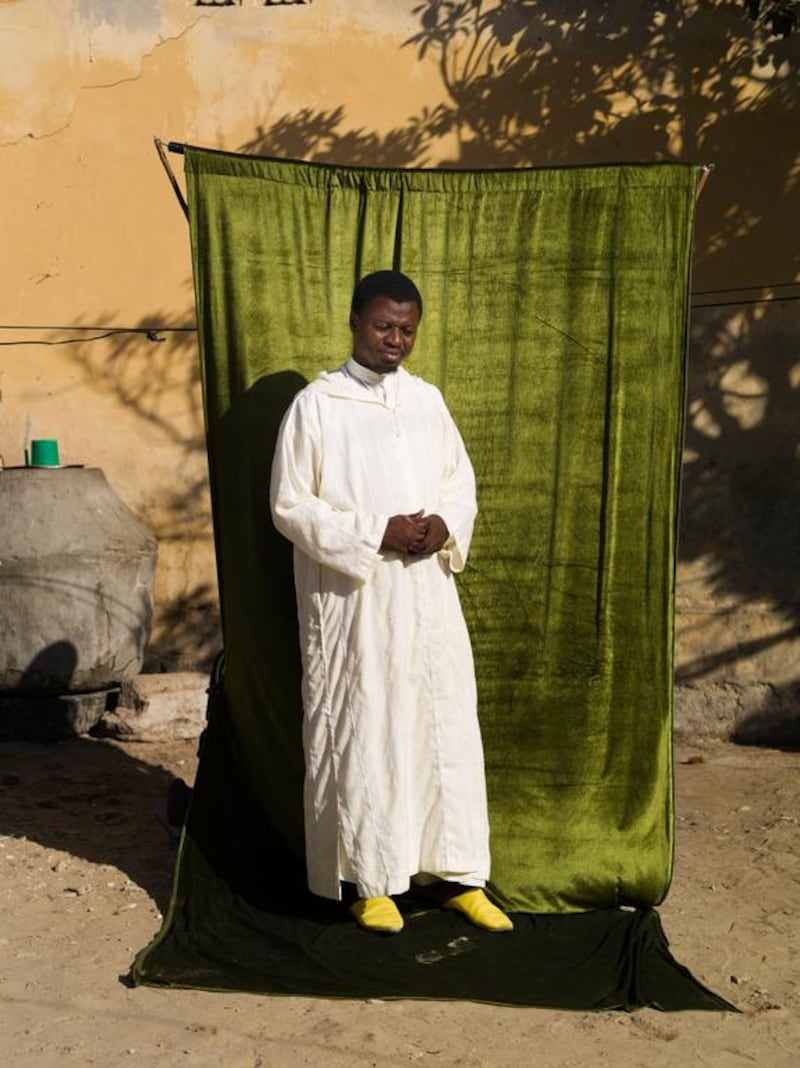

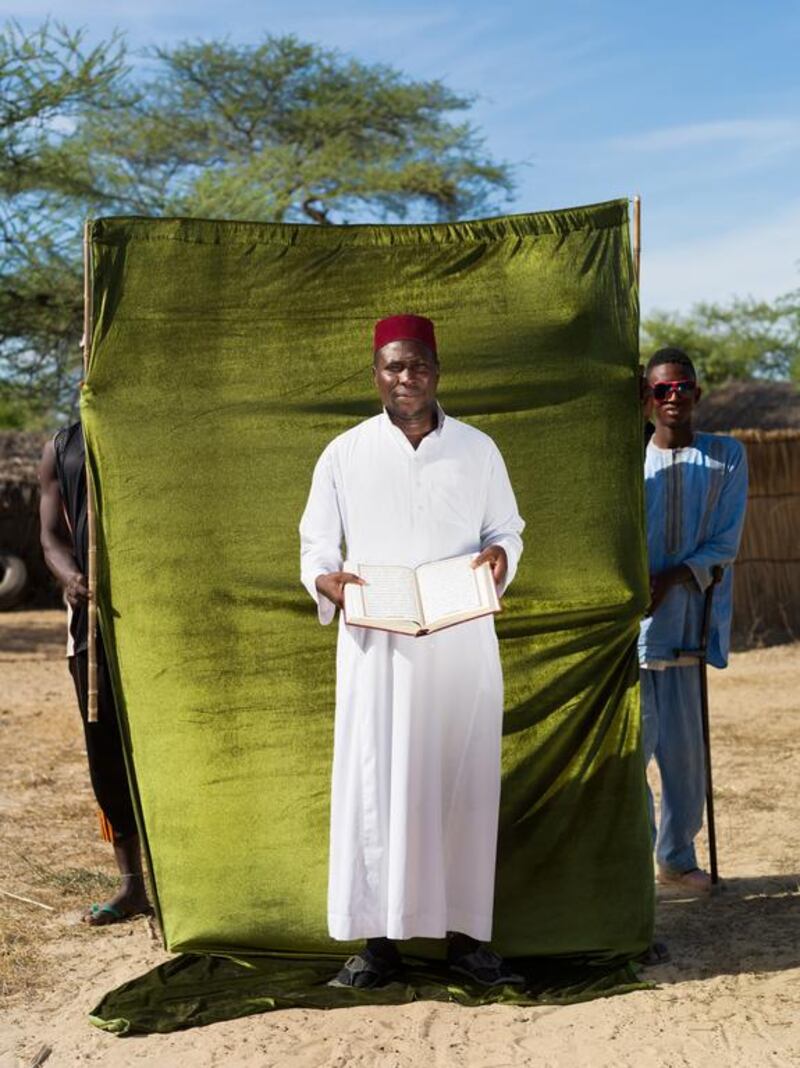

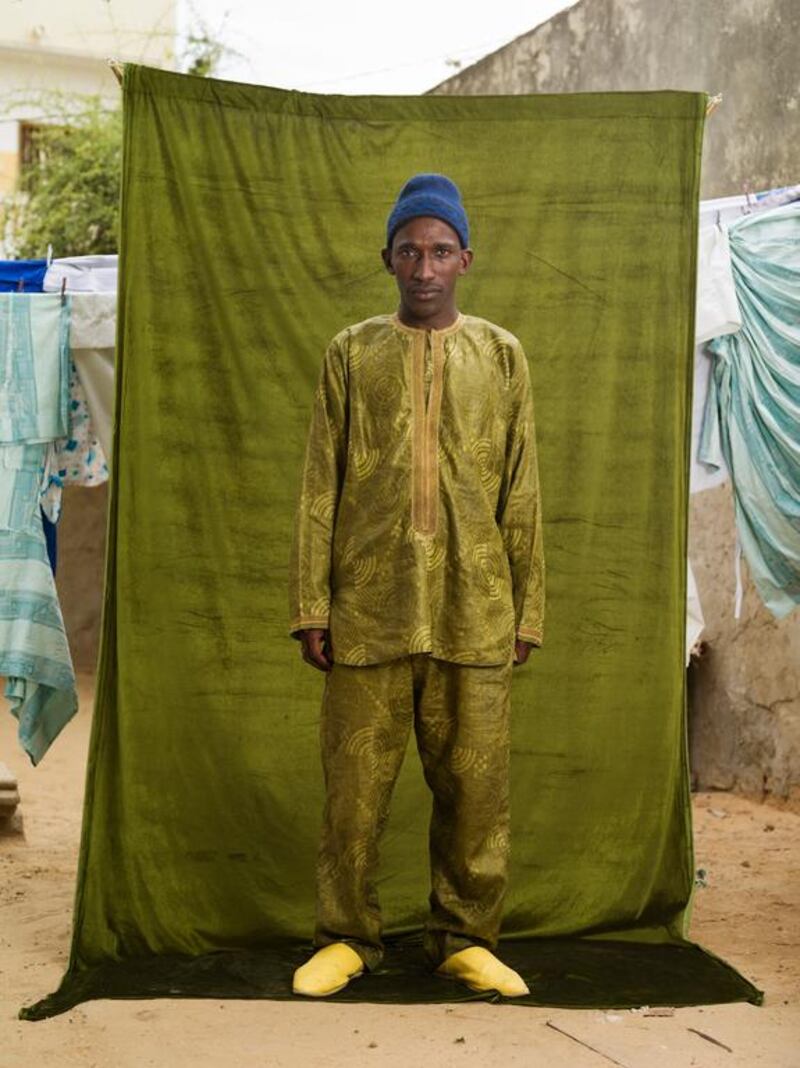

