Lebanon’s capital Beirut has a reputation as the Middle East’s party city, but this reputation has a flip side – widespread drug use among the country’s youth.

Walk into a toilet in any of the city’s clubs and it is not uncommon to see people snorting cocaine or popping pills containing substances such as MDMA, also known as ecstasy.

While middle class partygoers might dish out up to $100 for a gram of coke, cheap opioids such as heroin and tramadol, as well as the amphetamine-based captagon, have become increasingly common.

The Arab Youth Survey, commissioned by the Dubai communications agency Asda'a Burson Cohn & Wolfe, was released on Tuesday and this year included drug use data for the first time.

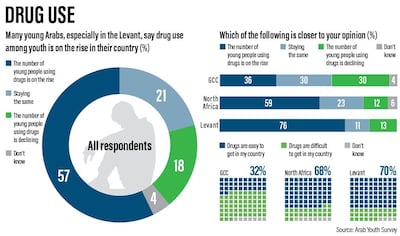

It found that 76 per cent of young people in the Levant – which includes Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and the Palestinian Territories – think drug use among the youth is on the rise. That is far higher than in rest of the region, with 59 per cent in North Africa saying that they are seeing an increased amount of drug-taking and 36 per cent in the GCC.

The majority of Levant’s young people, at 70 per cent, also said that drugs are easy to get hold of in their country, with 68 per cent agreeing in North Africa and 32 per cent in the GCC. Lebanon, in particular, has for years been a hotspot for drug use and production.

“Drugs are very easy to buy in Lebanon,” said Sandy Mteirik, drug policy manager at Skoun, a Lebanese addiction treatment centre.

According to a 2017 report published by the country’s Ministry of Health, there were 3,669 arrests for drug use in 2016, three times higher than in 2011. The Lebanese are also consuming drugs at an increasingly young age, with the number of arrests of people under 18 more than tripling during the same period of time.

A key contributor to this rise is thought to be Lebanon’s own hashish and opium production in the Bekaa region, a fertile agricultural valley that lies on the border with Syria.

Taking advantage of the weak state, drug lords have openly produced and traded cannabis since the end of the civil war in 1990, despite both being illegal. Although politicians have talked about legalising cannabis for decades, little has come of it and drug use or possession is punishable by up to three years in prison and a fine.

Estimates on the level of production vary wildly. A 2018 report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime said that 3,500 hectares of cannabis were cultivated in the country in 2015, but the Ministry of Health put that figure as high as 20,000 hectares in its 2017 drug report. There are no statistics regarding opium production.

The health ministry also claims that hashish is sold for a little over $1 a gram, explaining in part why it is the most popular recreational drug. The most common drugs seized by the authorities are cannabis, and the non-locally-produced cocaine, Captagon and ecstasy. The latter are smuggled through the airport or the porous Syrian border.

Captagon, sometimes referred to as “chemical courage”, made headlines when it became popular among fighters in the Syrian civil war – it is considered to improve alertness and combat effectiveness.

Despite drug usage being common, it remains stigmatised by Lebanese society and the media. This week, Lebanese daily Al Akhbar reported that a 70-year old pharmacist in Beirut was attacked by a drug addict wanting tramadol, an opioid-based painkiller. A former heroin user told us that when heroin is unavailable users turn to tramadol, which is known as farawla, or strawberry, in Lebanese Arabic because of the pill's red colour.

Heroin is cheap, however, costing between $10 and $30 a gram, making it popular among the working class, but its usage is more heavily stigmatised than cocaine.

“Some people start with coke and run out of money and turn to heroin. I don’t like it [heroin] – it is dirty”, said Fadi – who did not want to give his full name – 34, a regular cocaine user from Beirut’s southern suburb of Dahieh.

The Arab Youth Survey found that in most cases, drug consumption begins with encouragement from friends, and a number of recreational drug users who spoke to The National agreed.

Fadi said that he started taking cocaine to stay awake while consuming large quantities of alcohol. “Now every time I go to a club, I can’t enjoy it without coke,” he said.

Over the past 10 years, he estimates that he has spent about $100,000 on the drug. He has managed to avoid arrest so far, something that is by all accounts a very unpleasant experience.

A 2013 Human Rights Watch report revealed that those detained by security forces are routinely tortured. Well-connected detainees may secure favourable treatment through personal or familial connections, locally known as having a "wasta", or a contact. The services of a lawyer, even for minor offences such as carrying a marijuana joint can cost several thousand dollars.

The law states that judges cannot prosecute drug users who ask for treatment and must refer them to the state-funded Drug Addiction Committee, but only 4 per cent of cases were referred between 2013 and 2016.

“The authorities are very tough on drug users. They are subject to human rights violations and not granted the right to treatment as stated in the law”, said Mrs Mteirik.

While the Ministry of Health charges for medicine to treat opioid addiction, making it a difficult option for those from underprivileged backgrounds, NGOs such as Skoun deliver therapy for free.

While users often complain about the state’s punitive attitude towards them, arguing that it should do more to crack down on the dealers instead, their complaints don’t appear to have been heard. One of the country’s most notorious drug lords, Noah Zeaiter, gave several lengthy television interviews in 2016, including with the state-run Tele Liban. Wearing a black cowboy hat, he argued that, like the famous Columbian drug dealer Pablo Escobar, the money he makes pulls people out of poverty.

Mr Zeaiter still lives freely in the Bekaa.