The rain is coming down especially hard and the frantic birds are looking for cover. It is literally the loudest thunder I've heard in my life. I pull aside the curtain in the bedroom and watch the rain hit the panes and look for the workers who are building the house opposite. They are inside and from what I have seen, these workers are at least well-fed. The Commonwealth Games are less than two weeks away and here in New Delhi there is no way to miss the poor hard at work on the roads in preparation for the Games.

What is easier to miss is that more than 70 workers have died in construction-related accidents, according to an independent Human Rights Law Network report. It is at these moments when my heart aches the most for the poor living in the slums of Delhi. We are in the car, as it wades through two feet of accumulated rain water in street bends in Jangpura, safe and sound. I had wanted to take an auto rickshaw but those will have a hard time today.

We had wondered about what would happen to the poor during the monsoon rains. Now we know. Now I wonder about those thin rags that are called clothes that the poor wear and how exactly they will shelter the wearers from the cold. There used to be humidity with the rains but now the temperatures are dropping. Under the bridges and on the medians, children wander while men sit with their childlike limbs, staring into nothing. There are no traffic-light beggars because the weather is too bad.

We had not previously noticed the blue canvas tents erected alongside pavements by the dozens. Apparently, they are left over from construction. Some stones are gathered to make for a makeshift stove upon which an open pot sits. You have to wonder what exactly they are going to eat. In Arabian tales of old, the poor would boil water with sugar and, very simply, eat that. I can't help hoping they are eating something more substantial.

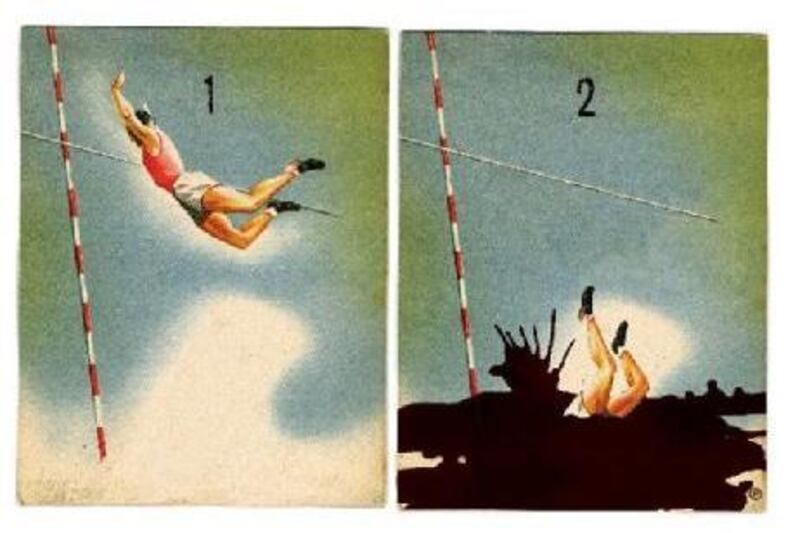

It used to be that every time I saw a mutilated person I would remember reports of the mafia gangs who are said to inflict permanent injuries to children to make them effective as beggars. While I am sure that is true (we used to see a lot of those in Makkah) I must think now of the many very real and probable calamities that have happened to the Commonwealth workers. Since most have no hard hats, no boots and no gloves, such injuries are bound to happen. If you lose a foot or a hand, you have lost an essential limb to make your livelihood.

Every working day my husband would look down during his lunch hour at a man who sat motionless for most of the day. The only time he moved was when he was hungry. My husband would watch him lumber across the street, uncaring for the traffic and the angry drivers, moving at his own pace, only stopping when he came upon a food stall. There he would watch until someone took pity upon him and gave him his day's food. When that was done, the man would make his way back to his spot and sit there once again.

After hearing anecdotes like this, I cannot be surprised that workers toil under such miserable circumstances: about Dh8 for a day's work, no paid day off and no accommodation. One female worker was burnt, according to the human rights report. She was paid less than the men; even at such a low wage, discrimination is alive and well in every ladder of society. Our taxi driver, Shishpal, told us he once drove an Australian reporter to a group of workers and asked him to interview them for her, doubling as a translator as well as driver. Some would speak, others did not and still the police came and caused trouble. Shishpal refused to take her again for fear of repercussions.

He told us he was thinking of buying a new car and upgrading. Shishpal stashes his daily money diligently and can afford the upgrade. His colleagues at the taxi stand made such fun of him for trying to move ahead in the world that he seriously re-thought the idea. It was as though their cynicism had got to him and, well, how could it not? Once, on a trip to Rome, I experienced a small culture shock after seeing a woman in full garbage worker's clothes and cap working on the streets. I had always thought that sort of work, especially outside an enclosed environment, would be too harsh for a woman. I suppose that makes me a bit sexist but I still think this. It's not that I think the woman wouldn't be physically able to take it, but that basic feminine pride wouldn't permit such a thing.

Obviously, I've lived a comfortable life, thanks to the Emirati government. Free education, free housing, free healthcare - they are the basic necessities of having a decent life and I will forever be grateful to my country. If I wanted to work I could, and if I did not, well, then I could afford not to, thanks to my father or my relatives or my husband, after my marriage. Over the months I've lived here, I have seen these worn women on the streets, surrounded by their children even at the construction sites where they work, heaving great amounts of cement upon their heads in rusty metal bowls or sitting in rows making slabs under the unrelenting noon heat. I wonder if the harsh rains have made them sick. I wonder about their children and how vulnerable they are. I am angry that they still reproduce, but is it not a basic human right to want children? So how am I in any position to judge them?

It would be wrong, also, to pour all my sympathy on the women, since men make up the majority of workers. I suspect the reason why the men's meagre pay is slightly higher is because they have families to take care of, but this is just a guess since most recruitment officers are reluctant to give interviews. How they summon the strength to work seems a feat in itself to me. With no proper nourishment, no accommodation, no protection from the elements, no electricity and no toilets, you wonder how they made it at all.

There have been approximately 150,000 labourers working to prepare the Games, but this is just a fraction of the poor. They work overtime constantly without extra compensation. The workers come from the states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Bihar and Orissa, yet most of them have no displacement allowance. What was once a great achievement for India, to host an event on this scale, has fast turned into an embarrassment. There is still debate as to whether the Games are going to be held at all, while the allegations of corruption come from critics both local and international. Long after this issue has ended, though, the deaths and unaddressed crippling injuries will remain as part of the legacy of the 2010 Commonwealth Games.

Iman Ali is an Emirati national who is Zayed University's last known English literature graduate. Raised in Scotland, she graduated in Abu Dhabi and is currently writing The Great Emirati Novel.