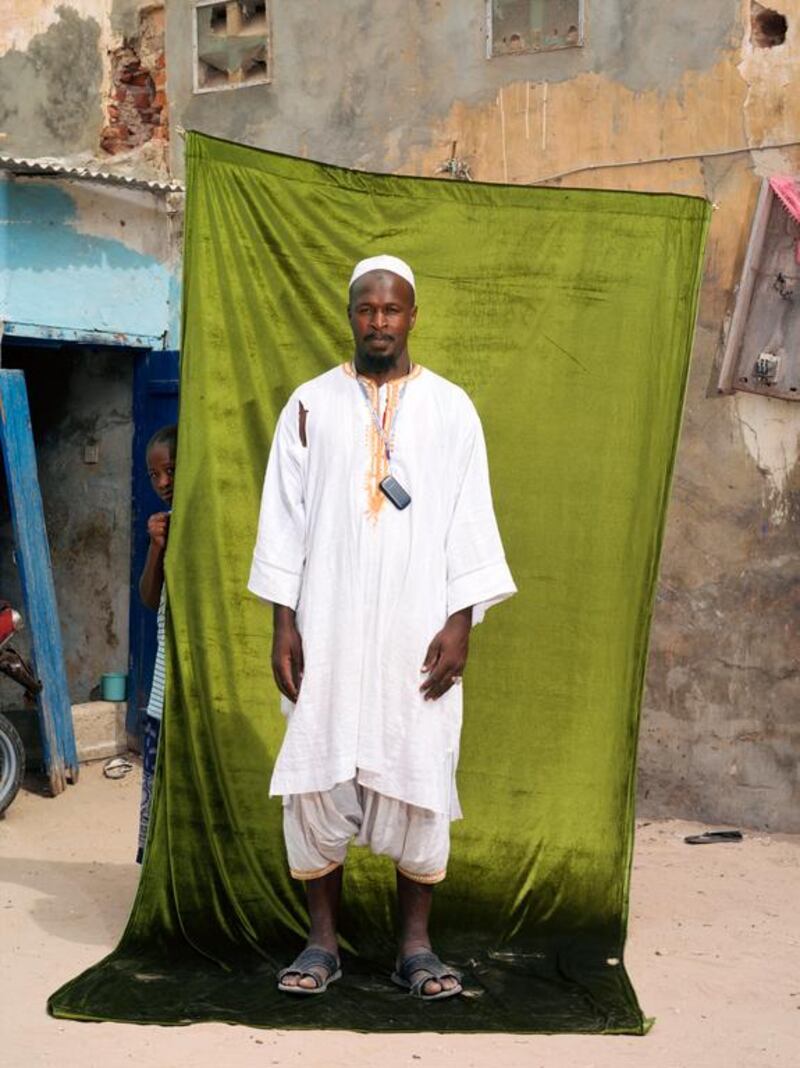

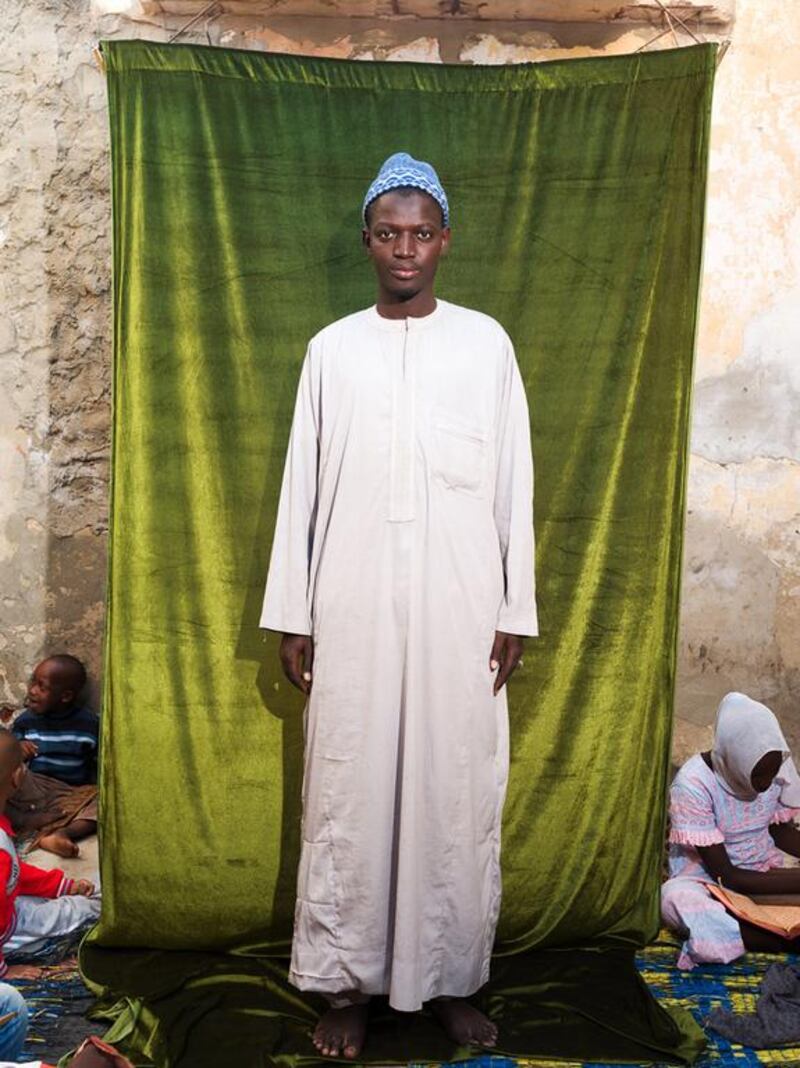

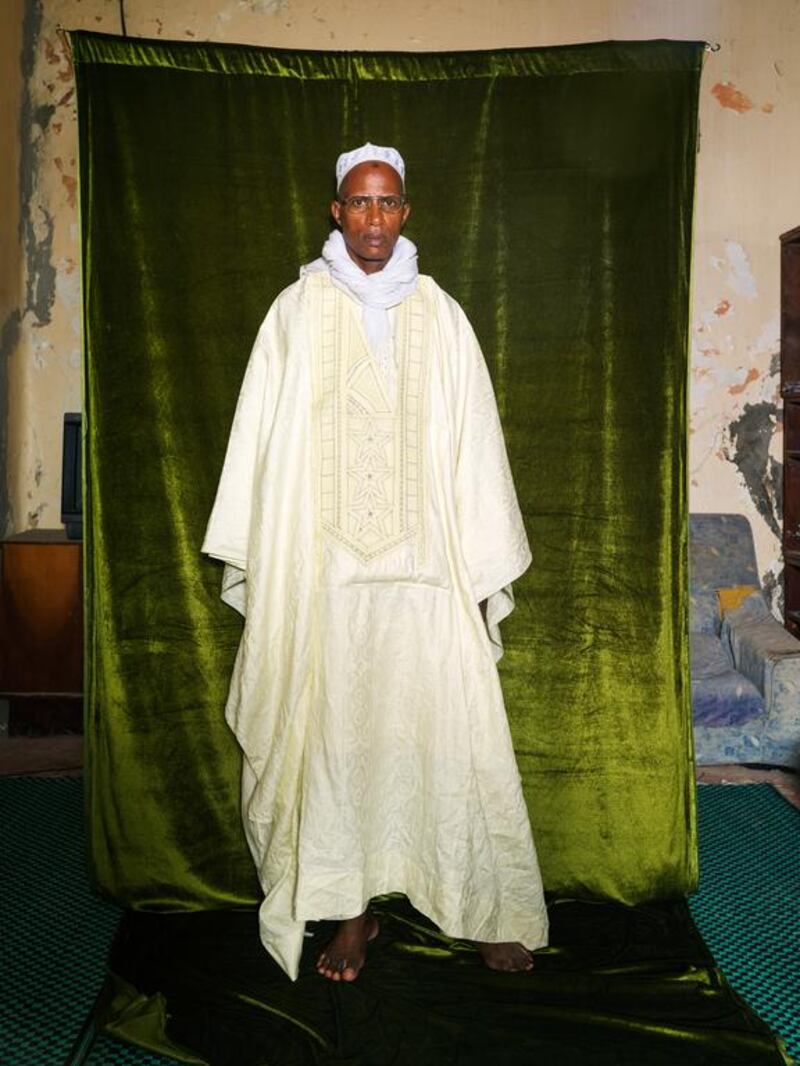

