It was 1969 when a 28-year-old German historian and researcher stepped across the threshold of the formidable Qasr Al Hosn to browse through a collection of books at a small office that became the National Centre for Documentation and Research. Little did she know her decision would change her life forever.

"I wanted to start researching and reading up on what was back then the Trucial States," recalls Frauke Heard-Bey.

At the time, she had published her doctoral dissertation on the fate of Berlin during the political upheavals following the First World War. Now she lived with her British husband David Heard, a petroleum engineer, in Abu Dhabi, after their marriage in 1967. "It was a completely new world to me, and I wanted to know more about it," she says. And so, she took the first steps into understanding the Emirates by entering Qasr Al Hosn.

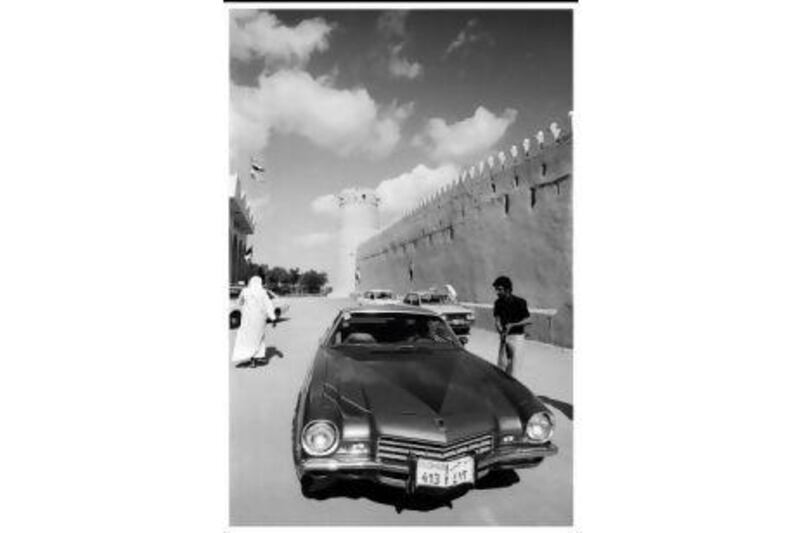

She remembers going through the front gate on that first day, where an armed guard stood against a thick wooden door, studded with massive nails and within it a smaller door, known as Al Farkha.

Beyond was a narrow pathway that ran past the oldest watchtower, the point of birth of Al Hosn around 1760. She walked across a majlis room once dedicated to foreign delegates then continued along courtyards to one of two small villas that were added by Sheikh Shakhbut in the early 1960s.

One villa housed the centre and the other, the head of the government, the diwan, where the founding father Sheikh Zayed had an office, as did his right-hand man and minister of foreign affairs, Ahmed Al Suwaidi.

In the large L-shaped room of the centre were a few desks, a surprising number of books and three men at work: Muhammad Morsy Abdullah, the director and an Egyptian historian; Ahmed Mansour, an Emirati; and Ali Nasr Al Hajari from Oman.

Ali, an Iranianin local dress, was ready to serve coffee to visitors, while on the first floor the government's telegraph room was manned by two Indians.

That day Heard-Bey met Abdullah, who later received his doctorate from Cambridge University. He asked how he could help her.

After asking to read the material in the archive, she was told: "You are welcome."

There were about a 100 books and 50 articles from academic journals and other sources relating to the Trucial States and other parts of the Arabian Gulf and Peninsula. "I had found a completely unexpected treasure hidden in this old fort," Heard-Bey recalls.

"I noticed that some of the visitors to the other villa who had drifted into the centre's office asked to borrow a book or two to read during their stay. But they seemed to disappear.

"So I suggested that this library should be catalogued and organised, before expanding it to include everything on the Arabian Peninsula," she says. Making these observations to Abdullah, he replied: "Why don't you do that? Organise it for us."

Within three months, Heard-Bey was hired to archive and take care of the collection, with a salary so minimal she cannot remember what it was.

"I made connections with other libraries, such as the Library of Congress during a visit to Washington, and slowly helped to established a rare and comprehensive collection of the books and periodicals we needed," she says.

For the next 29 years, Al Hosn became Heard-Bey's second home. The centre itself moved several times during different phases of a decade of renovations to the fort, with Heard-Bey eventually residing in almost every corner of Al Hosn at some point. The centre moved out of Al Hosn in 1998 to its current location next to the Sharia Court.

In the 1980s, the rooms near the gate served to exhibit the centre's work, as a museum of photos and documents from the formation of the UAE and as a base for the Natural History group, including a lab for their work.

"While I was the only European - and a woman - to go in and out of the fort on a daily basis, I tended not to venture out to explore other corners of the fort, as parts of it were the quarters for the guards and falconers and I wanted to respect their privacy.

"But we did talk, in particular when my Arabic improved. Some of the guards joined the regular police later and when I met them somewhere, such as for instance at the border post between Abu Dhabi and Dubai, we greeted each other as long lost friends," recalls Heard-Bey.

Sometimes visitors would be Bedouin men, dropping in for coffee and a chat, posing questions to the blonde academic who seemed out of place. On another occasion it was Yasser Arafat, the late Palestinian leader, who was visiting Sheikh Zayed next door in the early 1970s. "He was a very friendly chap. He, like many other visitors, probably didn't understand what I was really doing there in the middle of the fort," she says.

Large parts of Al Hosn were administrative offices for the Abu Dhabi Rulers Court. "Whoever came to Hosn eventually ended up visiting our centre, partly to sit down and have coffee as they waited for their papers to be sorted," she says. "It was never dull at Hosn. There was always something happening or someone important visiting."

When the centre moved to the east wing of the palace and an air conditioning system was put on the roof that included chilled water, it was common to see men sleeping up there.

"We had a leakage once, into our office, and the specialist who came to check what the problem was said that someone had opened the tap on top to use the water and didn't close it up properly," she laughs. "The tap was made more difficult to turn after that so we didn't end up with floods in our office."

Another time, Dr Heard-Bey remembers exploring Al Hosn with her son, Nicholas, then 4, and his friend Christopher, ending up in the kitchens. "The kitchen was always in use - they would cook there for feasts taking place at the Manhal Palace," she says. "My son ended up climbing into one of the large witchlike cauldrons. These were good times."