle East, wait for the jobs they might land in the Gulf, wait for rice cultivation plans to be drawn up, deals to be signed. Thirty years after they were nearly destroyed and more than 500 years after they fled their homeland, the Chams wait for their fortunes to turn.

Brian Calvert is a writer based in South East Asia, covering military and security affairs. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Christian Science Monitor, and elsewhere.