WADI AL HAYL // It's a typical wadi to the untrained eye, consisting of brown rock and dry, dusty river beds. To Dr Michele Ziolkowski, however, it is an open-air art gallery that tells the story of those who lived there thousands of years ago.

Dr Ziolkowski is a neophyte by comparison. She came to the UAE in 1993 as an undergraduate student from the University of Sydney and first worked at the Fujairah site on a metallurgy survey. A group of petroglyphs - pictures or inscriptions carved in rock - caught her eye while on the job. "Once you know what you're looking for, you can find them everywhere," she said. "I found about 65. I had my honours thesis [in archaeology]."

She is in a race against time to find and document the rock art before it is lost to quarrying, mining and construction work. She is doing pretty well. The number of known rock-art sites in the Emirates has more than tripled from 16 in 1998 to about 50 today, containing more than 500 petroglyphs. There are more than 100 at Wadi al Hayl and there may be thousands throughout the Emirates. Local experts agree that the symbolic sites should be maintained. Salah Hassan, the resident archaeologist with the Fujairah Tourism and Antiquities Authority, welcomed the idea of preserving Wadi al Hayl and its relics.

"There is big work required on these petroglyphs," he said. "We started in the 1990s with Michele and recorded a lot of petroglyphs, but now we need to arrange for a bigger project, for a disciplined work on this." Parallels with other artefacts provide an idea of what a symbol consists of, who made it and when. It is therefore vital that petroglyphs, where context is everything, stay in their original environment. That makes Dr Ziolkowski's race against time all the more compelling.

Some symbols have already been lost. Dr Ziolkowski recorded 119 petroglyphs in Wadi Daftah before many were destroyed by road construction. She also worked against time to finish documenting a group of glyphs before the blasting of a chromite mine. "You need to have the area properly managed," she said. "Make it a national park. There are so many people who study archaeology and history and they could run guided tours."

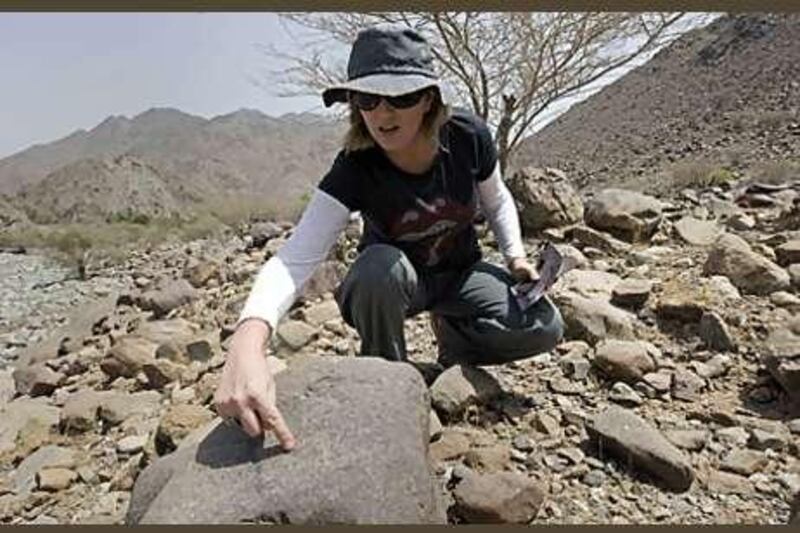

The Wadi al Hayl petroglyphs are hidden on a road that will probably be washed away next year. Dr Ziolkowski revs her Toyota Land Cruiser over washed-out boulders, oblivious to the cliff crumbling below her, to reach them. "Don't be disappointed," she said, parking beside some sun-scorched stones. "The first few don't look like much." She pours water over a few scratches on an otherwise unremarkable rock. A triangle and some lines appear. They make up the figure of a horse and rider, a glyph found from Yemen to Jordan and believed to date from the third century BC.

Dr Ziolkowski then points at a rock beside the first containing a foot-shaped petroglyph, possibly used as a marker. A few steps away, there is another glyph depicting a pair of snakes, often found in relation to religious sites. Both sets of symbols are believed to date from the Iron Age, which ran from 1300BC to 300BC. Dr Ziolkowski believes most of the Wadi al Hayl rock art was made by percussion, hitting the rocks with another piece of stone, probably quartz, a hard rock in abundant supply. That system probably includes the next set of symbols she points out.

"Check these out - a demon body shape, symbolically shackled," she calls from a sandy slope. She then holds up an Omani pendant. One side has Quranic inscriptions, the other a small figurine of a body. There are short lines etched across its legs. While it is almost identical to the nearby figure carved in the rock, the difference between them in age could be 3,000 years. It is Lamashtu, the legendary demoness of ill health. Depictions of her date from late in the first millennium BC. Similar drawings were found on amulets from Mesopotamia and are still worn today as talismans against spiteful spirits. The figure's curved sword ties it to the Iron Age. "The legs have been symbolically shackled to slow down and stop the genie," says Dr Ziolkowski. "In terms of symbolism you have a pre-Islamic tradition that has become part of the Islamic tradition."

"Sometimes I wonder if they were used as markers or made by a bored goat herder who decided to chip-away on a rock surface," says Dr Michele Ziolkowski. Regardless, the original meanings of many have been lost in time. One theory is that they mark direction. Another theory is that they were tribal markers, or wusum, which are usually geometric patterns. Some may have been used for hunters' magic. Hunters may have hit the stone drawings to bring them good luck before a hunt. One petroglyph in Wadi Saham, "looked like it has been deliberately hit all over". "They were like little missiles, just little dots pecked out all over the rock, so it almost looked like it was a hunting scene," says Dr Ziolkowski. "There is this idea of hunting magic, sort of a mystical form of hunting to help you prepare and have a successful hunt." Near the village of Roweida, the original purpose of one petroglyph was long forgotten, but it is used as an important marker for the trek from Dibba to Ras al Khaimah. "The villagers know it," says Dr Ziolkowski. "They stepped in and they actually protected it. That one was interesting because even though they didn't make it, they use it." Though only stone, the petroglyph is still alive with meaning. @Email:azacharias@thenational.ae