ABU DHABI // Najieb Khoory's company grew 3,500 tonnes of vegetables on his farm in Ras Al Khaimah last year.

But no longer. This year, he will grow just 700 tonnes on his 25,000 square metres. The rising costs of water, electricity and labour have forced him to scale back production of strawberries and high-value crops such as iceberg lettuce, celery, leeks and broccoli.

He is one of a growing number of farmers who say they have learnt the hard way that food crops are neither a sustainable nor profitable business in the UAE.

The official view, though, is that farmers' problems are rooted in mismanagement.

"We are not an agricultural country," Mr Khoory asserted. "We don't have the basics of agriculture, which are water, soil and climate. Water needs to be desalinated, soil isn't used in hydroponics and the climate has to be controlled through greenhouses.

"In the past two years, electricity [costs] more than doubled and labour costs increased by 80 per cent - from my 500 labourers, I now have less than half. I don't see any future for agriculture here and I can challenge anybody on it."

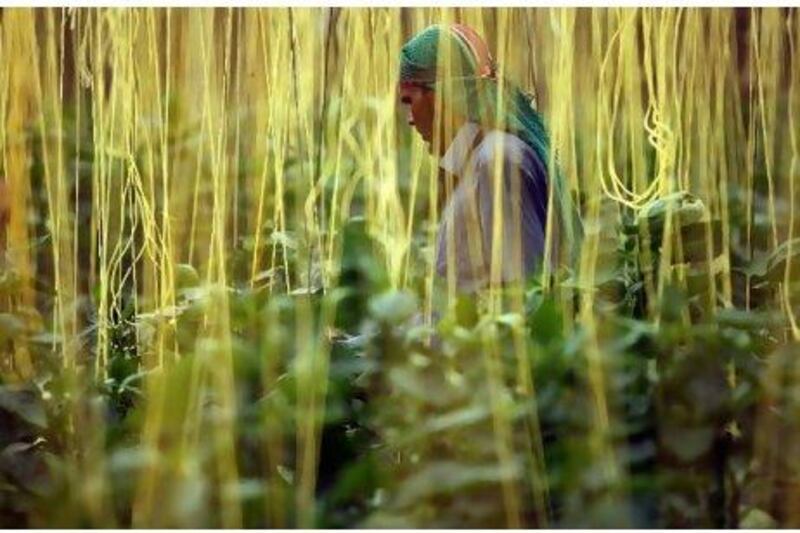

Others are equally gloomy. Osha owns a 4,000-square-metre farm in Liwa, where she grows courgettes, tomatoes, okra and cabbage. For the past two years, she has suffered severe financial losses.

"Farming has become unprofitable," she said. "The municipality used to pay me Dh25,000 a month for my produce but now it's not the same and I have no more money."

Her maintenance and labour costs have increased significantly, pushing her into debt.

Agricultural experts agree. Dr Ahmed Moustafa, the regional co-ordinator at the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas in Dubai, said agriculture here faced a "huge" struggle.

"Water, land and climate is everything in agriculture, and there is a lack of adequate technologies [to deal with that]," he said. "It all depends on the technology used on the farm and the management."

Smaller farms sometimes do not have enough money to invest in expensive machinery and without government subsidies, farmers are strapped for cash. The scarcity of natural resources also handicaps food production.

"The groundwater levels are low and the water is too saline," said Hool Abdelaziz Atallah, an agricultural engineer at Bin Hamoodah Agricultural Services in Al Ain. "There are so many factors that come into play, including no protection from the government on prices. There is no more profit in agriculture."

He believes local producers should move from growing crops to raising livestock for eggs, meat and poultry - areas in which the government regulates prices.

"As opposed to [crop] agriculture, you don't need a lot of water for these items and you can buy feed from Brazil or Asia," said Mr Atallah. "They should also look for anything that needs less water, like the production of mushrooms."

Officials insist on promoting the growing of crops and assure producers that the practice is feasible in a country where the arable land is 0.77 per cent of the total area.

"If [producers] are losing money, I don't think it's because of the environment," said Mohamed Jalal Al Reyaysa, the Abu Dhabi Food Control Authority's communications director. "It's because they are mismanaging their farms."

He said farmers should adopt new technologies and the right management methods to make a profit. Liwa, for instance, experienced many success stories with farms generating high quality produce sold on the local market.

"No one thought there would be any agriculture in the UAE but there is now and we have plans that can fit our environment by using less water and different kinds of soil," said Mr Reyaysa. "There are always ways."

Some farmers have already come round to the view that technology is the way forward. Salata runs a 16,000-square-metre farm in Ras Al Khaimah, growing 1,200 tonnes of lettuce, tomatoes, peppers, sweetcorn and herbs annually.

"We are going to invest Dh44 million in greenhouses and build our own power plant in 2013," said Thomas Schwarz, Salata's managing director. "This usually applies to bigger companies, not small farms."

This allows Salata to grow year-round, unlike most small farmers. That, said Mr Schwarz, is the difference between profit and loss.

"If you are [only] producing when everybody is, from December to April, it's very difficult," he said. "But if you are able to produce against the season, it's profitable."

But for Mr Khoory, the only way forward he sees is to all but get out of food cultivation, concentrating instead on his flower business, which requires less labour.

"I need something that I can continuously produce all year round to maintain a cash flow," he said. "Flowers are difficult to grow, but there is definitely more profit in it than the vegetable business."