New York was a city transformed after World War II. Towers soared into the Manhattan sky, the United Nations made the city its headquarters, and by the late 50s, the Big Apple began to eclipse London as a major financial centre.

Hopes of a similar transformation were high in Abu Dhabi on the other side of the world. Despite striking oil in 1958, a visitor to the town would have struggled to notice any change to how people lived. Life remained desperately hard, with most houses constructed from simple palm fronds. There was not a metre of concrete road anywhere in the emirate.

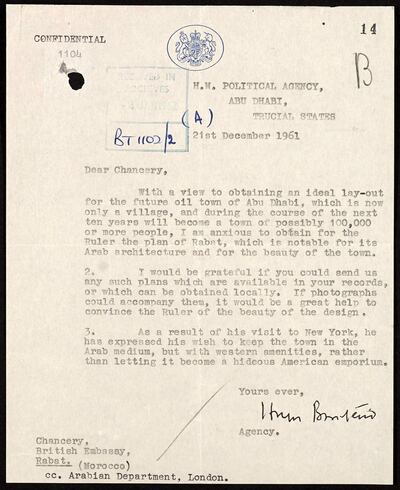

But a simple letter, typed on yellowing paper and sent on December 21, 1961, reveals that Abu Dhabi was not looking to the Big Apple for inspiration. Now available to read online for the first time as part of the Arabian Gulf Digital Archive, the letter was written by Hugh Boustead, the British political agent in Abu Dhabi, to its embassy in Morocco. He wrote that Sheikh Shakhbut, the Ruler of Abu Dhabi, had recently visited America and it made a big impression. But not what you might think.

“As a result of his visit to New York, he has expressed his wish to keep the town [Abu Dhabi] in the Arab medium … with western amenities, rather than letting it become a hideous American emporium,” he wrote.

It is not clear if Sheikh Shakhbut used those exact words but in the letter, Boustead requested town plans of Rabat which could influence the planning of Abu Dhabi as an oil town for 100,000 people – up from the few thousand that lived there at the time.

“With a view to obtaining an ideal lay-out for the future oil town of Abu Dhabi - which is now only a village - I am anxious to obtain for the Ruler the plan of Rabat, which is notable for its Arab architecture and for the beauty of the town,” he writes. “If photographs could accompany them, it would be a great help to convince the Ruler of the beauty of the design.”

Not much evidence survives of Sheikh Shakhbut’s visit to New York and Boustead’s letter is the only reference to it in the archives. Boustead’s bosses in Bahrain picked up on the positive noises regarding development coming from Abu Dhabi but a British report later that month warned against underestimating Sheikh Shakhbut who was renowned for micro-managing budgets and not wishing to spend too much money.

“[Boustead’s] news is encouraging and I much hope that it represents the first real step in getting planned progress in Abu Dhabi under way,” it noted. “It would be as well, however, to sound a word of caution: the Ruler is very astute and is unlikely to let anyone make a quick fortune out of him.”

At the same time as Boustead was asking for plans of Rabat, Sheikh Shakhbut asked John Harris to drawn up the first town plans for Abu Dhabi. The British architect is more known for his work in Dubai, including two city master plans, the Trade Centre and Rashid Hospital, but less is known about his work in the capital. Sheikh Shakhbut told Harris to start work in 1960 and over the next two years, he drew up the very first plans for a modern city.

He was starting from scratch. But Harris did not want to erase the old town. The souq, mosques and Qasr Al Hosn were retained but all traditional palm frond houses faced the wrecking ball. Residential neighbourhood units would replace these old homes, with baqala-esque shops to cater for the residents. Harris eschewed the grid system that we have today - the only straight roads were in the city centre, while roundabouts appeared at key intersections. Parking spaces for 10,000 cars were also included, while the plan also advised a huge palm tree-planting scheme.

But the earlier hopes that development would now start in earnest were short-lived. It was clear that Sheikh Shakhbut resisted change and was loathe to spend money. There was also some suggestion of competing influences among British who were vying for the building and designing contracts. But in March 1963, a note from the political residency in Bahrain alluded to new and separate plans for the city which Harris had agreed to co-operate on. This did not bode well for Harris.

“We must now await the production of the overall development plan to see what is involved and whether, as we hope, some or all of Harris' streets can be fitted in to the new and much larger plan,” it said.

It is there that the file ends. The archives do not precisely reveal what happened to the Harris plan or the Rabat influence. But planning a new Abu Dhabi would go through several more tortured phases and years before the city we know today started to emerge.

UAE National Archives

A treasure trove of archives went online this year. Treaties, letters, maps, images and videos shed light on more than 200 years of life in the Arabian Gulf set against the backdrop of war and the search for oil.

The portal, called the Arabian Gulf Digital Archive, is the fruit of two years of work by the UAE and UK. Most of the files are from the UK’s foreign office and provide a fascinating glimpse into the way the British tried to keep a grip on the Middle East, the poverty here following the Second World War and how oil transformed the region.

But the huge archive is also littered with vignettes, diplomatic asides and colourful flourishes that bring these yellowing and faded documents to life. It would take months to pore through them all but here is a small taste of its vast riches.