CAIRO // It will be a brief but historic encounter, symbolising an end to three decades of animosity between two of the region's oldest, proudest and most powerful nations.

On Thursday, when he attends a summit of the Non-Aligned Movement in Tehran, Mohammed Morsi will be the first Egyptian president to set foot on Iranian soil since the 1979 Islamic revolution.

He will top Iran's list of prized guests: one jubilant senior parliamentarian said the visit represents a "failure for the United States".

Mr Morsi will spend only four hours in Iran - long enough to signal a new foreign policy direction but brief enough to reassure Egypt's benefactors in Washington and the Arabian Gulf that he is not shunting them aside.

Egypt's new Islamist president is both pragmatic and cautious. His spokesman, Yasser Ali, made it clear on Sunday that Egypt had no plans in Iran other than to attend the summit. But he did lay out how Mr Morsi was aiming to reconfigure Egypt's international posture so that it could regain its prominence in the region after years of stagnation under Mr Morsi's predecessor, Hosni Mubarak.

Egypt will aim "to be more agile and more active," Mr Ali said. "Our philosophy of international relationships is based on the concept that we are not in competition or rivalry with any country … we would like to have a balanced relationship with every country. We do not belong to any political axis."

For its part, Tehran is keen to establish relations of "friendship and brotherhood" with Cairo, Iran's foreign minister, Ali Akbar Salehi, said last week.

During his term in office, Mubarak sided with Saudi Arabia and other states in trying to isolate Iran. A secret US diplomatic cable dated April 28, 2009 and later obtained by WikiLeaks quotes Mubarak as saying Iran was "the greatest threat to the Middle East".

While keen to maintain long-time alliances, Mr Morsi is determined to redress what he sees as an excessive tilt towards the West and Arabian Gulf countries and restore Egypt's role as a key regional player.

"He wants to reclaim the position Egypt once had as a pivotal Arab country, an ambition that has popular support in Egypt," said Gerald Butt, author of several books on the Middle East.

It is not known whether that means an imminent resumption of full diplomatic relations with Tehran, which would dismay Washington.

And few analysts believe a diplomatic rapprochement would ever evolve into a strategic alliance. Iran and Egypt are natural competitors with different strategic interests, they say.

Mr Butt described the Egyptian president as a pragmatist who "won't cosy up to Iran to the extent that he'll be cold-shouldered by the Saudis or Americans".

Omar Ashour, director of Middle East Studies at Exeter University in England, agreed.

"Egypt doesn't want the cold relationship with Iran that it had under Mubarak," he said, "but it also wants to stay in the alliance with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf because of political, economic and geo-strategic reasons."

Egypt relies heavily on US$1.3 billion in US military aid and is awaiting billions of dollars in grants from Arabian Gulf nations.

Mr Morsi's first trip abroad as president was to Riyadh - a signal that he has no intention of alienating the kingdom. Next month, equally significantly, he visits the US, another benefactor.

While Cairo is treading gingerly, Tehran seems like an over-eager suitor, desperate to reverse its increasing international isolation.

In June, Iran hailed Mr Morsi's election as an "Islamic awakening" only to have him threaten to sue an Iranian news agency after it quoted him as saying he was interested in restoring relations with Tehran.

Tehran's eagerness to ingratiate itself with Mr Morsi is a far cry from its hostility more than three decades ago.

The revolutionary government in Tehran severed formal ties with Cairo in 1979 in protest at its peace treaty with Israel. It was also furious that Egypt had given asylum to Iran's ousted dictator, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who died of cancer in 1980 and was buried in a tomb at a Cairo mosque.

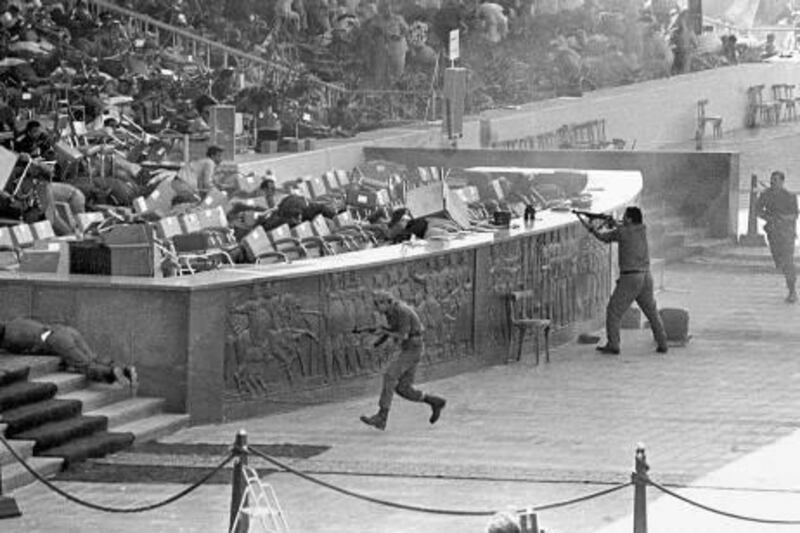

The young government's rancour towards Cairo is perhaps best symbolised by a leafy avenue in central Tehran named after Khaled Islambouli, the ringleader of the assassins who killed Anwar Sadat, the Egyptian president who made peace with Israel. Mubarak, Sadat's successor, was routinely derided by Tehran as an "American puppet" and a calcified "pharaoh".

Post-Mubarak Egypt has shown signs of not dwelling on this fraught past. Days after Mubarak was toppled, Cairo allowed two naval ships to transit the Suez Canal, the first to do so since Iran's Islamic revolution.

Since then, hundreds of extremists have been released from prison, including Mohammed Shawki Islambouli, the brother of Sadat's assassin. Mr Morsi himself has used his powers to help to free Islamist extremists imprisoned by the Mubarak regime.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces - the group of military generals who ran Egypt until Mr Morsi became president - ensured that Cairo would not rush to overhaul Egyptian-Iranian relations, going so far as to push from office the foreign minister, Nabil Elaraby, a leading advocate of normalising ties with Tehran. Mr Elaraby is now head of the Arab League.

Although Iran's support for the Syrian president Bashar Al Assad has made it difficult for Egypt and other Arab states to reach out to Tehran, Mr Morsi is likely to feel less constrained in seeking some accommodation after Saudi Arabia's King Abdullah gave Iran's president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a warm welcome at an emergency summit of Muslim leaders in Mecca last week.

At the same gathering, Mr Morsi proposed Iran should be part of a four-nation contact group to mediate an end to Syria's escalating civil war that also would include Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

"Iran can be part of the solution, not part of the problem, if it is incorporated in this committee," Mr Ali, the presidential spokesman, said.

[ mtheodoulou@thenational.ae ]

bhope@thenational.ae