ABU DHABI // The Emirati public sector employment market is reaching "saturation point" and the Government should focus on educational reform and the subsidisation of private sector wages rather than Emiratisation quotas, according to a new policy study. The state can no longer act as an employer of first and last resort and public sector jobs should not be part of the "social contract" by which the Government distributes oil wealth to its nationals, according to the radical report to be published later this year.

Instead, the Government should concentrate on diversifying the economy, greater career exploration in school and college, subsidising the salaries of Emiratis in the private sector and increased support of state-owned private companies. The study was compiled by researchers from United Arab Emirates University (UAEU) and will be published during the summer in the Middle East Policy journal. The authors present a range of solutions to boost employment and communicate the message that over-reliance on the Government for employment is not feasible, drawing on wide-ranging employment research.

Concern has been rising over Emirati unemployment, which has reached 14 per cent in the capital. In January, the director general of the Abu Dhabi Education Council called the figure "alarming", saying it demanded urgent attention. Emiratis make up just four per cent of the private sector workforce, compared with 52 per cent of the public sector. "There is a growing realisation within the region that public sector bureaucracies have reached the saturation point. They can no longer act as an employer for first and last resort," the study says.

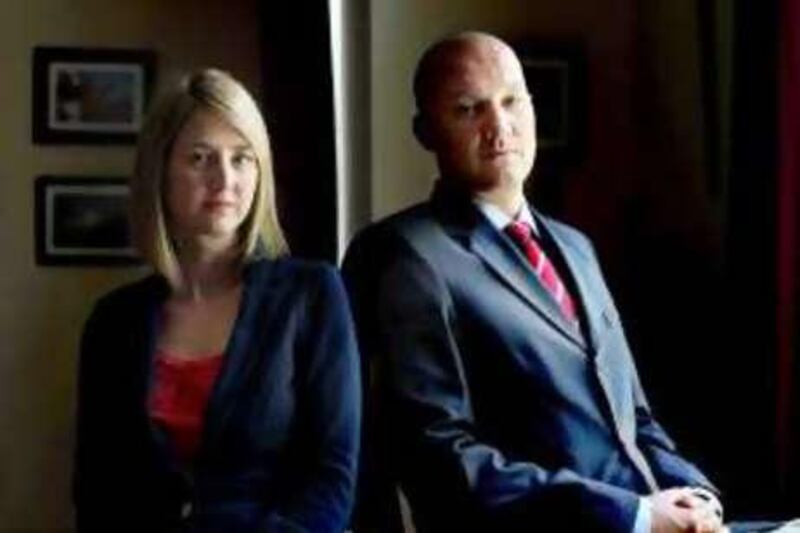

Ingo Forstenlechner, assistant professor of human resources management at UAEU, and one of the paper's authors said: "The dream of most of my students is to work in the municipality. That's not going to help the country and it's not going to be possible." His co-author, Dr Emilie Rutledge, an expert on Gulf fiscal policy, is an assistant professor of business and economics at the same college. Feddah Lootah, the acting director general of Tanmia, the UAE's employment agency, said the deep divide between the public and private sectors was to blame for Emiratis' preference for government jobs.

Experts often argue that the higher wages, shorter working hours and greater job security of the public sector act as incentives that drive locals away from private companies. "Not only this, but they continue to encourage the private sector to import and recruit cheap foreign labour under the umbrella of competitiveness," said Ms Lootah. Under-15s make up roughly 39 per cent of the Emirati population in the capital, and those between 20 and 40 constitute 40 per cent. Emiratisation experts argue that the public sector cannot absorb such large numbers.

This new approach is necessary because many long-standing employment policies have not reversed the absence of nationals in private companies, the paper says. Employers still lack confidence in the country's education system. A survey by the Mohammed bin Rashid Foundation found that just half of Arab executives felt that nationals were competent enough to work in their industries. This was because the education system rarely adhered to the needs of private sector employers in the Gulf, said Ms Lootah, which "was at the core of these countries' dilemma of importing expatriate labour to bridge the vacuum of qualified human resources".

This gap was still contributing to the unemployment of new national graduates, she added. Almost double the number of students in Grade 12 in the UAE choose the humanities track instead of sciences, according to the Ministry of Education, contributing to this gap in expertise. Many attempts at diversification have met with limited success. Manufacturing is not viable because of the small size of Gulf markets, and job categories like hairdressing and waitressing are deemed inappropriate for the local population, the paper says.

Quota systems, which require private companies in some sectors to hire a set percentage of Emiratis, call into question the "region's business-friendly persona". Affinity towards the government sector had contributed to unemployment because many nationals preferred to stay out of work for years rather than work at a private company, said Dr Forstenlechner. One solution, he said, was to strengthen state-owned private companies. Another was to subsidise private sector employees from the UAE, "topping up their private sector salary" or giving them government pensions.

He said the UAE's significant investment in educational reform and new university campuses were good first steps. The country's nuclear programme has won praise for including a development plan that ensures the deep involvement of Emiratis. Shaikha Eissa, a public sector employee at the Ministry of Social Affairs, who used to work for a private company, felt that concern that the public sector was "saturated" was overblown, but said she would not mind working for a private company again.

"Both types of jobs are enjoyable, I don't know why people make a big deal out of it," she said. "As Emiratis, we aren't scared of the private sector. There is no constant worry that the company might fail, because our Government stands by us even if we are in the private sector." She acknowledged that working in a government job could often be comfortable, but "work in the private sector is enjoyable and has creativity, and you can play a big role in the company".

Ms Eissa said she preferred working at the private company as it had better long-term incentives and individuals were more likely to shine. While the public sector constantly needed new blood to replace its retirees, "if I had the chance, I would work in the private sector because it has a future." kshaheen@thenational.ae