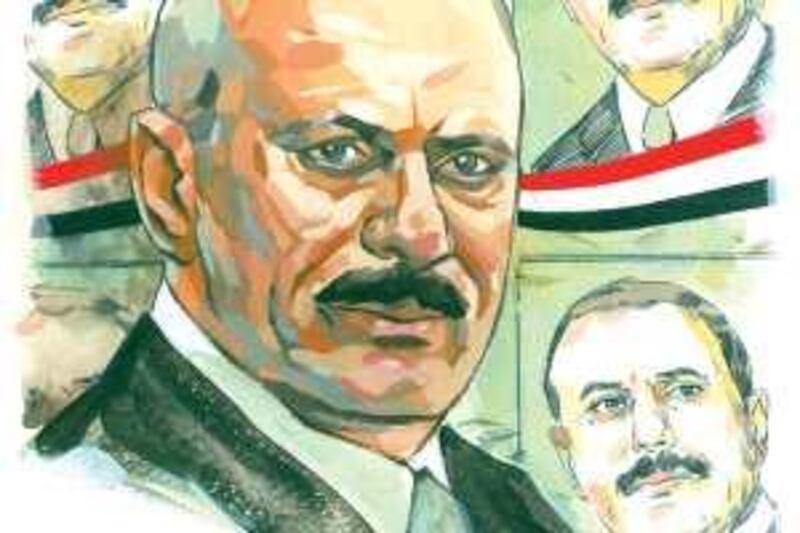

To casual observers, it might appear that Yemen, which seems to slip off the radar except when it somehow disturbs the outside order of things, cannot get out of the news recently. The reach of the country's central government in Sana'a appears to be diminishing; troops fight rebellions in the north and south; and Yemen-based al Qa'eda militants are trying to wreak havoc. Amid what increasingly looks like looming disaster stands the President of Yemen, Ali Abdullah Saleh, who has seen his country swiftly brought to the world's attention, with recent events conspiring to make Yemen the new front - publicly, at any rate - in America's global War on Terror. At the same time, Saleh himself is seen as the latest international latest poster boy for the fight against jihadis

The attempt to blow up Northwest flight 253 as it started its descent over the Great Lakes towards Detroit last month, and the Fort Hood shootings in Texas in November, both appear to have Yemeni connections and speedily focused minds on a part of the world that many fear risks sliding into failed state status. President of the republic for some three decades - spanning the years before and after the 1990 unification of modern Yemen - and widely regarded as a shrewd political operator, Saleh has nevertheless been mired in a political crisis so deep that many may wonder how Yemen, on the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula, has not already gone the way of Somalia, its lawless and broken Gulf of Aden neighbour.

The 67-year-old has been continually at war with both the north of the country, where a Shiite sect called the Houthis, centred in the town of Saada have been engaged in an all-out war against the government for almost a decade, and the south, where nationalist agitators, many of them remnants from Yemen's civil war have resumed pressing for separation. With oil revenues eroding fast, agriculture waning and unemployment skyrocketing, it is little wonder, on the face of it, that Saleh has called for greater support from the US and his neighbouring states to step up their efforts and assist in rooting out known Yemen-based al Qa'eda operatives. Until now, such support has been relatively paltry: the US last year only financed Yemen's counter-terrorism operations to the comparatively small tune of US$70 million (Dh257m), while Saudi Arabia contributed a hefty $2 billion and the UAE $650 million.

Some analysts have suggested, however, that al Qa'eda is, compared to the country's other problems, little more than a persistent nuisance to the beleaguered president, and that the will to fight the group head-on is indicative of a politician who has maintained his grip by hedging his bets. Even so, in the aftermath of September 11, Saleh took a practical worldview and embraced America's stance on terrorism. He flew to the White House to make clear his pro-Washington stance and his desire to co-operate, and even allowed American drones to kill high value militants on Yemeni soil.

Although the joint US-Yemeni effort to kill off high-ranking al Qa'eda members in the country and dismantle its power base met with some success immediately after 9/11, Saleh's history of turning a blind eye to Islamic extremists for his own political ends, and his penchant for paroling figures wanted by American prosecutors on terrorism charges, has led many in the US to question the wisdom of relying on him.

In order to understand Saleh - and the fragile country which he has led since 1978 - one must understand his past. Born into a small tribal peasant family in 1940s Bayt al Ahmar, near the capital Sana'a, Saleh joined the army when he was 16 and quickly forged a successful path as a career soldier, eventually reaching the distinguished rank of field marshal. According to his official website, Saleh led an almost heroic existence in the army, joining "all battles before the revolution in different areas of Yemen" where "he was one of the heroes in the 70-day war when Sana'a was under siege."

Such was his rise through the ranks that it was, perhaps, little surprise that he ascended to the role of president of North Yemen in 1978. By then, the country was already racked by two decades of civil war and unrest, and, having assumed office hot on the heels of his two slain predecessors, Saleh might have been forgiven for seeing the Presidency as something of an unfortunate job with a short lifespan.

Indeed, many thought that Saleh's days would be similarly numbered, but he proved to be made of sterner stuff - a survivor of the highest order. Not for nothing has he carved out a reputation as a wily operator, promoting family members to powerful positions in public office and consolidating his hold. In 1990, Saleh presided over the unification of North Yemen and the Marxist south. Four years later, however, the country fell back into civil war as relations between both sides of the divide quickly deteriorated.

During the conflict, Saleh used the thousands of unemployed and battle-hardened Arab militants he had welcomed back from Afghanistan several years earlier fresh from their rout of the Soviet Union. After two months, the fighting was over, with the south's secessionist leaders defeated and forced to flee abroad. But, for Saleh, the die was cast, and his decision to play political games led him to use the anti-US Islamist extremists in the north as a means to counter threats posed by Houthi rebels.

The Houthi rebels are members of the Zaidi Shiite sect, a group with which Saleh himself shares some heritage in this Sunni-dominated state of 23 million people, as if to underline the complex nature of the situation as well as the president's unashamedly pragmatic approach to ruling his ailing country. Despite letting some democratic structures grow - not least a multiparty system and semi-regular elections - Saleh has increasingly faced allegations that he has hampered Yemen's development through a patronage-based system of government laden with corruption.

His critics say he has been too focused on securing his family's power base at the cost of many wide-ranging of Yemen's social and political gripes and grievances, squandering opportunities to settle the disputes raging in the north and south of the country. So, what of the future? Well, as the US looks to the veteran politician, who, according to London's Daily Telegraph, is one of the longest serving rulers in the world, he will need to summon the capabilities that made him field marshal and prove to the outside world that when it comes to al Qa'eda, and Islamic extremism in general, he cannot only talk tough, but can also act tough.

There are countless flies in the ointment, however. Firstly, there is the challenge to his own authority, and to that of his son, Ahmad, who, it is widely reported, is hoping to be anointed president after his father's term of office expires in 2013. They include Hamid al Ahmar, the leader of Yemen's strongest opposition group, the Islah party and a member of a powerful family who, despite Saleh's attempts to keep him onside, last year announced the near 70-year-old president had outstayed his welcome and should not try to install his son.

Secondly, there are the possible consequences of acting on America's orders to strike al Qa'eda in Yemen, with a wide swathe of the Yemeni public and many public figures sympathetic to the group, and who would not support him in the battle. But Saleh, who once described ruling Yemen like "dancing with snakes", is nothing if not bold and calculating, and while his efforts to manage both the Americans and the jihadists have stalled of late, his recent political revival in the eyes of the international community has underscored that he is not to be underestimated.

* The National