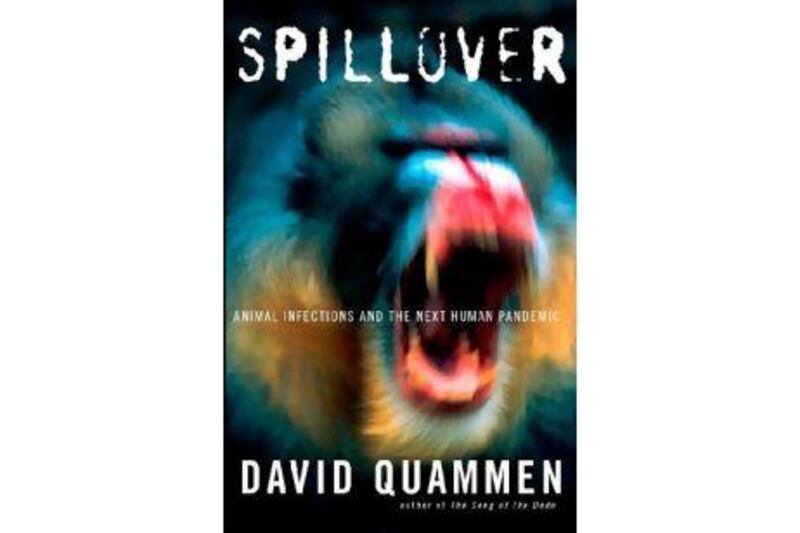

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic

David Quammen

WW Norton & Co

Fear scurried and squeaked its way into the Curry Village tent camp at America's Yosemite National Park in California last August.

Deer mice carrying the deadly hantavirus exposed tourists when they breathed in dust from the rodents' droppings. And the results were frightening: by mid-September nine people had been confirmed ill with the disease; and, tragically, three died. Nor did the danger end there, because thousands visit Yosemite's soaring mountains and cascading waterfalls each summer - and hantavirus's incubation period can last up to five weeks.

Of course with such zoonotic diseases - meaning those that jump to humans from wild animals - the danger never really ends because wildlife can't be controlled.

And, worse, these pathogens are on the rise. This past summer, again in the United States, West Nile virus - causing 1,121 cases and 41 deaths - hit its highest peak ever. From Uganda came reports of at least 20 cases of Ebola, and 14 deaths, including a rare urban case in Kampala that caused widespread panic. In the Middle East, a coronavirus killed a Saudi national and left a Qatari man fighting for his life; and that virus turned out to be a biological cousin to China's Sars epidemic in 2003, which infected 8,098 and killed 774.

Why are we seeing so many clusters of death now? Science writer David Quammen tackles that question in his impressive, big (520-page) book Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic. And the culprit he puts forth for the zoonotic trend is humanity itself.

"We should appreciate that these recent outbreaks of new zoonotic diseases, as well as the recurrence and spread of old ones, are part of a larger pattern," Quammen writes. "Humanity is responsible for generating that pattern. We should recognise that [these outbreaks] reflect things that we're doing, not just things that are happening to us."

What we're "doing" starts with the growth in population - the simple fact of seven billion people on Earth makes us "grotesquely abundant", Quammen says, and available to the six classes of pathogens: viruses, bacteria, protists, fungi, prions and worms - viruses being the worst. Our increased density offers another benefit. So does the fact that "we have penetrated, and we continue to penetrate, the last great forests and other wild ecosystems of the planet, disrupting the physical structures and the ecological communities of such places", he writes.

Shaking the trees makes things fall out, he continues, and exposes us to new dangers. So does eating an ever-expanding list of wild animals; operating factory-style livestock operations; increasing our global imports and exports; travelling more internationally; and altering the global climate with more carbon emissions, which in turn broadens the latitudinal ranges for disease-spreading mosquitoes and ticks. "Evolution seizes opportunity, explores possibilities, and helps convert spillovers to pandemics," the author points out, emphasising that in his view, epidemics are not an act of God.

What makes Spillover (the technical term for the moment when a pathogen passes from one species, as host, into another) particularly compelling is the journey it takes readers on into the rarefied world of disease ecologists, whom Quammen visits across four continents, watching and taking notes as they probe the secrets of Hendra, Ebola, Lyme disease, herpes B, Nipah, Marburg, H5N1 (bird flu) and Aids.

