ABU DHABI // The link with the desert is an unbreakable one for the Bedouin, even those who have settled in the cities.

"We need to feel the sand between our toes on a regular basis or we feel something is missing," says Mohammed Al Khateri, a member of the Khawater tribe, one of the UAE's largest, with links to Bedouin across the Arabian Peninsula.

Mr Al Khateri, now in his fifties, lived the nomadic way as a child, among the camels and "adventures" of the open desert.

The family often travelled across the desert trails to Saudi Arabia and beyond, finally settling in Ras Al Khaimah about 40 years ago.

"It was a very difficult life. We were often hungry but anyone who grew up in the desert can't forget it," he says.

Dr Sulayman Khalaf is full of admiration for that connection with the harsh, unforgiving land, and for the lifestyle and moral codes of the nomadic tribes.

"There is something very romantic and adventurous about the Bedu and their way of life," says Dr Khalaf, an anthropologist at the intangible heritage department of Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority.

"Their honour, their pride, their generosity, and their amazing survival skills and traditions in the harsh desert - you can't help but admire them."

For more than 30 years he has studied and published works on Bedouin groups, and documented the changes in their way of life after the discovery of oil and their settlement in towns and cities. He will share his knowledge in a panel discussion tomorrow at New York University Abu Dhabi.

"Bedouin life as an economic mode of life has changed dramatically and ceased to exist in many parts of the Arab world," Dr Khalaf says.

"What remains revolves around some of their cultural traditions and their tribal links in terms of remaining connected to their ancestry through tribal names, and the preservation of certain social practices, like hospitality customs and traditions and keeping marriages preferably within tribal boundaries."

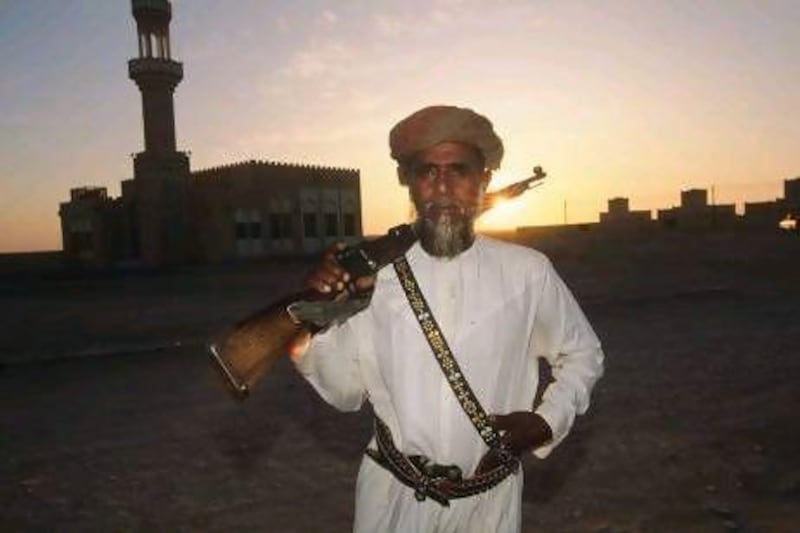

The nomadic way is associated with the Arab world's greatest and oldest poetry, and most noble heroes.

These images live on in the minds of current generations and those few who have made it their mission to document the lives of Bedouin groups across the Middle East.

Dr Khalaf has his roots in the Afadla tribe, a shepherding and farming tribe from north-east Syria. He is familiar with the broad changes in the Bedouin way of life over the past 50 years.

"Being a member of a tribe gives you a sense of identity, and genuine historic links to a community and a place," he says.

"People tend to lump together all the different tribes as Bedu, but it is usually the nomadic, camel-herding, pastoralist tribes that lived in the desert that are defined as Bedouins.

"The camel tribes are known for their amazing survival skills, adaptation traditions and poetic-expressive culture."

He says Arabian horses were mainly owned by merchant and royal families in the Gulf region.

Dr Khalaf explains that the Bedouin tribes of Syria, Jordan and northern Iraq have links with the northern Najd tribes of Saudi Arabia, while the tribes naturalised in the UAE come mainly from Yemen.

He says use of tribal names in the Gulf has been revived in the past few decades, in part to preserve each tribe's social identity within the expanding urban environment and the large number of expatriates.

"There is a revived interest in everything related to the Bedouin, especially among Arabs themselves," says Dr Nathalie Peutz, an anthropologist and assistant professor of Arab crossroads studies at the university.

Dr Peutz, who has worked with Yemeni pastoralists for more than eight years, will moderate tomorrow's panel.

"Very few people in the Middle East today still live as Bedouin in the sense of a nomadic pastoralist lifestyle," she says.

"Bedouin-ness is now associated largely with an identity and a heritage that can also be commodified through tourism."

But having Bedouin roots means different things to different people and the significance of the term has changed over time.

"For an Arab to say he is from a Bedouin family, it is like saying, 'Look, this is where I am from, a group of people known for their generosity, their honour and values'," Dr Peutz says.

"Globally, heritage is becoming more important to people because with the move toward a more global economy and culture, people want to have something that distinguishes them from others.

"We as citizens of modern states are organised along national lines, and governments control human mobility through passport and borders.

"So this notion of a free, roaming, nomadic life strikes a romantic chord with us."

Being Bedouin: Past and Present takes place at New York University Abu Dhabi's campus in the capital tomorrow from 6.30pm to 8.30pm. Apart from Dr Khalaf, speakers include Dawn Chatty of Oxford University and AbdAllah Cole from the American University of Cairo.