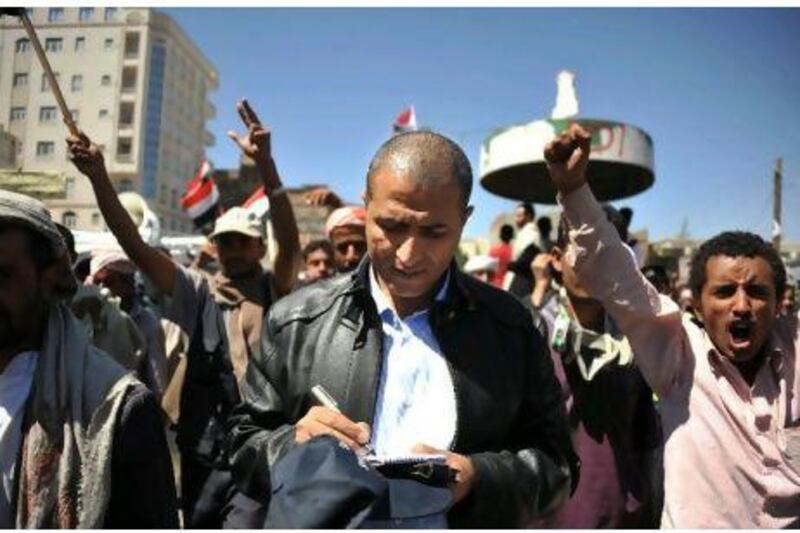

Mohammed Al Qadhi, a reporter for The National in Yemen, has been covering the uprising in the country since it began in January. Al Qadhi, 37, thought that the uprising to oust President Ali Abdullah Saleh would be as quick as those in Tunisia and Egypt. By summer, it was clear it would not be.

July and August

Some calm has returned to Sanaa, but life is difficult. Nowhere is that more evident than at petrol stations, where the tensions that linger just beneath the surface regularly erupt.

With petrol expensive and scarce due to the bombing of a pipeline in Marib province in mid-March, lines of hundreds of waiting vehicles stretch from petrol pumps down the street. Gunfights break out among frustrated customers.

I'm forced to take taxis or buy expensive fuel on the black market. I also send someone to get petrol for my Suzuki sedan, and he spends 10 days waiting at the station.

This is not uncommon. People wait in their cars until a fuel tanker arrives. They sleep in their vehicles and leave them unattended only to use the bathroom or fetch food.

In July, the oil pipeline is fixed and by early August, fuel is easier to obtain. Still, petrol prices don't drop because the increasingly cash-strapped government eliminates fuel subsidies.

The lack of mobility frays the nerves of everyone at home.

"Please dad, take us to the park. We're fed up," pleads my five-year-old daughter, Reema. My wife, Haifa, feels trapped too. We can't travel to Taiz to visit our families.

At the same time, chronic power outages that can leave us with only two or three hours of electricity a day make us feel even more claustrophobic.

With power supplies uncertain, we have to buy food fresh every day so it doesn't spoil. The mangoes my wife stores in the freezer go rotten.

September

It's back-to-school month, and I'm now faced with a familiar dilemma. Do I send my three daughters to school? My wife and I do so reluctantly, all the while worried about what happens if fighting breaks out again.

Sure enough, it does. On September 18, supporters of President Ali Abdullah Saleh kill 26 protesters in Sanaa, sparking more fighting between pro-government forces and soldiers who have defected.

Once a truce is called, I decide to go and see the area damaged in the fighting. Soon after I arrive, gunfire breaks out. I drive crazily from one street to another, finally settling in a place I think is safe. Then I hear gunfire from a sniper. I speed away again, driving the wrong way down a one-way street to escape.

The situation in Sanaa only worsens when President Saleh suddenly returns in late September from Saudi Arabia, where he has been convalescing since an assassination attempt in June.

The day after his return, more than 50 people are killed when Saleh loyalists raid the protesters' camp and a compound controlled by army defectors. Supporters of Sheikh Sadeq Al Ahmar, leader of Yemen's Hashid tribal confederation, fight on the opposition side.

As the conflict widens, my household expands.

My wife's sister, Enas, her husband and their three children move into our home because it is safer than theirs, which is nearer to the protesters' encampment. As the evening goes on, the shelling gets worse and I tell everyone to go to the basement.

Haifa and Enas start weeping and blaming me for refusing to leave the house. I go outside with my brother-in-law to see if the house has been damaged. Another shell passes over and hits nearby. We scurry back to the basement.

October

It's now impossible to predict what will happen each day. All semblance of routine is gone.

Some days I send my kids to school, other days I don't. There is no consensus among parents what to do, either.

A friend of my daughter, Maha, refuses to go to school, naturally prompting Maha to ask why we still send her and to question how much my wife and I care for her. "Aren't you afraid for me?" she asks.

The night of October 16 is the worst yet for us. Government forces bombard the neighbourhoods of Hasaba and Sufan, where the armed supporters of Sheikh Al Ahmar are dug in. They also target ex-government soldiers shielding the protesters and the headquarters of the First Armoured Division, which defected with its commander, General Ali Mohsen Al Ahmar, in March. The shelling is closer to our home than ever.

During the bombardment, Enas and I twice crawl from the basement to the kitchen to bring some bread and fruit to the others. Artillery shells whistle over the house and shake it when they explode. It's the most terrifying night of my life. I'm obsessed that we all might be killed, and I feel guilty that it will be my fault.

By the next morning, the shelling has stopped. Our kitchen window has been hit with shrapnel, a window elsewhere in the house by a stray bullet. Buildings in the neighbourhood are damaged; cars are smashed. We have no choice but to move into a hotel. I feel better that my family is safe, but I'm concerned about our house.

For Haifa and me, our home is our baby, and we're worried that it will be destroyed by a random rocket fired by a crazy soldier.

I hire a man to guard the house, though in many ways, of course, it's a fruitless gesture.

November

There's a lull in the violence. We are now back home. But still we are not able to travel to spend Eid with our families in Taiz because of the fighting there.

On November 2, clashes between Saleh forces and opponents there leave 16 dead and more than 40 wounded.

I find myself thinking about finding a job outside Yemen. Haifa used to object, but no more.

There is only so much my family can endure and I don't know where all this is going.

Neither the tribes, the opposition parties, the youth protesters nor the military defectors have the power to challenge Saleh's relatives and the regime.

I've been on a roller-coaster of emotions for 10 months. After Tunisia and Egypt, I was full of hope. Now I'm drained and tired. When I'm in a pessimistic mood, I'm sad for my country and worried that it could turn into another Somalia.

When I'm optimistic, I believe the international community will work some diplomatic magic. I believe that all of Yemen's feuding factions will sit down and agree on how to save the country after Mr Saleh is gone. Finally, I believe that everyone will see Al Qaeda as the enemy and drive them out of my country.

What keeps my pessimism from winning out is the strength I draw from the resilience and determination of the young protesters.

I don't necessarily agree with all that they stand for, but I admire them for persevering despite the beatings and bullets they have endured.

More than anything else, they keep my hope alive.