The World Health Organisation has conceded that Covid-19 may be transmitted through clouds of virus lingering in the air.

The admission has huge implications for preventing the resurgence of the pandemic as travel restrictions are relaxed.

But what sparked the re-think? Here, The National explains the latest.

Open letter

In an open letter published earlier this week, more than 200 scientists called on the WHO to recognise that the coronavirus can be spread by clouds of tiny droplets or "aerosols" which linger in the air.

The experts warned that the WHO’s current guidance – which stresses hand-washing, social distancing and wearing face-masks – assumes the principal infection route is from much larger particles, which quickly disperse and do not travel far.

According to the scientists, the standard precautions must now be backed by ways of controlling airborne transmission as well.

So what should be done to tackle the threat?

According to the scientists, the risk can be reduced through effective ventilation using clean outdoor air, especially in the workplace, schools, hospitals and care homes.

They also call for airborne infection control measures, such as air filtration and treatment with ultraviolet light.

In general, people should avoid crowded situations on public transport and public buildings. Some experts believe the threat also requires the use of higher-quality face-masks.

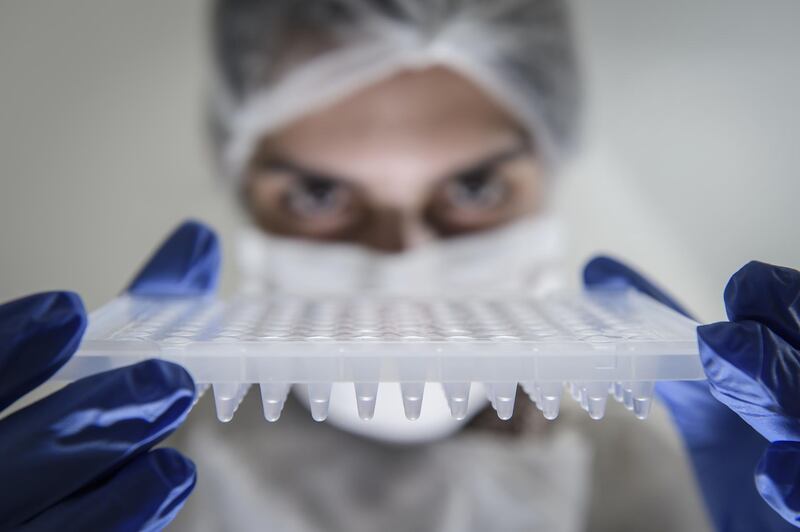

What is the evidence?

According to the scientists, studies of similar pathogens – including the Mers coronavirus – gives “every reason to expect” Covid-19 can be spread by aerosols as well as droplets.

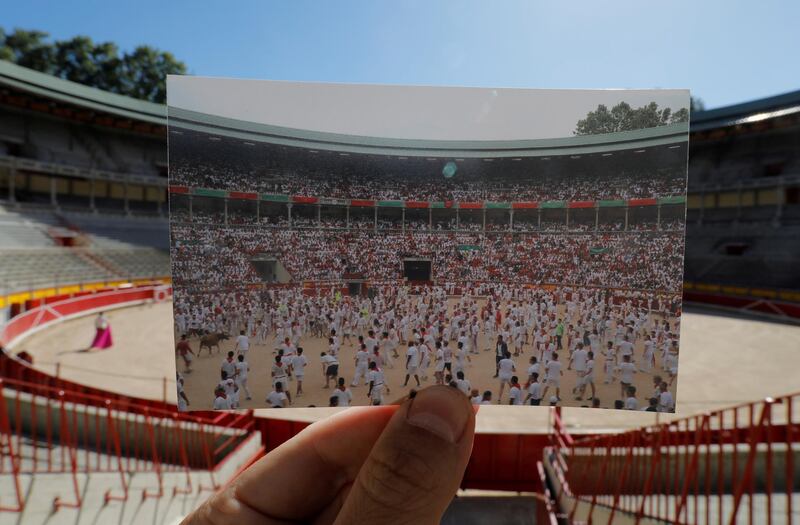

They also point to studies of outbreaks in enclosed spaces where people never came into direct contact. Such incidents prompted Japan to launch the “3Cs” programme, warning the public to avoid “closed, crowded spaces with close contact”.

Public health experts think this has played a key role in keeping Covid-19 deaths in Japan below 1,000, despite relatively lax controls.

Is the WHO going to change its advice?

The WHO already accepts airborne transmission is a threat – but only to health professionals exposed to virus-laden aerosols while treating patients.

Now it has conceded the risk of the general public being infected by airborne transmission “cannot be ruled out”.

Even so, its officials insist the evidence is “not definitive” and “needs to be gathered and interpreted”.

The scientists warn, however, that the risk is now “of heightened significance”, as countries move out of lockdown.

Their concern reflects the fact that delay in taking action leads to a disproportionate increase in the numbers of cases and deaths.

Why is the WHO dragging its feet?

While insisting more research is needed, the WHO’s response is thought by some to reflect concern the extra measures will be beyond the resources of many countries.

However, according to Professor Julian Tang of the University of Leicester and a co-signatory of the letter, if the WHO includes the threat in its official guidance, this will help release aid to such countries.

“If it is not included, then ironically, there will be no airborne precautions taken and the virus will just keep spreading among some of these same countries where their healthcare systems can least cope with it”.

What happens next?

The WHO says that it will clarify its position on the public threat from airborne transmission of Covid-19 “in the coming days”.

Such clarifications have become a feature of the WHO's role in the pandemic over recent weeks. Last month it bowed to pressure and reversed its long-standing refusal to endorse the use of facemasks by the public, while a key official was forced to retract her claim that people without symptoms very rarely infect others.

With many countries having to re-impose lockdowns following the failure of the standard risk control measures, the WHO has to make the right call on airborne transmission.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Professor of Science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK