Few Arabian oryx remained in the wild when Sheikh Zayed issued the order to round up some of the animals and bring them to Sir Bani Yas. Today the sanctuary is a thriving facility that bears testament to the founding President's conservation goals, James Langton writes

They were the last of their kind. A tiny band, probably less than a dozen strong, rescued from oblivion by an audacious plan that took them from the harsh interior of the Rub Al Khali, or Empty Quarter, to a distant island in the Arabian Gulf.

It is 40 years since the island of Sir Bani Yas became the best hope for the survival of the Arabian oryx. At the time, many feared the species could not be saved.

Video: Sir Bani Yas, the desert miracle

This old film clip from Abu Dhabi Television captures Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan speaking on Sir Bani Yas island while the island was still in the early stages of development.

Man, their only predator, had reduced their numbers to a handful.

Salvation came at the hands of Sheikh Zayed, the founding President. In the summer of 1971, the Ruler of Abu Dhabi was wrestling with the final issues that would lead to the creation of the UAE that December.

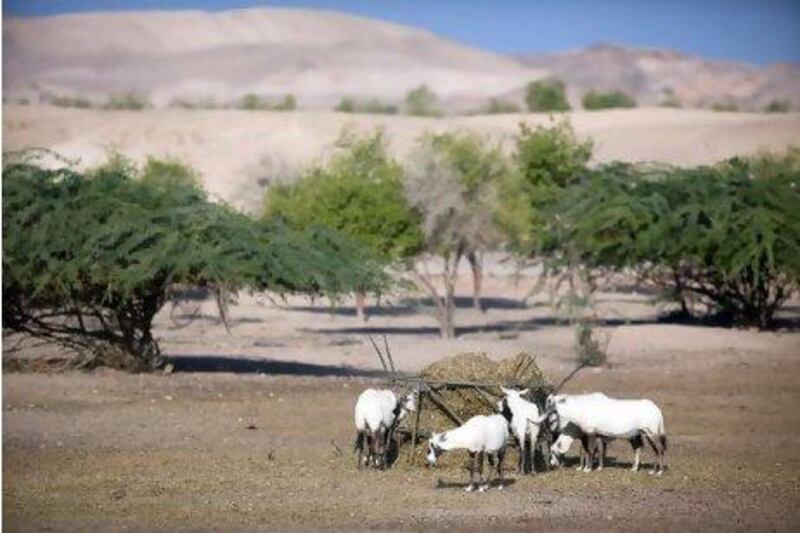

Conservation was very much on Sheikh Zayed's mind, though, and with it the urgent plight of the oryx, a magnificent antelope with a pure white coat and horns up to 75cm long.

Orders were given for a last round-up. Every wild oryx that could be located in the UAE was taken into captivity. A few were sent to the zoo at Al Ain. The rest, perhaps no more than eight, were taken to Sir Bani Yas, the country's largest natural island, 9 kilometres off the coast of Jebel Dhanna.

The rescue was carried out in the nick of time. The following year the Arabian oryx, once native across the entire Arabian Peninsula and much of the Middle East, was officially declared extinct in the wild.

But this is a conservation story with a happy ending. In four decades, those few surviving animals have grown into a herd that by next year should number 500.

Conservation measures have ensured the oryx has not just survived but thrived. The species is no longer considered endangered and Sir Bani Yas is now a key component in a sophisticated project to reintroduce the animal back into the wild.

Before its reincarnation as a wildlife sanctuary, the island had an ancient history. The very name ties it to the Bani Yas tribe and the Al Nahyan family, rulers of Abu Dhabi.

There are a number of Bronze Age sites and the remains of 7th-century Nestorian monastery, the oldest pre-Christian site in the UAE, discovered in 1992.

In the 1970s, Sheikh Zayed embarked on an ambitious plan to plant tens of thousands of trees and plants across what had been a bleak vista of rock and scrub.

Desalinated water was sent through an undersea pipeline to a drip irrigation system. When the first oryx arrived, the island was already developing a cover of lush vegetation.

