What happens when one of the world’s foremost experimental artists wants to create his greatest permanent work in the UAE’s most conservative region?

Christo Javacheff hopes to do just that, and explained his innovative vision to Al Gharbia residents last week.

"The worst thing," Christo told an Abu Dhabi audience last week, "is a work that makes people indifferent."

There's not much chance of that, based on a career that has given him single-name recognition as one of the world's most avant-garde artists.

Christo was the guy who wrapped Germany's Reichstag in fabric, who created a 40km-long fence made of sheets of white nylon running across the hills of California into the sea, and who created 7,500 bright-orange gateways in New York's Central Park.

And he wants the legacy project of his 50-plus year career to be The Mastaba, a mammoth trapezoid of oil barrels in the desert of the Empty Quarter that will stand higher than the biggest pyramid in Egypt.

Indifferent? That's hardly a likely scenario, as Christo discovered when he and his entourage ventured to the western region to explain his dream to the residents there.

Al Gharbia is, arguably, one of the UAE's most conservative regions and not usually associated with avant-garde artists who live in Manhattan lofts and talk about creating works where the human reaction is as much a part of the art as the physical structure.

What do you think, one Emirati man was asked after Christo had explained how 410,000 barrels would be fashioned into the biggest sculpture the world has ever seen.

"It's crazy," he said, smiling.

"But I think you have to have that to build something like this. I think it will be a good thing for the region."

There are plenty of reasons to be perplexed by modern art but for this project, one aspect in particular stands out: Christo isn't seeking anything from the locals for the substantial cost of building The Mastaba, other than four square kilometres in the dunes north of Hameem and the permission of the authorities.

Nearly as baffling is that while the UAE is now associated with a range of record-breaking constructions, it has been considered as a location for The Mastaba since the early 1970s, not long after the nation was created. Now, it seems, The Mastaba is an idea whose time has come. During a question-and-answer session after the showing of a documentary about Christo's work at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival on Friday, he predicted a completion date of 2015. A firm decision about the project is expected to be announced in a matter of months.

Back when The Mastaba was first conceived, Abu Dhabi was hardly on anyone's radar, let alone that of the art world's cultural elite. Christo and his wife and collaborator Jeanne-Claude first visited in 1979 and found the perfect site beside what was then an unmade track through the desert.

The Mastaba was pushed on to the back burner while they pursued other projects which made their name, including the Reichstag, wrapping the Pont Neuf bridge in Paris, surrounding 11 islands in Miami with pink floating fabric, and The Gates in New York.

But Christo and Jeanne-Claude revisited the UAE until her death in 2009. Since then he has returned several times, most recently this month when he met Sheikh Hamdan bin Zayed, the Ruler's Representative in the Western Region, then lectured at universities and visited residents at Madinat Zayed, the nearest city.

At Khalifa University, he explained The Mastaba's provenance by showing how oil barrels had been one of his favourite media since the 1950s, most notably in 1962 when he built his own Iron Curtain, using 100 barrels to block a street in central Paris as a political statement against the construction of the Berlin Wall the year before. Critics described the ensuing traffic jam as the artwork, rather than the wall of barrels, which was removed after eight hours.

The artwork consisted of both the physical construction and the virtual one, involving the learning process required to achieve it and reaction of those who live in the intended location. For previous installations, he has faced death threats from outraged locals.

"Our projects are unique images. We'll never do another Gates, never surround another island. We know how to do it. That's the most important thing, that with each project, we don't know how to do it," he said.

"All our projects have a soft period when they exist only in drawings and sketches. Thousands of people try to help us and thousands of people try to stop us. You have 100,000 - a million - people thinking about a work of art that doesn't exist.

"It's why we don't do commissions, because the project creates the artwork.

"All these projects are totally useless, irrational and have no reason to exist. Nobody needs these projects."

So why Abu Dhabi?

"This isn't just anywhere. It's not like I'm closing my eyes and using my finger to choose Abu Dhabi. It was a matter of circumstance," Christo said.

"We tried Texas and never got permission."

It was the same with a sculpture park in the Netherlands.

"In 1972, we became friendly with the French ambassador to the United Nations. He said we should know about this country which has just become independent.

"Sheikh Zayed was very open and very visionary. But we knew almost nothing about Abu Dhabi.

"In 1974, there was an election and a new president of France, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, who nominated our friend as Foreign Minister. We said, 'Now we need to go to Abu Dhabi'. He arranged it with the French ambassador to the UAE.

