Earlier this month, Tropical Storm Hubert careened into the island of Madagascar, killing an estimated 36 people and rendering approximately 38,000 others homeless. Over the next few days, a smattering of the world's newspapers took note of the disaster in terse 100 or 200-word newsbriefs. The United Nations set about coordinating relief efforts on the ground, but reported that landslides had cut off large portions of the island from rescue and damage-assessment crews. A week after the storm, much of Madagascar was not only struggling back to life, it was still in the dark.

This Monday afternoon, Andrea Bersan - a bald Italian man in sleek rimless glasses and a well-tailored suit - was attending a trade convention in Abu Dhabi when his BlackBerry lit up with a new message. Bersan works for DigitalGlobe International, one of the world's leading purveyors of satellite imagery. "I just received an e-mail," he said, brandishing the screen of his PDA to a couple of fellow convention-goers. "We got notified of Tropical Storm Hubert, so we're collecting over that area now."

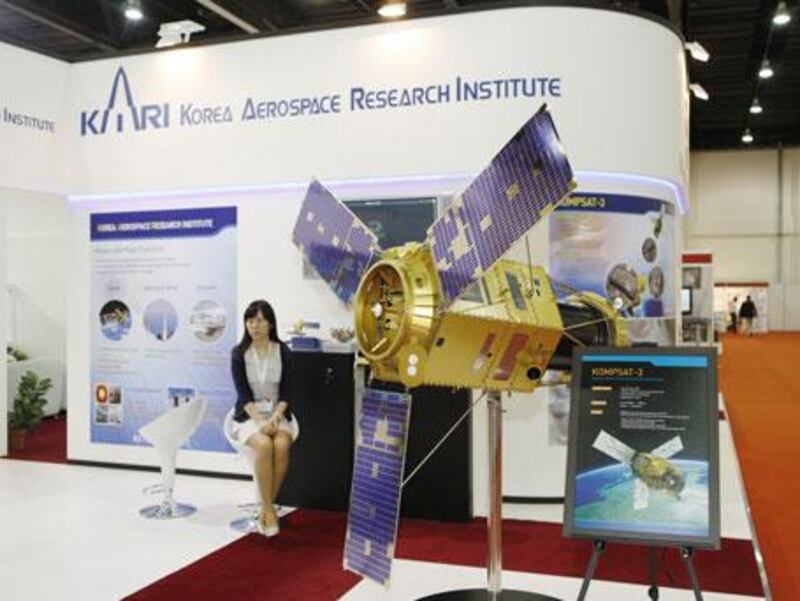

By "collecting", he meant that one of DigitalGlobe's three satellites was hurtling over the Indian Ocean, capturing high-resolution images of the disaster zone - such that one pixel of data would represent 50 square centimetres of ground area - at a rate of up to 700,000 square kilometres in 24 hours. "We can do half of Europe in one day," he said. Bersan was standing in his booth at Map Middle East 2010 - an exhibition on "geospatial information technology" - surrounded by large-scale models of satellites, surveying equipment, images of surveillance aeroplanes, unmanned aerial vehicles and computer interfaces. Tellingly, there were very few plain old maps on display. That's because geography in the age of remote sensing and information technology - far from having been rendered irrelevant, as some web utopians used to idly suggest - has launched into a brave, powerful and sometimes unsettling new world.

Today, insurance companies use "before" and "after" satellite images and aerial photography of disaster zones as a check against insurance fraud. The German government uses aerial 3D images - which make it possible to calculate volumes and other measurements on the earth's surface - to ensure that rubbish companies aren't trying to sneak too much material into their landfills. An American company called Spatial Networks has toyed with the idea of outfitting mobile billboards with GPS sensors and special face-recognition cameras, allowing marketing firms to actually count the number of eyeballs viewing their ad as it moves around town. And in Israel, one company used aerial 3D images to produce software for placing snipers in a battlefield; the resulting program showed which positions in a landscape afforded the widest field of vision. The same software was then repurposed for civil engineers and used to predict black spots in mobile phone networks."It started with a military application," said an engineer at the exhibition, "like most things."

But the power of all this new geographic information isn't only in the hands of Big Brother, so to speak. Ten years ago, if a layperson ever glimpsed satellite imagery of the earth's surface, chances are good it was in an action movie - the kind that featured densely plotted espionage and heavily accented villains. That made sense in a way, because companies like DigitalGlobe mainly sold their satellite pictures to various militaries. But today those images are available to just about anyone - including ordinary users of Google Earth, Nokia and the occasional video game.

"You're in Chicago, right Dr Rao?" asked a woman a few booths over from DigitalGlobe, addressing a South Asian man stretched out in a black plastic chair designed roughly to imitate the cockpit of a fighter jet. Holding a controller between his legs and staring up intently at a large plasma screen, he was piloting a flight simulator game called Tom Clancy's Hawx. Dr Rao - R Ramayanam Rao - works for GeoEye, one of the other major satellite imaging companies. He was flying a simulated F16 over an image of Chicago derived from one of GeoEye's satellites. After squeezing off a few rounds of machine gunfire into the air, he accidentally crashed into the suburbs. "Now we're going to Rio de Janeiro," he said defeatedly.

But of course, flying a virtual jet over a satellite image is at best a diverting way of putting geographic power in the hands of the people. Google Earth - which "crowd-sources" much of its map information - has shown that plenty of ordinary web users are interested in doing more with geographic data. But helping the public to think geo-spatially doesn't always come easily - especially in societies where the study of geography has been given token treatment. "The struggle we have," says Anthony Quartararo, the CEO of Spatial Networks, "is educating people about geography."

Back in the early 1990s, when he was a young geographer, Quartararo worked for a rural farm bureau in the United States, performing laborious surveys of arable land to make sure farmers were reporting their acreage accurately - and paying enough taxes on their crops. "You had a big aerial photo," he says. "You put a piece of tracing paper over it and drew the coordinates with a special pen. Then you'd put that up into the digitising board and digitise it."

"It's amazing how far we've come," he says. Today Quartararo sells a product called Geodexy, a simple software that allows people to quickly collect data in the field using nothing but an iPhone or BlackBerry. The GPS sensors on the phone instantly give whatever information you're collecting - whether it's bird sightings, political canvassing data, fire hydrant inspections, or parking violations - a geospatial signature. "There's nothing you would do that doesn't have a latitude and longitude attached to it," he says. It isn't just destiny. These days, Quartararo says, "geography is the science of everything."