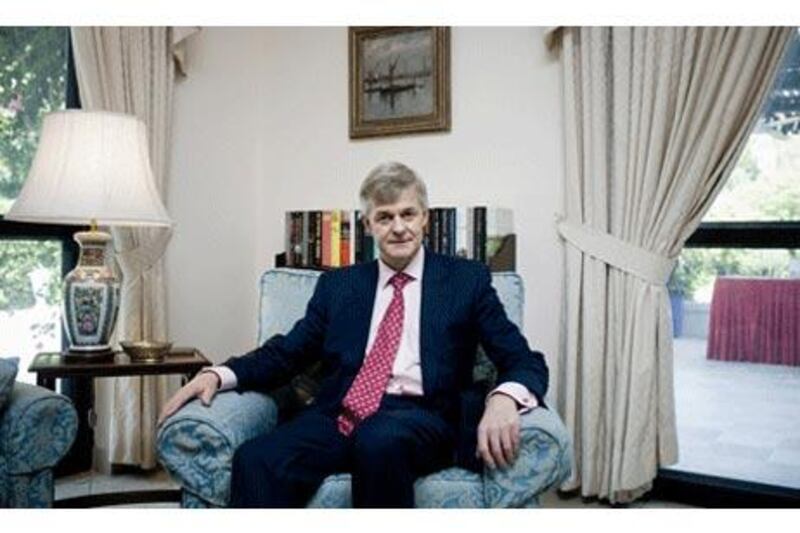

There are many questions for Edward Oakden, Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George and the British ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, as he packs his bags and prepares to depart these shores.

What is the current state of relations between his country and one of its oldest friends? How does Britain contribute to the security of a region vital to her national interests? Are companies from the UK competing effectively in one of the fastest-growing economies in the world? And then there is this one. How does he explain to his hosts why in recent months certain British newspapers appear to be mounting a vindictive and vituperative campaign against the UAE in general and the emirate of Dubai in particular?

But Mr Oakden is a diplomat and doing things diplomatically is what he does. So he knows exactly what to say when the phone on the ambassador's desk starts to ring furiously and high level figure of authority is on the line. "It is not my role to mediate," he says in a precise manner. "It is my role to explain. "I follow carefully what the British press say about the UAE, both for good and of the more critical elements."

While local sensitivities are inevitably hurt by the "one really critical article", it is "important to see criticism in context. Just because it is written in the press, it doesn't mean it is necessarily true and there will always be a range of opinions. Besides, there are plenty of articles saying nice things about the UAE." And so once again the ambassadorial high-wire act is successfully concluded. Mr Oakden has been the British ambassador since August 2006 and it is not flattery to say that he is as well-liked and respected in the majlis as he is in local boardrooms and the corridors of his own embassy compound.

Still, all things come to an end. There are 11 framed photographs hanging in the reception room outside his office beginning with Edward Henderson, ambassador for what was then just the emirate of Abu Dhabi from 1959 to 1961. Next month, Mr Oakden's portrait will join them on the wall. The sense of continuity cannot hide the huge changes that have taken place around the embassy compound in downtown Abu Dhabi. To negotiate the security barriers and massive blast gates that protect a modern 21st century embassy is to enter an incongruous world of immaculately clipped lawns and hedges set amid rows of colonial bungalows. At the same time, the concrete bulk of a skyscraper, its lower storeys already clad in polished silver, is rising above the perimeter wall. When the original embassy was constructed, it was just a few yards from the beach on land gifted by the rulers of Abu Dhabi. Land reclamation now means the new Corniche is a walk of several minutes.

Mr Oakden has moved from behind his desk, with its Union Flag and official portrait of the Queen, to a couch. Hanging on the wall above his head, an aerial photograph, half a century old, shows only one other recognisable building, the ruler's fort, now undergoing massive renovations. The two-storey embassy building still survives, arguably the oldest unchanged building in the capital. The role of the ambassador is also a mixture of old and new. The early envoys, from a time when the Trucial States enjoyed the protection of Britain's military might, were also kingmakers, most notably in negotiations for the transition of the rule of Sheikh Shakbut bin Sultan Al Nahyan, to his younger brother, Sheikh Zayed, in 1966.