Disease ecologists spend a lot of time pondering how these diseases arise, which animals serve as their reservoirs (the animals that carry pathogens without threat to themselves) and which are their vectors (deer ticks spread Lyme disease, for example). These disease detectives also worry profusely about the Next Big One - the next pandemic - because relatively recently, we've seen Aids kill 30 million, and Spanish flu in 1918-1919 kill up to 50 million (not to forget the Black Death, which in 1348-1350 wiped out more than one third of Europe's population after travelling along the Silk Road from China).

What has kept the human race alive (for now) is the fact that spillover diseases (comprising 60 per cent of the infections affecting us) typically have limited virulence. Ebola, as terrible as it is and was, killed a relatively small number, 224, during its 2000 outbreak in Uganda. Infected humans can be quarantined, and can thus be a "dead-end" host. So Ebola can be contained. But there's still that Next Big One out there, Quammen warns, providing a cautionary tale from his own youth in Montana, where in 1993, an explosion of tent caterpillars - poof - came to a sudden halt. A pathogenic virus had ended them, Quammen notes.

He had to wonder if we would be the next caterpillars.

What makes for great reading here is the author's adventures in the far corners of the globe, where he talks to the frontline researchers, who often work at great personal risk. Tagging along with Quamman, we visit the "monkey temples" of Bali, where macaques frequently interact with tourists, resulting in bites and scratches - virtually all these monkeys carry dangerous herpes B. In China, we learn about the "Era of Wild Flavor", popular at the time of the Sars outbreak, which encouraged Chinese to dine on an eye-popping range of animals, from domestic dogs and cats to toads, lizards, snakes and bamboo rats - not because those eating them were hungry but because it was trendy. Unfortunately, the "wet market" of Guangzhou also sold civets, later discovered to be an "amplifier" of the local Sars outbreak.

In Malaysia, we learn that giant bats taint local date palms with Nipah virus - which humans then pick up when they consume the trees' sweet sap. In Gabon, we hear of 13 gorillas found dead together, probably due to Ebola; we then accompany Quammen through the eerily silent forest, now devoid of the big apes. We learn of 18 people there who became sick after butchering and eating a chimp; and in Cameroon, we hear about a bizarre coming-of-age ritual for boys of the Bakwele tribe that involves cutting off and consuming the arms of chimpanzees - which are often infected with SIVcpz, or simian Aids.

"Throughout the rest of the world you see Aids-education materials crying out: Practice safe sex!" Quammen comments ruefully. "Here [in Cameroon, where public health posters warn against eating bushmeat] the message was 'Don't eat apes!'"

The point, of course, is that there is an intermediary virus that transmutes SIVcpz into human HIV; that intermediary was first found, Quammen notes, in Senegalese prostitutes. In one of the book's most fascinating passages, he relates how researchers genetically tracked the first Aids spillover from a chimp to a human - probably via butchered meat - around 1908. Most people, the author says, don't know that the Aids story didn't begin with American gay men in the 1980s, or in African cities in the 1960s, but "at the headwaters of a jungle river called the Sanga, in southeastern Cameroon, half a century earlier".

The writer tells many such amazing stories about the pathogens that plague us. Who knew that Aids crossed over into Haiti because the Belgians' departure from the Congo caused a mass exit of local professionals that Haitian doctors and teachers were only too happy to fill?

Who knew white-footed mice, not deer, are the most efficient reservoirs for Lyme disease?

Not that deer are blameless in breeding ticks. "A whitetail in the woods of Connecticut during November is like a teeming singles' bar in lower Manhattan on Friday night," Quammen writes, in one of the many witticisms he injects to make his survey of death and destruction more digestible. He's particularly jovial explaining dry scientific concepts like the particle hypothesis of disease, density theory, and something called R0 (the reproduction rate of new infections from an infected individual). Some of his jokes take flight; some fall flat.

But, in the end, there's nothing funny about the horrors of bloody Ebola or the pandemic threat posed by the H5N1 bird flu. Spillover is a grave and scary book, enough to make us put our affairs in order and kiss our loved ones goodbye. Enough to make us hope that the Next Big One doesn't occur anytime soon.

Joan Oleck is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn, New York.