"All our projects rely on circumstances and luck. That's why this project is so honest, because it happened that way."

Mastaba is an Arabic word meaning a mud bench and dates to Egypt at the time of the pharaohs. Once Christo and Jeanne-Claude travelled to Abu Dhabi, they discovered some of the locals were familiar with the word.

He drew his first sketch of The Mastaba, Project For Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, in 1977, imagining what the landscape might look like. The couple visited two years later, ruling out a potential location on the Abu Dhabi-Al Ain Road as too populated, then chose the current site on the road to Hameem.

"There was almost no road. It was one track," he said.

They returned to New York carrying sand from the Abu Dhabi desert and, more importantly, a definite vision for The Mastaba.

All their other major works had always been ephemeral, with the Reichstag, Pont Neuf bridge, surrounded islands, California fence and The Gates in Central Park all removed after two weeks.

The Mastaba, however, will be permanent. That augurs well for the Western Region, which will benefit both from the construction phase and then as The Mastaba opens and draws observers.

If there's one thing Christo is capable of doing, it's attracting crowds. Five million people visited the Reichstag during the two weeks it was wrapped. Four million visited The Gates in Central Park over a similar span.

An economic analysis has been done by Christo's team, although not released, but they will be hoping The Mastaba emulates the fortunes of a similarly extravagant piece of artwork, the Eiffel Tower, which was valued this year as being worth more than Dh2 trillion to the French economy.

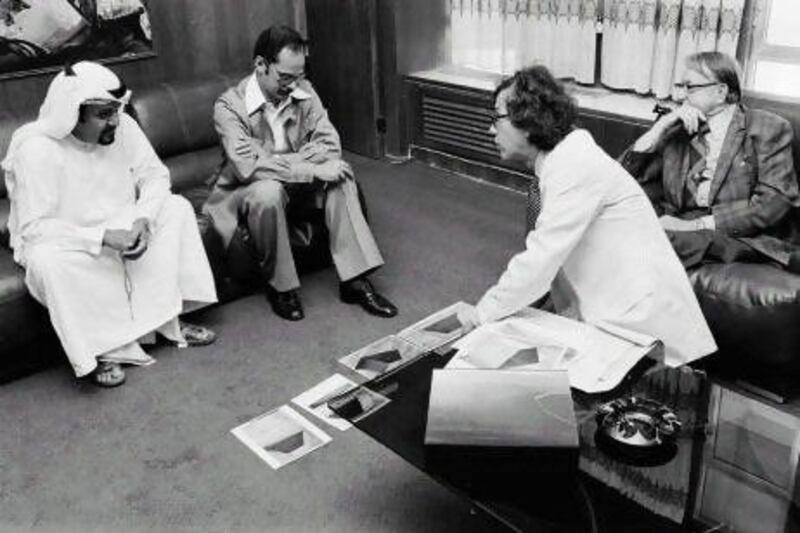

When Christo and his entourage travelled to Madinat Zayed last week to meet locals, they drove into the dunes for a meeting that seemed more of a photo op than consultation. For all that, there was genuine discussion.

"Why near Hameem?" one Emirati man asks Christo. "Why not near here? Can't we change the location? It's away from here. Not many people live near Hameem."

The unspoken part of the conversation is that this is the site he picked out with his late wife - and they slept there beside a scale model of The Mastaba to see what it was like in the dawn light. But he explains instead that the road to Hameem is being upgraded.

"You come to me tomorrow," the man responds. "We find location."

There is good-natured banter in which the man agrees not to be offended if Christo determines the dunes of Hameem are more attractive than the ones outside Madinat Zayed.

The group soon retire to the air-conditioned comforts of a majlis in town, where he used a lavishly produced hardcover copy of a book about The Mastaba to show a wider group of locals what is planned.

There's more discussion, especially about the orientation of The Mastaba in light of the prevailing sand drifts and the way its surroundings will remain completely natural.

"It's the wind," another man says, via an interpreter. "The sand will fill between the barrels. He's afraid that the project will be covered by sand, seemingly without appreciating that The Mastaba will be 150 metres tall, the equivalent of a 50-storey building.

"If you plant trees, it will be OK."

"No," Christo replies bluntly.

"No trees?"

"No."

The man who earlier described the project as crazy tells Christo: "We've never seen anything like this."

And Christo responds: "Artists always do things that people have never seen."