It is not the role of British ambassadors these days to become involved in regime transition. Or as Mr Oakden, the diplomat again, puts it: "Times have moved on since the 1950s and the 1960s and the role of my predecessors was clearly appropriate to those times. "The role of the modern ambassador is fundamentally different to the one my predecessors played." In 2010, the British ambassador wears a variety of hats. With a staff of 400 in two embassies in Abu Dhabi and Dubai - the UAE is the only country where Her Majesty's government retains two embassies - he has a responsibility to one of the largest populations of British expatriates in the world (somewhere between 100,000 and 120,000; no one is quite sure) plus around one million tourists from Britain each year, who are generally well-behaved, but occasionally find themselves behind bars as a result of various well-publicised scrapes. Mr Oakden insists that the vast majority of his countrymen are well behaved, but admits, diplomatically (of course) that there are a few who are "not fully au fait with the cultural requirements of the UAE".

Then there is the flag waving for what politicians are overly fond of calling "Great Britain PLC". By the early 1970s the then Labour government's East of Suez policy effectively withdrew British interests from the Gulf, leaving the emirates to fend for themselves. There are many who feel that a historic relationship was damaged in the process, but those days now seem like ancient history. Or as the ambassador puts it: "That page has been turned."

The British invasion during Mr Oakden's time suggests a fleet of limousines in an almost constant convoy from the airport. He ticks the recent arrivals off on his fingers. "The PM twice, the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York, several times. There have been almost 60 high-level visits in the past year. Generally, a week does not go by when there are not several." He reflects again. "The Duchess of York, Tony Blair, Lord Mandelson, the Lord Mayor. It makes my life busy but it also makes my life focused and exciting." In this role, he describes the UAE and Britain as "two worlds spinning very fast". The role of the embassy is to be a "docking mechanism" that allows the right people to come together.

Asked about the future of the UAE, Mr Oakden shows an unscripted enthusiasm for what he calls "the growing strength of the federation". "When you talk to the younger generation and ask them if they are an Abu Dhabian or a Dubian, they look at you strangely and say 'I'm an Emirati'." Saying goodbye to his friends is, he says: "The hardest part of leaving. There is a warmth and depth to people here that I find very moving."

Pressed to describe what he is most proud of during his four years of office, he points to the partnership agreement between the British Museum in London and the new Sheikh Zayed National Museum on Saadiyat: "Something that I think will endure for many years." Still, surely there must have been times when relations between the UAE and Britain were tested, either for internal or external reasons? Mr Oakden, of course, does not rise to the bait. He prefers to refer to "bumps in the road" and avoids specifics. Some British businesses, for example, do not fully understand that they are not at the head of the queue when contracts are handed out.

"It is very important for business and government in the UK to understand how stiff the competition is here. Just as we would expect an Emirati to compete for business in the UK, so we need to be competing for business here. The way one won business 20 years ago is not the way to win business today." This view is something he will take to his next job, as one of the managing directors within UK Trade and Investment. His base will be London, where the current temperature is 4°C with rain. The weather is one more thing he will miss: "I love the heat. So I've been able to get out and do quite a lot of running over the past year." So, it's true about mad dogs and Englishmen then? "Well no, I don't go out in the midday sun. In the summer I wait until after dusk."

Time is up and the ambassador needs to get back to the hectic business of departure. A few weeks ago a delegation of sheikhs visited the embassy and made the surprising and generous gift of a baby racing camel. One suspects that for a brief moment, Mr Oakden considered the appeal of riding to his new job along London's Whitehall like a modern-day Lawrence of Arabia. "I was enormously touched by the gift, but decided that it would be better for the little camel to grow up with its peers in Al Ain."

As always, the diplomatic solution. @Email:jlangton@thenational.ae