During Britain's recent general election, I spent a day or two in what was the Midlands coalfield, just missing a whistle-stop visit by Gordon Brown, the soon-to-be-defeated prime minister, by 10 minutes. It was something of a trip down memory lane; the last time I had been in these industrial towns around Nottingham and Mansfield was a quarter of a century ago, when the heart of the place beat to a different drum of coal mining, textiles and manufacturing. Now, only one colliery remained, the textile industry had long ago shifted to East Asia, and manufacturing, in the shape of a remaining engineering plant, anticipated possible closure. Most people I met who had jobs were employed in the public sector. They were - almost without exception - nervous about the future.

As a result of a leaked assessment from the British Treasury, the new government's austerity budget will possibly lead to 1.3 million jobs being lost across the British economy over the next five years, with up to half of them disappearing from the public sector. So where will all of those people who used to be miners, textile workers and engineers, who became public sector workers, end up? The best guess is that many will be unemployed, and certainly the new university graduates and school leavers will have a particularly tough time of it. Right across Europe, there is a real risk of another "lost generation" of jobless youths.

There are historical reasons for the particular weakness of Britain's manufacturing and export base, and this time there is only a declining revenue base from North Sea oil to ease the pain. The Anglo-American, deregulated, free-market model was long on the primacy of the financial services industry and short on its regulation. But right across Europe and the Euro zone, the story is becoming depressingly familiar.

Centre-right governments such as that led by Angela Merkel, the chancellor of Germany, are pushing ahead with austerity packages. Centre-left governments, such as that of George Papandreou, the Greek prime minister, are being forced to follow suit - but for them, and for southern European countries such as Portugal and Spain, the medicine risks so damaging the patient that the only real cure could yet be an exit from the euro zone altogether, or nightmare of nightmares, a default on debts, many of these owed to German banks.

While many Germans point to the profligacy of some of their southern neighbours, and a notoriously lax attitude to collecting taxation, others now accuse Germany of damaging the euro zone house they built, and in the same way that they pulled the rug from under the Exchange Rate Mechanism. "Germany always has to rebuild what she has just built in the first place and then dismantled," a former pro-European Conservative MEP, John Stevens, told me yesterday. And had Germany not allowed irresponsible lending to southern Europe, would those countries be in quite the mess they are today?

Chancellor Merkel now faces her own political problems with a fractious coalition, and a public alarmed at the sheer audacity of her deficit reduction programme. Reading between the lines of what President Barack Obama had to say during last week's G20 summit in Toronto, the US is pretty worried by Germany's austerity programme as well, fearing that Europe's biggest economy will shrink and that demand for US exports will shrink with it.

Incidentally this is just what some of the British prime minister David Cameron's critics are already saying about his budget of public spending cuts. Cameron and his finance minister, George Osborne, presume that a private sector, export-led recovery will lead to economic growth over the longer term. But the question comes back to bite them: who exactly will be buying British exports? How is this recovery to come about when domestic and European demand will be so depressed?

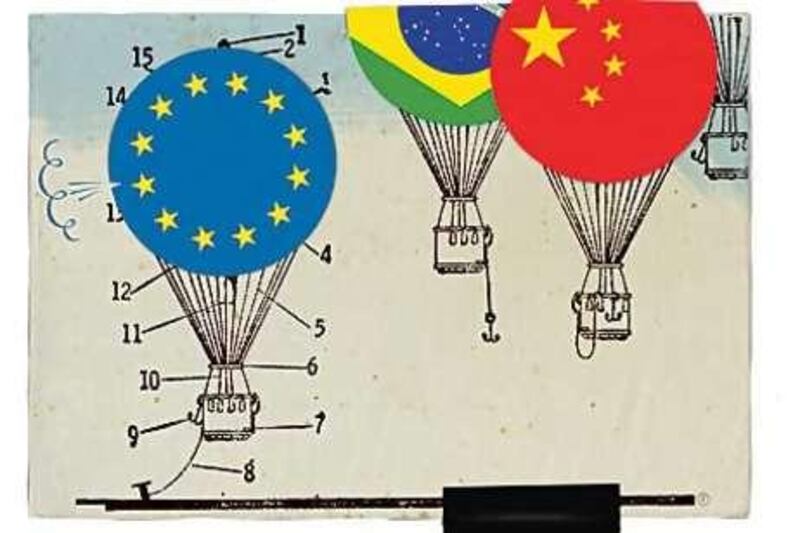

The shocking truth is that European economic growth has been level, pegging at around a measly two per cent over the past 15 years. This compares with Asian growth averaging eight per cent over the same period. Runaway economic growth in parts of China during the past decade - reaching an annual figure of 15 per cent in one province of the industrial north-east of the country I visited five years ago - so alarmed the Chinese government that it felt obliged to intervene to dampen down demand.

But there are more fundamental questions to be asked about this European growth figure, because some suspect that this relatively low average is based largely on European public spending, the "endogenous growth" once trailed with such enthusiasm by Alan Greenspan of the US Federal Reserve and adopted with such relish by Gordon Brown, and which in reality was fuelled by nothing more substantial than the dotcom and property boom.

Strip all of this out and it seems perfectly feasible that some European economies haven't really grown in years, and that little wealth is being generated from those older reliables of the real economy. Put like this, Europe begins to look just a little sclerotic, some parts more than others. It seems truly astonishing that only a few years ago, there were European politicians who genuinely seemed to believe that they had banished the economic cycle, and that there was "an end to boom and bust".

The United States may not have an awful lot to boast about either. Although the Obama administration has resisted the deficit hawks, it is not meeting the twin concerns of American voters - job creation and the economy. But for all intents and purposes America seems to be in a better place than Europe, even as the economic stimulus package begins to enter its wind-down phase. The real economic story of the next decade will continue to be the rise of China, the Middle East, India and Brazil, the latter with its burgeoning, consuming middle classes, whereas Europen countries, and in particular skewed economies such as those of Britain, risk slipping into a Japanese-style period of deflation.

Here is Richard Koo, an economist at the Nomura Institute in Tokyo, analysing Britain's massively deflationary, cost-cutting budget earlier last week: "The budget itself, I think, is rather poorly timed given our own experience in Japan. You never want to cut your budget deficit when the private sector is de-leveraging ? because we cut our budget prematurely in 1997, we entered into a very steep economic decline and it took us 10 years to pull ourselves out of that." Ouch.

That, then, is one scenario, but a more pessimistic view of the economic crystal ball has other economists and commentators fearing a second, double-dip recession, brought on by the contraction of the major European economies. While some Middle Eastern countries have not been immune to the global downturn, there are very basic and powerful raw material underpinnings to many of these economies, especially in the Gulf, which in any event have the wherewithal to ameliorate some of the worst effects of the downturn in construction and property by coming to one another's aid.

So while we can expect to see more Middle East shoppers and tourists taking advantage of a weakened euro and sterling in the coming period, as with so much else, Middle Eastern companies will increasingly be looking to the East, and likely be pullingback from the stagnant, declining West. For this the Europeans and the Americans have only themselves to blame. Mark Seddon is the former UN correspondent for Al Jazeera English TV and a UK political commentator