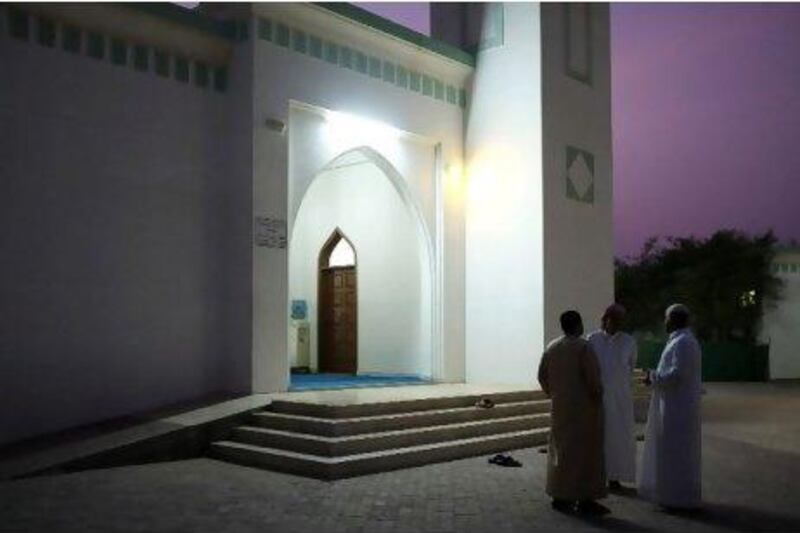

UMM AL QAIWAIN // The fluorescent lights of a Mohadhub village mosque serve as a beacon on winter nights for lost souls and lost campers.

The towering structure makes it easy to see why the English word for minaret shares a root with the Arabic word for lighthouse.

"This mosque is like a GPS," says Abdul Wahid Yousef, 31. "This tower is the identity of the mosque. From Sharjah, from Dubai, they come here camping and when they hear the call to prayer, they come to this mosque. Anybody who is lost here, he comes to the mosque - like a map."

Aqeel Ibn Ali Talib mosque's call to prayer can be heard for kilometres across the Umm Al Qaiwain desert. Its peeling sea green dome rises over the red sands as a landmark and lifesaver for dune explorers.

For most of the year the mosque serves the 80 families of Mohadhub, a village that consists of two mosques, one camel track and one grocery store. The village is abandoned after prayers, apart from a few dark shadows cast by lumbering cattle. If it is not happening at the mosque, it is not happening.

The Aqeel Ibn Abi Talib mosque was built at the centre of an empty desert flat by the government in 1997 and named for "a friend of our Prophet", said Mr Yousef.

Aqeel is one of the many historical figures the worshippers study at weekly Quran classes offered by the imam and his wife.

"They tell us stories about our friends of the Prophet and also about the wives of the Prophet - what they were doing," said Mr Yousef. "They talk about this because the wives did so many important things. We also have the place for the ladies in the mosque because here, in our Islam, the woman is very important. "

Sleepy teenagers answer the call to prayer more often since the Aqeel mosque opened. They can no longer use the excuse that the only mosque is a five-minute walk to "the other side" of the town's only street. "This side" of the street includes the mosque and two rows of houses with brightly painted doors. Apart from the occasional rogue camel, the hot and dusty square is devoid of life until the minutes before Maghrib prayer.

Doors open as dusk descends and men cross the square one by one, carrying enormous plates and pots of home-cooked favourites such as fareedh, a tomato-based meat and dumpling stew, and harees.

It is an old Ramadan tradition that has been replaced in the cities by large iftar tents and mass charity iftars. Here, where numbers are few, migrants and citizens break their fast together. "Here in Islam it's all one," said Mr Yousef. "Any person in Islam is my brother."

Abdulla Salem, 17, and his brother Saif, 13, pull up in a pick-up and unload a platter of fish.

The culinary masterpieces of wives and mothers are laid inside a hut next to the mosque and each man is poured a cup of Vimto. Workers from the surrounding desert sit next to men from the village. "These people are very good people, and love all guests. So we come here," said Gul Badshah Pirzad Gul, an electrician who has worked in the area for 35 years and has a wife and children in Pakistan.

It is not the meal he has come for but camaraderie, and he knows where to find it.