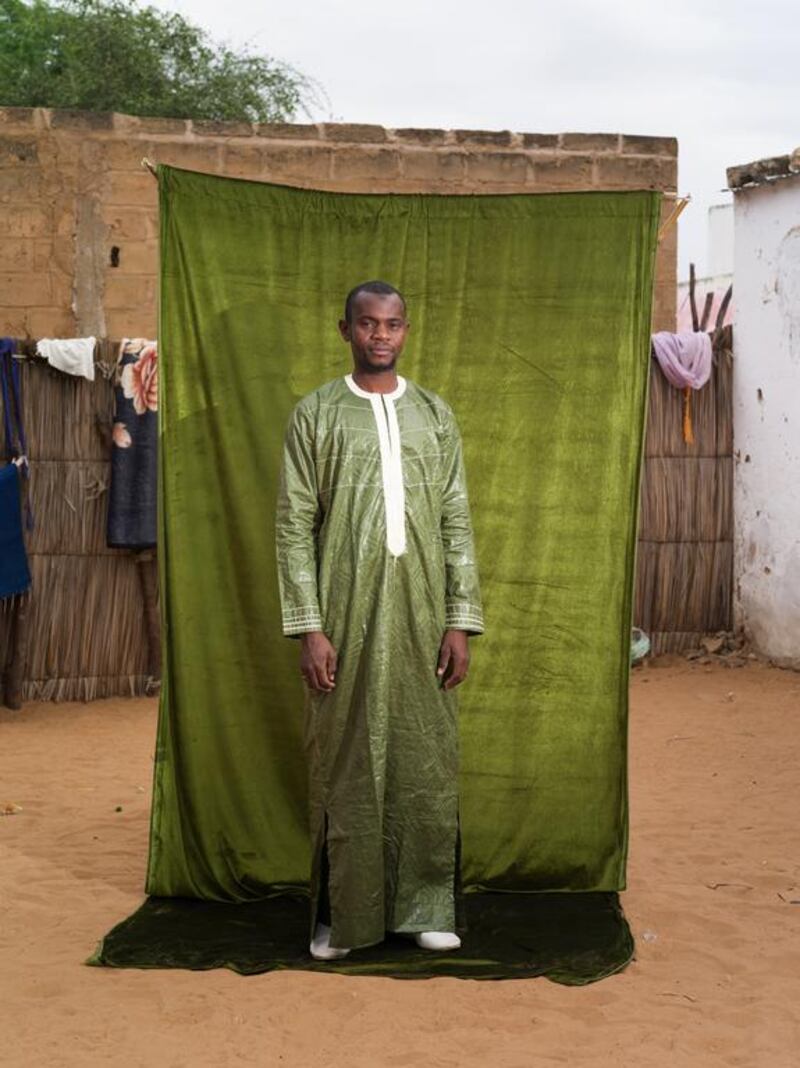

In Senegal, one of the most religious countries in the world, the marabout shapes society from the local, neighbourhood level up to national level. Raoul Ries’ series of marabout portraits illustrates the presence of these community figures in the neighbourhoods in which they work as Koranic teachers, mediators, and as a spiritual guides.

