Within minutes of Ashton Arbuckle's birth at City Hospital in Dubai, an obstetrician was collecting blood from his umbilical cord and placing it in a sterile container.

Three hours later the refrigerated package was in the hands of a medical courier and on its way to the UK to be placed in a cryogenic storage unit for the next 25 years.

Why? Because in the future the stem cells in baby Ashton's cord blood could save his life and those of any siblings, his parents and even strangers.

Umbilical cord blood is a rich source of stem cells, which are considered the building blocks of the body. These "master cells" have the ability to self-renew almost indefinitely and to develop into cells with specialised characteristics that can treat dozens of conditions including cancer and blood disorders.

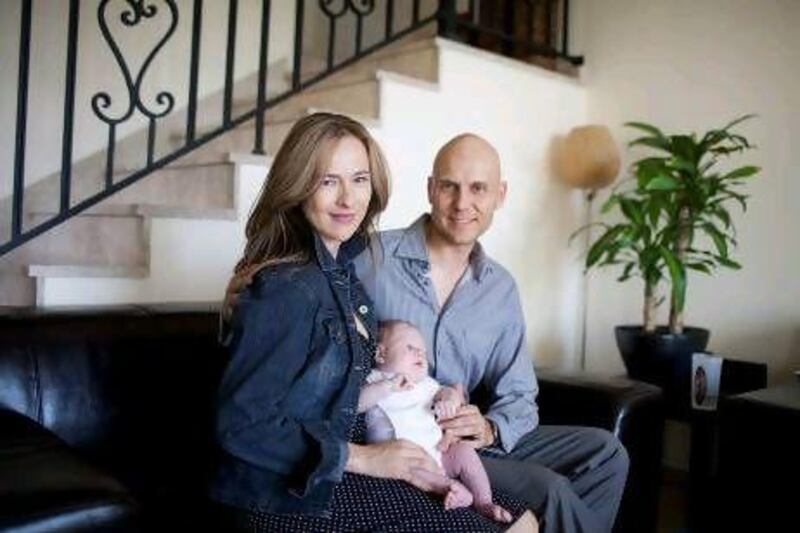

Regenerative treatment of this nature is being considered the future of medicine and while its wider potential to cure is still being analysed by scientists across the globe, for Daryl and Angelique Arbuckle, the parents of seven-week-old Ashton, the decision to spend almost Dh13,000 storing their son's cord blood was a simple one.

Last year Mr Arbuckle, 38, had a benign brain tumour removed and while he admits he does not fully understand the science behind stem cell research, he is happy to do anything to safeguard his son's health.

"Medically I've been through quite a heavy experience. This is the most advanced type of care you can give to your child as it could help him in 10, 20 or even 70 years time," says Mr Arbuckle, a South African and an executive director for Ernst & Young in Dubai. "It's like an insurance policy. With my current condition life-insurance companies won't touch me, so sometimes if you leave these things you get yourself into a position where you can never do anything about it."

Insuring against your child's future is certainly one way of looking at the collection of cord blood, but the potential of stem-cell therapy is much greater than that.

The first successful cord blood transplant to regenerate blood and immune cells took place in France in 1988, on a six-year-old American boy suffering from Fanconi's anaemia, using the cord blood cells of his sibling. That boy is now in his late twenties and is a father himself.

Since then more than 30,000 cord blood stem-cell transplants have taken place on patients suffering from cancers such as leukaemia and lymphoma, blood disorders such as anaemia and thalassaemia, and genetic conditions. Scientists are closing in on breakthroughs on a monthly basis and lauding the cells' potential to treat, and even cure, some of the world's most prevalent medical conditions.

"It's a growing concept," says Darryn Keast, the regional manager for MedCells, the company responsible for collecting Ashton's blood. He has also stored the cord blood of his own three children. "Since 2010, cord blood has surpassed bone marrow as the transplant of choice because there is no pain or risk. Because more people are storing, more of these samples are available, whereas with bone marrow there are challenges such as not being able to find a match."

The growth of the industry is reflected in the increasing number of cord blood-bank companies in the UAE - up from only two in 2006 to at least seven now, with more around the region. While some store the blood in the UK, others do so in India, and there are options to keep half the sample for the family and donate the other half to a public cord blood bank, making it available to anyone with diseases that cord blood cells are approved to treat.

In a research lab at United Arab Emirates University in Al Ain, Dr Sherif Karam, a professor of anatomy and cell biology, has been quietly plugging away at stem-cell research since 2001.

He is exploring the link between adult stem cells, which, though hard to identify, can be isolated from almost any tissue in the body, and stomach cancer - the second deadliest cancer in the world - to see whether stem cells play a role in originating cancer. Dr Karam is also investigating the factors that control gastric stem cells' ability to self-renew.

Believed to be the only academic carrying out stem-cell research in the UAE, the Egyptian scientist first started working in this field in the 1980s in the US, making his presence in the UAE even more significant because he is passing his knowledge on to young Emirati scientists, some of whom have already published papers on their work in international journals.

"We had an Emirati dentist from the Boston University Institute for Dental Research in Dubai Healthcare City working in my lab as part of his master's degree. He was able to isolate dental stem cells from different regions of the tooth, to maintain their growth and induce their differentiation in the lab. He is now studying for a PhD in Boston and I anticipate he will come back with a lot of expertise. Those kind of individuals will be the driving force for stem-cell research in the UAE."

Dr Karam believes it could be as little as two years before a stem-cell research centre is set up here. With the region's access to bigger funding pools and the imminent increase in the number of research labs locally, there is huge potential for the UAE and the wider region not only to join the stem-cell research race and find cures for diseases prevalent in local communities, but also, perhaps, even to lead it.

"This region has the funds and the facilities and there are many Arab scientists abroad who would be willing to come here if they see there is a facility and they can do whatever they do abroad. I think administrators can attract such scientists," says Dr Karam.

For a stem-cell centre to be established in the UAE, Dr Karam, who has his work monitored by two ethics committees at UAEU and Tawam Hospital, says the government may have to introduce policies surrounding more controversial areas of this research, such as embryonic stem-cell research, which does not take place here.

Guidelines for this have already been established in Qatar by the National Research Ethics Committee, and fatwas issued by the Islamic Jurisprudence Council of the Islamic World League in 1997 and 2003 approve embryonic stem-cell research for therapeutic and scientific research purposes, if obtained from permissible sources.

"Research and experiments in induced pluripotent stem cells and mouse and human embryonic stem cells are being conducted in the Middle East, whether here at Weill Cornell in Qatar, in Saudi Arabia or in Iran," Dr Jeremie AR Tabrizi of Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar told the Qatar International Conference on Stem Cell Science and Policy in March. "This is because the ethical issues of stem-cell research have been clearly addressed in Islam."

He added: "The establishment of a collaborative stem-cell network throughout the region will lead to greater disease-targeted research, which is not currently possible with individual, private investment initiatives."

While the potential for regenerative medicine seems boundless, for now the real issue seems to be ensuring that the general public, and the decision makers who will fund the research, know this type of science actually exists - something the new father, Daryl Arbuckle, agrees with.

"Not one doctor advised me about storing cord blood. I just told the doctors, who nodded their heads and said: 'We'll do what needs to be done'."