Historic footage survives of Sheikh Zayed visiting the island in the 1980s and talking about his ambitions as a conservationist. Sitting cross-legged on a low hill overlooking a small group of oryx, the President shows an encyclopaedic knowledge of the island and its animal population.

The Arabian oryx, he explains, is "called Al maha in Arabic. Tribes refer to it as widhehi". The President is able to list every species of animal on the island.

"They are cared for constantly," he says. "The veterinary doctors in Al Ain Zoo monitor them too. Now that their numbers are growing, we will bring in vets to live on the island.

"They need professionals to monitor their feeding habits and provide them with the best nutrition suitable for them. They can treat the animals and administer the proper drugs for them when needed."

Marius Prinsloo is the senior manager for conservation and agricultural services with the Tourism Development & Investment Company, which now runs the island as part of Abu Dhabi's Desert Islands project.

Mr Prinsloo has worked on the island since 1991 and recalls visits by Sheikh Zayed. The trees, he says, were personally chosen by the late President.

"Sheikh Zayed used to pay regular visits to the island, around twice a month, for following up on the progress of work on the island related to agriculture, trees planting and wildlife conservation," he says.

"He was keen on the miswak tree, which provides a perfect habitat for birds' nests and is a source of food for various types of animals.

"Sheikh Zayed also favoured the ghaf tree, due to its ability to act as a refuge for animals looking for shelter from the sun in the summer and rain in the winter, as well as supervising the planting of mangroves, which protect the soil from erosion and are a source of food for birds.

"Sheikh Zayed ensured that there were also vast open areas on the island for free-roaming wildlife."

Seven years after his death, Sir Bani Yas has become part of Sheikh Zayed's legacy. In June 2006, 87 female Arabian oryx were released into a 9,000 square kilometre sanctuary at Umm Al Zamool, with the intention of creating a sustainable population in a natural environment. Since then similar numbers of oryx, including eight pregnant females, have been released into the sanctuary, most recently in March.

The conservation programme on the island and at Al Ain is also part of a wider international effort to save the oryx, adding animals to a wider genetic pool for breeding.

In June this year, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) re-categorised the Arabian oryx on its red list of threatened species. The oryx was removed from the extinct list and upgraded to vulnerable, the first time this has happened.

The IUCN now estimates there are about 1,000 animals back in their natural habitat, and perhaps as many as 7,000 in captivity.

Conservation measures on the island have also brought another endangered species back from the brink. The scimitar oryx, named after their distinctively curved horns, was hunted to extinction in the wild but has yet to be reintroduced.

The island's herd of scimitar oryx may be the largest in the world and will play a key role if plans go ahead to return it to the wild.

Other animals have bred almost too successfully. Nearly half the island's population of 15,000 animals consists of diminutive sand gazelles. In an attempt to bring a more natural balance to the island's population, a small group of cheetahs were introduced in 2009.

Raised in captivity, the cheetahs were encouraged by conservation workers to rediscover their hunting skills, and three - a female and two males - have been released into the vast fenced enclosure that covers the centre of Sir Bani Yas.

Each of the animals makes several kills a week. To clear up the carcasses, several striped hyena have been added to the collection, and most recently a jackal.

The island is also home to a large and growing population of rock hyrax, a small rodent-like creature that resembles a guinea pig but is actually related to the elephant. To control their numbers, a breeding pair of caracal cats, or lynx, have been brought to the island.

Forty years on, Sir Bani Yas is a very different place to the island first visited by Sheikh Zayed. There is a greater emphasis on preserving flora and fauna indigenous to the region and Sir Bani Yas is now a major tourist attraction, with the Ruler's former guest lodge converted to a five-star resort from where tourists can take guided safaris among the animals.

While there are plans to increase the number of visitors, conservation still remains at the heart of life on the Sir Bani Yas.

Aimee Cokayne, a research and conservation officer on the island, says there is something in the air that seems to persuade even the most reluctant animals to breed successfully after their short sea journey.

"Some people call this place the Arabian Ark," Ms Cokayne says. "We really owe it all to the foresight of Sheikh Zayed.

"We might not have the Arabian oryx now without him."

[ jlangton@thenational.ae ]