Hamdy sits on a chair outside the crude shed where he lives on Ajban Farms in Abu Dhabi, directing a pair of workers who are harvesting grass feed for camels.

"When there's water, then the plants go strong," Hamdy says, his brow glistening with sweat in the early-morning heat. "At the moment the plants are weak and the palm trees are thirsty." Ajban Farms is thirsty. It is the UAE's largest single farming plot, a 29 square km grid of green in the desert consuming millions of gallons of desalinated water every year. "Open-air farming of grasses or cereals with desalinated water is very inefficient and not sustainable," says Eckart Woertz, an economist at the Gulf Research Centre in Dubai.

"It would be better to give [the farmers] the money directly and try to find more sustainable jobs for them in other sectors." The desert farms are in some ways a microcosm of the struggle with water in Abu Dhabi and the region. Although countries in the region have the world's smallest natural reserves of fresh water, governments in the Gulf have long promoted agriculture to reduce reliance on imported food and to diversify economies away from oil.

But the rapid rise in acreage under cultivation in the past decade has threatened groundwater supplies and created a huge costfor the Abu Dhabi Government, which has boosted investment in desalination plants and water infrastructure. The Environment Agency-Abu Dhabi (EAD) acknowledged the problem last year in its master plan for water, in which it warned groundwater supplies could be exhausted in between 20 and 40 years, and called for cuts in subsidies.

Meanwhile, projects such as Ajban have been supplanted by energy and industrial investments such as Masdar City, the carbon-neutral city under construction just a few kilometres from Ajban. Masdar City is aiming to achieve one of the lowest per-capita water consumption rates in the world. The thousands of small farms at Ajban and other sites nearby on the Abu Dhabi-Dubai road were never meant to be highly profitable.

They were built in the late 1990s and early years of this decade and distributed free to Emiratis to provide jobs, control the harsh desert landscape and give food security to a country that was heavily dependent on imports. Unlike inland farms that draw brackish water from underground and purify it on site, the farms of Ajban rely almost completely on fresh water pumped in at great cost from the emirate's power stations.

Ajban's principal crop, Rhodes grass, is grown year-round and sold to the municipality as forage for camels and other livestock. When all of the hidden costs of production are added up, it is probably some of the most expensive grass in the world, Mr Woertz says. The subsidies for Rhodes grass alone totalled Dh800 million (US$217.8m) in 2006, the latest year for which data were available, the EAD said last year.

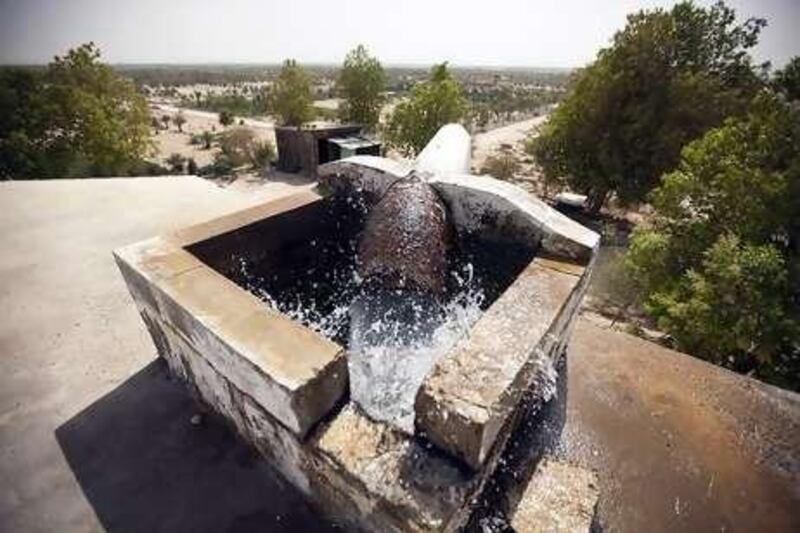

But the costs are something Ajban's farmers rarely contemplate. Water comes free of charge from the municipality, gushing down to the farms from seven 10-million-gallon water tanks perched on earthen platforms. When the farmers harvest their crops, they also have a ready buyer: the municipality. Waleed Eissa, a farm owner at Ajban, has worked his plot that measures 200 metres by 200 metres since 2006, when he moved from a different farm in Khalifa City.

"This area used to be desert, a very harsh environment," Mr Eissa says, sitting on a couch in his cosy, oblong farmhouse. "Nothing would be able to reach here. I came to this exact spot 10 years ago and in those days we used to hunt for game. It's unbelievable how it has changed." Mr Eissa says he tries to save water where he can as the municipality's supply has been intermittent recently because of maintenance, but few of the farmers appear interested in the environmental toll of Ajban and farming centres like it.

"Farming is very important. Now, when people go to buy fruits for example, you go to the souq and the product is from Lebanon, Syria. Why?" Mr Eissa says. "They have water, we have water, it's all the same." In the summer heat, the small plot of land consumes more than 11,000 litres of water a day, according to his rough estimates. For the three hottest months of the year, Mr Eissa's water costs the Government Dh7,878, using the EAD's estimate that it costs the Government an average of $1.75 to produce each cubic metre of water.

This is a drop in the ocean when you consider there are hundreds of such plots in the vicinity. The Government's challenge is to understand exactly how much precious desalinated water is sent to commercial farms, officials say. The EAD's master plan noted that officially 11 per cent of potable water went to farms, but "in practice this is likely to be far higher". A water study commissioned by the Executive Affairs Authority in 2008 could not account for the use of two thirds of the water produced at the emirate's desalination plants, although government officials stress in the years since, water suppliers have had better understanding of irrigation consumption.

Within Ajban and on plots nearby, some farmers are making visible efforts to use less water by growing food in greenhouses, using drip irrigation and covering their cisterns to limit evaporation. Changing the soil's composition by adding clay and mulch would slow water drainage, and putting irrigation systems underground could significantly reduce water use, says Adam Bradley, a manager and irrigation expert at ValleyCrest, an international landscaping company with a regional office in Al Ain.

But subsidies and the small-scale nature of each farm give owners little reason to invest, Mr Bradley says. "If the farm owners are not paying for the water, I cannot see any real incentive for them to worry about wastage or consumption," he says. "If agricultural irrigation water is charged for here in the UAE, I would expect all local operators would quickly reassess their water consumption. Anything grows in sand - you just need to add lots of water."

For now, at least, Ajban and other agricultural projects do not appear to be on their way out. And despite the hard work in the summer heat, and recent maintenance that has slowed the flow of water to a trickle, Mr Eissa says he is there to stay and even wants to expand his output. "I started to plant oranges and pomegranate, and nectarine, and lemon, which is growing slowly," he said. "I want to plant with larger capacity, but I am afraid the water will not be enough."

* additional reporting by Hadeel al Sayegh

cstanton@thenational.ae

afitch@thenational.ae