In the past year there has been a surge of interest and debate on the topic of Emirati identity and its future. Through conferences, journalism and public and private dialogue, we have debated the perils facing local culture and we have charted strategies to encourage expatriate populations to appreciate and embrace the unique aspects of the Emirates.

The refreshing initiative of students from Zayed University, along with The National, to bring local and expat women into meaningful dialogue as reported in last Saturday's edition, is an example of this dynamic and valuable exercise. Nevertheless I would like to suggest that one aspect of this important debate has been oversimplified. It is widely believed that the influx of expat populations to the UAE is the key cause of the dilution of local culture. My observation is that the erosion of national identity is a sad phenomenon besetting expat as well as local communities. Both are being simultaneously stripped of their national sensibilities in favour of modern lifestyles.

Expatriates make their way to the UAE on the strict basis of professional merit. As they set up shop or take on a new job, they start to embrace values paramount to this society, like excellence and professional achievement. Financial achievement and individual self-sufficiency become driving forces for individuals and families alike, replacing a sense of self-definition through sect, religion or nationality. This is agreeable to most and is welcomed as a refreshing set of meritocratic ideals.

But as months and years go by, social and urban factors compound the supremacy of the workplace over previous values and national affiliation recedes even further among expats. In some case nationalities even become a burden. In the absence of urban venues and public experiences that promote the kind of cross-cultural communication that would quench one's curiosities, people are left only with the workplace to build their cultural impressions of others.

One has to live in Dubai for only a few days to notice how the workforce is racially labelled and how professional stereotypes define ethnic groups. It is not uncommon to assume a Brit in the UAE is a high-ranking executive with a leisurely life, while a Lebanese is an aggressive businessman. Only in this country is "construction worker" interchangeable with "Indian" or "housemaid" with "Filipina". It is vile and reductionist, and most disturbing when on the tongues of schoolchildren.

According to the office paradigm of understanding ethnicities, the local is often reduced by the foreigner to a sponsor or a boss. And let's admit it, regardless what city one lives in, inviting the boss out for a dinner or a game of pool is cumbersome. That is how many opportunities continue to be lost on that level for locals and expats to know each other better. Due to this ensuing circumstance, the local has also been victimised. He has been unfairly cemented in the expat psyche as inaccessible.

Ethnic groups in the UAE are further under-represented because of the scarcity of ethnic associations with cultural mandates. These are the entities that give birth to artistic and social expressions that invoke aspects of a national culture in a foreign country. Readers should think of the variety of Arab-American associations that helped, over the decades, to bring a visible standing to the community in the US. Incidentally, this model brings forth ethnic representatives to advise the national political body on community issues.

Without organised ethnic communities and their leaders in the UAE, dialogue between expats and the local body has been restricted to consular and personal levels only. The UAE can formulate legislation that encourages the creation of such cultural associations, which will give voice to many, and equally aid the locals in reaching out to expats more systemically. Urban planning also continues to inadvertently suppress ethnic groups from coming together in a way which could facilitate displays of heritage.

With the major cities in the UAE rigidly zoned according to industrial, commercial and residential areas, members of any ethnic groups are unlikely to be able to live close to one another or build neighbourhoods that encourage bonding and manifestations of identity. The country may pride itself with an array of ethnic restaurants, but barely any ethnic neighbourhoods exist. Dubai doesn't seem close to having its own Chinatown, Latin Quarter or a Little Cairo. The few old neighbourhoods which have a mixed ethnic feel - Bur Dubai and Satwa, for example - have already been identified for reconstruction into modern luxurious areas, wiping away the bit of colour they gave the city.

No ethnic community in the UAE currently holds its own place in any enduring sense. In Dubai, even the few national clubs don't communicate much with the rest of the city because they are walled off and cordoned on a single road only, Oud Metha. The blame for many of these cultural misunderstandings can be traced to the complacency of the national media, which has done little to create a platform for cross-ethnic introductions.

In four years of making cultural films in this country, I have encountered groups of people from regions such as Myanmar, Malaysia, Kenya and Peru. They are numerous in our cities, but don't occupy an inch of our TV screens, which only furnish imported entertainment and snippets of local life that lack a guiding context. In other cosmopolitan countries, such as Canada and the UK, multiculturalism rises to its true meaning through programmes designed to enhance cultural understanding in all directions. I learnt about Iranian Nowrooz and Indian Holi by watching documentaries on Canadian television while I studied there.

Taking inspiration from that version of multiculturalism, my crew and I started documenting various Dubai neighbourhoods last year for My Neighborhood, a documentary series that aims to shed light, at least to us, on who really lives in this country and what their stories are. In the process, we were often unconvinced that the changing landscape of the country carries the imprints of a substitute national identity.

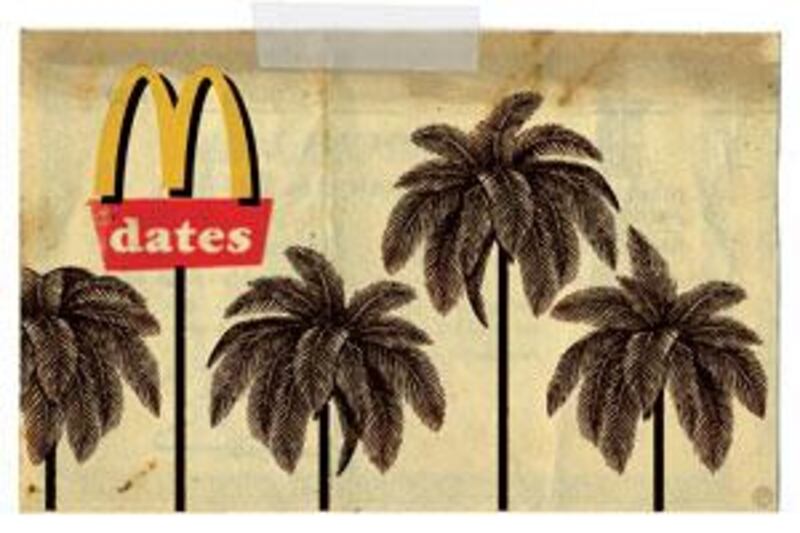

Dubai and Abu Dhabi do not take on Indian or English cultures despite the large number of expats from these regions. A capitalist ethos is drowning out our ethnic culture. This could also, of course, be argued in the UK and the US - although in those countries, communities are evidently more successful in balancing preservation. Perhaps we could learn from their example and this could be the best time for expats and locals to join efforts in preserving each other's heritage.

The history of locals and expats working together is many decades old, so this could just be another successful venture. But before that, I hope someone will do us the honour of a proper introduction. Mahmoud Kaabour is an award-winning filmmaker and the managing director of Veritas Films