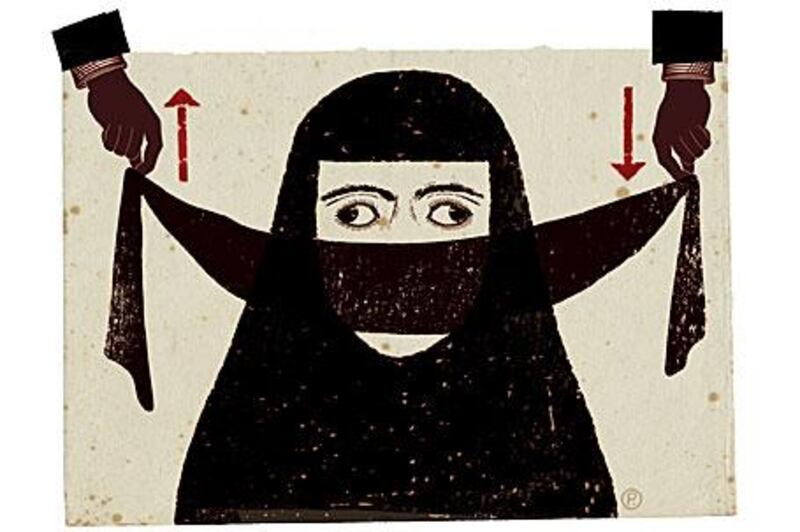

When does the head of Al Azhar agree with right-wing racist political parties in France and Italy, but disagree with the Kuwaiti Ministry of Islamic Affairs? When it comes to the issue of Muslim women and the veil. It is a subject that creates strange alliances, all with one thing in common - the self-appointed right to interfere in what a woman chooses to wear.

Sheikh Muhammad al Tantawi, the senior sheikh at Al Azhar, was visiting a girl's school when he told an eighth grade student to remove her face veil saying: "The niqab has nothing to do with Islam and it is only a mere custom. I understand the religion better than you and your parents." At his insistence, she removed the veil. He said: "You are actually like this [ugly]. What would you do if you were a little bit beautiful?"

It surprises me that a scholar and role model, a man with public influence, responsibility and care of duty, feels that he can use public intimidation on a young woman, and that he has a right over a woman's clothing, defining and commenting on her family, looks and her intelligence. Four women elected to the Kuwaiti parliament found themselves at the opposite end of another discussion about veiling - an insistence that they should cover in order to be admitted to fulfil their constitutional roles.

Their election came after Kuwaiti women received full political rights in 2005. Since two of the women choose not to cover, an ultraconservative MP asked the ministry of Islamic affairs and endowments' Fatwa department if Sharia obliged women to wear the hijab. When the ministry agreed that women were indeed obliged to do so, there was a movement in parliament to impose hijab on the national assembly's female members, stating that it was incumbent on women in parliament to subscribe to Sharia.

Despite the obvious difference with Sheikh al Tantawi's views, they share one thing in common - the humiliation of women in public space, and their reduction to what they wear rather than who they are. The constitutional court has upheld the right of the women to remain uncovered if they choose. We can hope that this will drive home the importance of what the women have to say, and the value they will bring to the political process, rather than reducing them to their clothing, as though they were vacuous Barbie dolls.

The French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, picked out the veil as an issue of primary concern to the French public even though only 367 women wear it, out of a population of 62 million. Silvio Berlusconi, the Italian prime minister, supports a similar ban. There has been a ban on the headscarf in French schools and universities since 2004, not unlike a similar ban in Turkey, which labels the headscarf as contrary to the country's secular principles.

Wherever you are in the world - Muslim country or otherwise - the issue of veiling is a hot topic. Muslim women are bundled into a single-issue "problem", and that issue is the veil. That is the problem with Marnia Lazreg's recent book Questioning the Veil. Lazreg, an American academic with Algerian roots, lays the problems that Muslim women face at the feet of the veil. She claims to systematically demolish every reason that Muslim women give for wearing the veil. She highlights issues such as sexual harassment, men defining women's bodies, gender politics in the workplace, the anonymity of women, men wielding full control over women and women as the vessels of male honour.

She then draws the tenuous conclusion that the veil lies at the heart of all these issues. I disagree. Even if the veil was removed, these underlying problems would still be rampant. The veil is the wrong symptom she is trying to treat. What we should be doing is tackling the underlying causes. She also adds that, if a woman truly believes that wearing a veil is the right thing to do, and she has made an informed choice to do so, then we should accept her decision. Simply put, we do not need to force women to veil, nor do we need to force them not to veil - what we need is education and free choice.

This is simplistic single issue politics at its worst - offering a bland and unintelligent analysis of the very real problems Muslim women, as well as society at large, are all facing, grouping them together as caused by the veil. This obsession with the veil as the source of contention is illustrated by the constant stream of news and opinion pieces with titles like "uncovering Islam", "behind the veil", "beneath the veil" and "under the veil". We do not need to get under the veil, we need to get over it.

If Barack Obama, the US president, believes that a nation torn apart by race issues can become a post-racial society, then there is legitimate hope for a post-veil society. It is a society where a Muslim woman can get on with the task of living her life - in education, employment, security and safety in the family, private and public spheres. It is a society where who she is, rather than what she wears, is her definition and her contribution.

In such a society, the veil is no longer her only definition, no longer even her primary definition. This is a society where a woman's choice to veil or not to veil is her choice and hers alone. There are those who will say that this article is contributing to the monolithic obsession with the veil. In some ways they are right, it is yet another article added to the thousands dedicated to this subject, when they ought to be focusing on other issues.

Yet, curiously, it is veiled Muslim women themselves who raise this point, fed up with seeing themselves portrayed as nothing more than the veil they wear. I feel it too as a Muslim woman, yet I feel compelled to write about it in order to create a movement to get over it. I have to keep writing about it till the Sarkozys of the world stop women gaining citizenship because of it. I am driven to keep highlighting the Marwa Sherbinis of the world - a woman stabbed in full public view in a German court, at the hands of a man who hated her for her headscarf.

It may shock both liberals who oppose covering of any sort, as well as traditionalists who would enforce mandatory veiling on women, that Muslim women more often than not have other priorities, and also want something other than their clothing discussed. For example, in countries like Afghanistan and Iraq, where "saving" Muslim women is high on the list of justifications for invasion, the discourse on veiling is low on the list of women's concerns.

Security tops their needs, something that the "liberating" forces have denied them. We need to get past the veil, and into the business of living - education, employment, security, personal law and civic and political participation. Aseel al Awadhi, one of the women elected to the Kuwaiti parliament asked: "Why do only women have to comply with Sharia law and not men? This is, by itself, discrimination." Her subtext: veiling and visible religiosity are used as gatekeepers and excuses to exclude women from public and political discourse - that it has nothing to do with religion, and everything to do with power.

Love In A Headscarf, by Shelina Zahra Janmohamed, is published by Aurum Press.