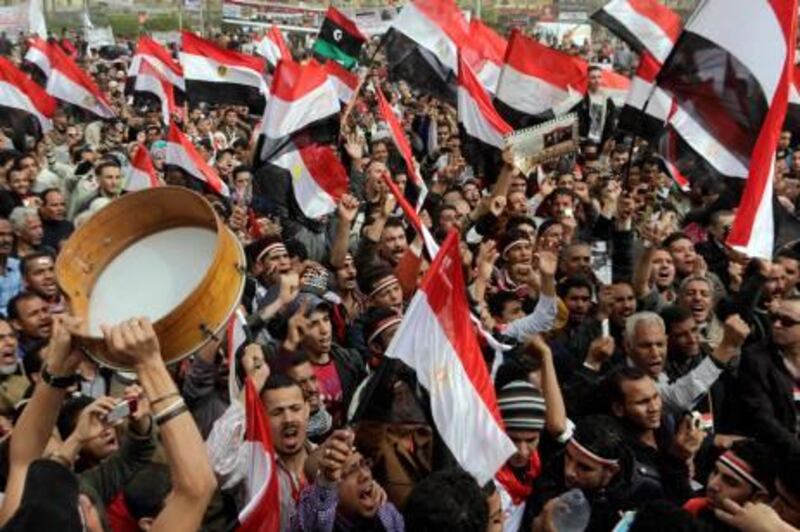

CAIRO // The tens of thousands of youth protesters who again took to Egypt's streets yesterday all shared a central concern: on paper, they have no more freedoms than at the start of their revolt a month ago.

Egypt officially remains under a state of emergency, as it has for nearly all of the past 44 years. That means that the country's new military rulers, just like the former president Hosni Mubarak, have unchecked powers to quash civil rights, shut down private business and detain suspected dissidents.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces has promised to end the state of emergency as part of its efforts to transform Egypt into a democracy, but indicated it needed six months to find a balance between the demands of protesters and the need to fight terrorism and drug trafficking. Most protesters, however, see no reason for the law's continuation and are demanding it end immediately.

The approach that military leaders ultimately take will serve as a measure of their commitment to democratic reform but will also be shaped by the threat of terrorism, experts say.

Protesters see the emergency law, in effect since Mr Mubarak became president in 1981 and for most of the country's history since 1967, as the root cause of the growth of an abusive police state in Egypt, said Gamal Eid, a civil rights lawyer and the executive director of the Cairo-based Arabic Network for Human Rights Information.

"There is no reason to continue, and this is the best time for the military to demonstrate it respects the people's opinion," he said. "Every day that the government runs under the emergency law, the people get angrier and angrier."

Along with Mr Mubarak's resignation, ending the state of emergency and its corresponding emergency law was the most important demand for protesters who first organised on January 25 to call for an end to abuses by security forces.

The emergency law, which was put in place by Mr Mubarak to give the government wide powers to disrupt terrorist activity after the assassination of the then president Anwar Sadat, created a sense of "impunity" among security forces, Mr Eid said.

Under the law, authorities can ban protests, shut down media and private shops, search homes without a warrant, and detain those "suspected of disrupting public order" without a warrant or court order. The emergency law, paired with a 2007 constitutional amendment called Article 179, gave government officials nearly unlimited powers to indefinitely detain terrorism suspects and refer them to state security courts or military courts where rules on evidence are less strict and a conviction is easier to obtain.

"There is no decision by a court, it was always a decision by the interior minister and led to a regime of systemised torture," said Mr Eid, who estimates that the emergency law's provisions allowed tens of thousands of detentions in the past 20 years.

In a secret cable last year to Washington published this month by WikiLeaks, the US Embassy in Cairo concluded that the Egyptian government abused its powers under the state of emergency.

"While often used to target violent Islamic extremist groups, the [government of Egypt] has also used the Emergency Law to target political activity by the Muslim Brotherhood, writers, activists and others," the cable said. "The Interior Ministry uses the [State Security Investigations Sector] to monitor and sometimes infiltrate the political opposition and civil society, and to suppress political opposition through arrests, harassment and intimidation."

But the same cable also noted that the law has proved to be a valuable tool in Egypt's ongoing fight against militants, echoing the arguments of Egyptian security officials. Egypt has experienced a number of terrorist attacks in the last decade, including the bombing of a Coptic church in Alexandria last month that killed 23.

When Egypt's parliament extended the law for two years in May, Ahmed Nazzif, the prime minister, claimed the law "has spared Egypt many terrorist dangers and nipped in the bud several other terrorist crimes".

Protesters do not know what to make of such claims, since the government has not volunteered many examples where serious plots were disrupted. Critics point to last month's church bombing and other incidents to argue that the emergency law is not making Egypt safer.

The emergency law, "did tend to give the government an extra ability to round up suspects who might have been associated with al Qa'eda and Hizbollah", said Theodore Karasik, the director of research and development at the Institute for Near East and Gulf Military Analysis.

But even without the emergency law, a new government will likely try to invoke many of the same powers, he said, though through different, and perhaps more circumscribed, legal channels.

The military's willingness to give up the broad powers under the emergency law will depend heavily on the security situation, he added.

"If a terrorist attack occurs, I think it's a game-changer and will affect the course of the country in the short term, and how it moves to a more democratic Egypt," he said.