BEIRUT // Human rights activists are hailing last month's decision by Lebanon's interior ministry to allow citizens to petition for the removal of their religion from national identity cards, but fear the changes do not go far enough or could be temporary in the country's unsettled and often religiously intolerant political environment. Lebanon's government and political system remains deeply sectarian: top political posts, seats in parliament, civil service jobs and university slots are all overtly or subtly distributed according to sectarian patronage. While reformers have long clamoured for the country to break from its painful and religiously divisive past, every major political party continues to be focused around religious identity, weakening the overall ability of the government to reform, according to human rights researchers and experts.

"This is a step in the right direction but the government needs to take the next step and ensure that all Lebanese can have access to personal status laws that are not religiously-based and provide for equal treatment," said Nadim Houry, the senior researcher at Human Rights Watch. "Otherwise all Lebanese will continue to be forced to be officially members of specific religions and subject to their laws on key issues like marriage and inheritance."

Lebanon recognises 18 different ethnic and religious groups, which are allocated seats in parliament and civil service appointments according to their size and influence. Top political positions are also reserved for various sects: The prime minister is always a Sunni, the president a Maronite Christian and speaker of the parliament, a Shiite.The system has long been the source of religious and political tensions as the current ratios give far more influence to the Christian, Druze and Sunni communities compared to the much more numerous Shiite population.

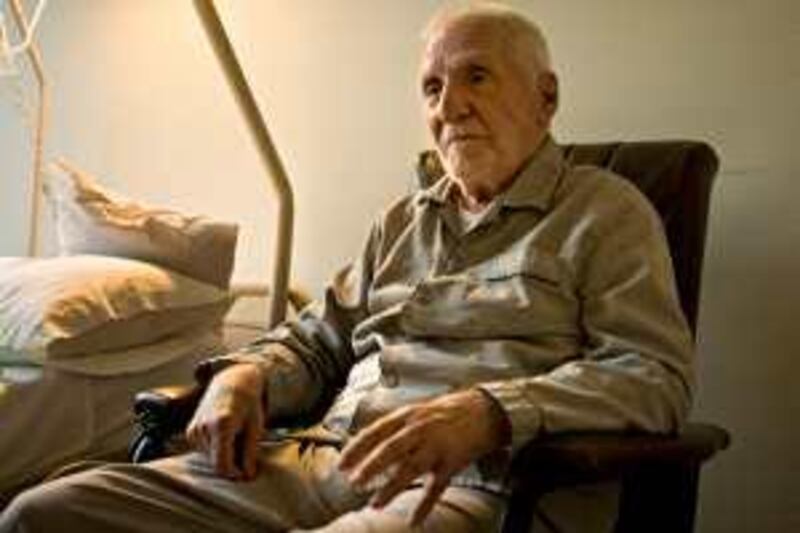

Lebanon's 1975 to 1991 civil war was in large part fuelled by Muslim anger towards the continued Christian dominance of the country's political system. The war saw thousands of sectarian killings, often made easier by victims having a clearly stated religion on their identity card. The push to remove such identification from the cards began in the most unlikely of places, with an elderly priest. Ten years ago, Bishop Gregor Haddad, 80, decided that the system was unjust and political rather than religious and began a campaign to remove religious sects from government documents.

"Crossing out my sect does not mean that I became an atheist or doubting in my God; no, I just want to be identified as a Lebanese only," said Bishop Haddad. "What we have to do now is convince Lebanese citizens that crossing out the sect from our cards does not mean that we are abandoning our religion. Nothing is wrong with a secular system that will give independence to the constitution from religion, and it gives politics and politicians' independence from religion. It is a step towards a just society."

Bishop Haddad has been working towards lessening sectarian tensions for more than four decades and more than half that time has seen Lebanon embroiled in often-violent religious disputes. "I have been an activist in the civil society movements since 1960," Bishop Haddad said. "I have always been trying with other activists to have a nonsectarian, non-violent Lebanon. I believe in secularism and it is the only way for salvation in our small diverse country.

"Ten years ago Talal Hossani and I started this campaign of crossing the sect of our records, in order to be identified as Lebanese people but not members of sects," he added. Mr Hossani heads the Civil Center for the National Initiative and was the first person to formally apply to have his records stripped of his religious identity. His early petitions were denied but with the arrival of a new unity government, the interior minister Ziad Baroud decided to approve the request as part of a bureaucratic reform effort.

One of Mr Hossani's activists is 24-year old Rasha Najbi. She calls this effort part of a critical fight to change the attitude of the Lebanese towards each other. "It's all about the freedom of choice, the freedom to be whatever we want," she said. "It's about how we want to be identified in our daily life. We are born in this country with colours: colours we didn't even choose. It is time for us to stop and think how we want to be identified. Being free from a sect gives me a civil character when it comes to dealing with bureaucracy, instead of being dealt with as a part of a sect or religion."

But compared to the deeply entrenched attitudes of the Lebanese population and government, which still refuses to recognise civil marriage, divorce, inheritance and child custody issues as anything but religious matters to be decided by the leaders of each sect, Lebanon continues to lag behind much of the world in respect to civil rights, particularly for women, who are often discriminated against by religious conservatives in family matters.

Human Rights Watch notes that even the United Nations has criticised Lebanon's refusal to put family law into a secular legal code, citing a 2008 call by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women that Lebanon "urgently adopt a unified personal status code which is in line with the Convention [Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women] and would be applicable to all women in Lebanon, irrespective of their religion."

But in a country that has seen religion frequently defeat civil activists, some supporters fear that after the June elections, changes to the government could set back their fight to be free of such designations. "I was happy to hear that the minister of interior Ziad Baroud has passed the law," said 23-year old Ahmad, who only gave his first name. "Now all I'm thinking about is the moment I will be free of the sect I'm registered in. I was telling my friends two days ago: 'Let's do it as soon as possible, let's benefit from the time of this current government'."

"We are not sure if the next government after the elections will have Ziad Baroud as minister of interior again. We might have someone else and most likely a backward sectarian minister of interior, and then we might lose the chance of being free." mprothero@thenational.ae