The Senegalese government does not pay for religious education, so the marabouts rely on donations. Sometimes the community provides these funds, yet more often the talibe, or students, have to gather daily contributions for tuition and board. Although laws against forced begging exist, attempts to regulate the Daaras, the Koranic schools, have so far been unsuccessful. As no minimal set of either educational or hygienic standards is in place, the situation of the talibe depends entirely on the marabout’s goodwill.

An interview between photographer Raoul Ries and The National assigning photo editor RJ Mickelson. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Can you describe what a marabout does (responsibilities, lifestyle, etc.)?

Two categories of marabouts live in Senegal: the healing marabouts and the teaching marabouts. The healing marabouts seem to focus on esoteric methods aiming to improve their customer’s health is some some way whereas the teaching marabouts are religious leaders and educators. The marabouts I met were in Saint-Louis were the latter, as they taught the Koran to boys and girls between six and twelve years of age. Many said they were also advising people from the neighbourhood in spiritual and practical questions. Several marabouts told me about Sufism and the specifics of the Tidjane and Mouride brotherhoods. Most talks with them revolved around ethical values and their influence in the community and they mentioned the practical aspects of leading a daara, which is a koranic school hosting between twenty and more than a hundred pupils. Although I met some marabouts in their homes, most photographs were taken near a daara. Most meetings lasted between half an hour and four hours, including the set-up and taking of the photographs.

How did you first learn about the Marabout?

I spent one month as an artist in residence at Waaw in Saint-Louis (http://waawsenegal.org/). Before travelling, I read as much as I could about the place and came up with a vague list of possible subjects for a photographic project, and the marabout was one of them. The ubiquity of talibe children in the streets made me want to develop that specific subject.

Can you describe your access to the Marabout community? Did you have a fixer?

As a stranger, I indeed required someone to introduce me to the marabouts. The people working at Waaw, and locals visiting the residency were most helpful. They arranged several meetings, and translated from French to Wolof or Pular when necessary. Even with their help, a few marabouts preferred not to participate in this series.

What were the biggest challenges when shooting the project?

The marabouts were in general well aware of photography’s power. Clichéd images made by tourists and the often stereotypical representation of Islam in Western media created an initial reluctance to being photographed. As some marabouts in Senegal received bad press due to child exploitation by a few of them, the people participating in this project were keen to know my intentions with this images. I explained that I wanted to photograph the neighbourhoods where marabouts lived and practiced, as they collectively shape an important part of Senegal’s culture. I did not want to search for visual, social or political extremes. While I developed my chosen method of working, it occurred to me that I came up with a way of showing one aspect of Islam in a truthful manner, and that the result was actually quite far from the ideologically motivated images adopted by some Western media. This fact opened doors for me, as the marabouts were keen to contribute to a peaceful image of their communities, and by extension of Islam.

Why did you decide to the felt backdrop but still allow the background environment?

As soon as I knew I wanted to take photographs of marabouts, I needed to find a coherent and meaningful way of working. Thinking about what would actually be important in these images I came up with three aspects: the marabout himself, a reference to Islam, and the neighbourhood influenced by the marabout. As green is often seen as the colour of Islam, I chose the most luxurious green cloth I could find as a backdrop. The rest of the set-up is improvised. It requires one person to uphold it behind the marabout. I wanted to somehow include glimpses of the children depending on the marabout as well. This device gave a pretext of needing children to help with upholding the cloth – a practical a symbolic gesture. Visually, the backdrop isolates the marabout and the environment as two co-dependent subjects. During the shoot, I concentrated on the portrait and life went on in the background. I also wanted to hint at some of Senegal’s photographic history and its past and current masters as well. Mama Casset, and today Oumar Ly used a similar background, although for different reasons.

Is this a project you’d like to continue and /or you interested in other stories on Islam in Africa?

Saint-Louis is a fascinating place, and I have more subjects that I would like to photograph. Several people also recommended that I continue my series in Touba, the holy city of Mouridism, and even offered their help as fixers. I feel that the marabout series can indeed be extended without visual redundancy, as they and their environments are so diverse. As I pay all expenses myself, I am in the process of looking for funders for a long-term project in Senegal.