SYDNEY // In February 1968, a quarter of a million people lined the streets of Melbourne for a glimpse of Lionel Rose on his return from winning a world boxing title in Japan. The size of the crowd was extraordinary - not least because Australia's newest hero was a young Aboriginal man.

Less than a year earlier, Australians had, by a large majority, voted in a referendum to amend the constitution to recognise Aboriginal people as citizens. Until then the country's approximately 100,000 indigenous people had been officially classed as part of the country's flora and fauna.

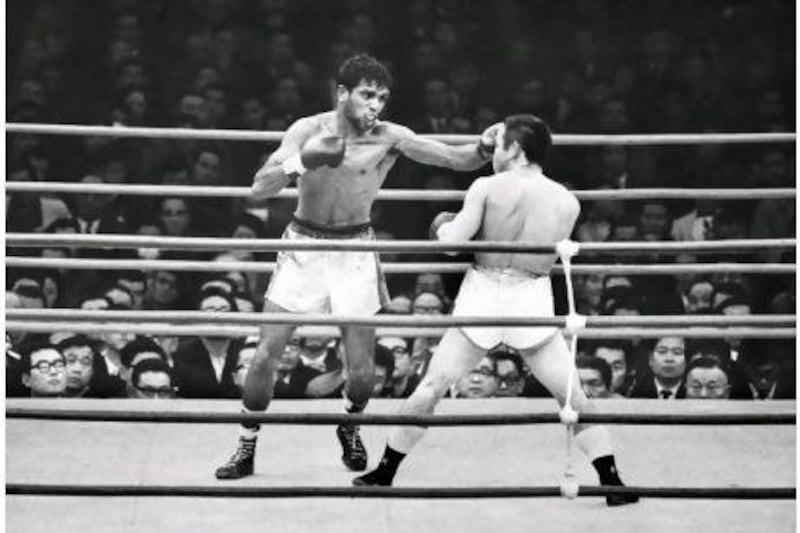

There was a new mood of optimism in race relations, with hopes that the referendum represented the first leap on the road towards equality between black and white Australians. Rose's stunning victory, at the age of just 19, over the legendary Japanese boxer Masahio "Fighting" Harada, seemed to capture that spirit.

A few months later, Rose - who died a week ago, aged 62, after a lengthy illness - became the first Aboriginal Australian of the Year. He was also made an Member of the Order of the British Empire

It was a remarkable achievement for a young man who grew up in a dirt-poor fringe community in Victoria, boxing with rags tied around his hands, in a makeshift ring made of chicken wire stretched between trees.

Many elite Aboriginal athletes have named him as their inspiration, but he also motivated people outside the world of sport. "Lionel Rose showed indigenous Australians that they could achieve anything if they worked hard," Johnny Lewis, a leading Australian boxing trainer, said last week.

Rose won his first major fight in 1963 at Melbourne's Festival Hall, where he is to be honoured with a state funeral tomorrow. But it was not until he challenged Harada for the WBA and WBC bantamweight titles that he registered on the national radar. Although the odds were heavily against him, Australians huddled around their radios to follow the electrifying fight in Tokyo. There was no live television coverage then.

His win - attributed to his lightning speed and the pinpoint accuracy of his punches - earned him a place in the history books, and in the nation's heart.

"There had never been an Aboriginal sportsman of that stature, and suddenly here was this exceptionally good-looking, athletic person who was admired by everyone, and was an absolute role model for his community," says Terry Cutcliffe, a veteran indigenous rights activist.

Although courted by celebrities, including Elvis Presley, who insisted on meeting him when he defended his title in California, Rose remained a humble and quiet man. "He was a gentleman, and he didn't have a nasty bone in his body," says Gordon Syron, an Aboriginal artist and former amateur boxer. "When he beat Fighting Harada, I was so proud of him, as were so many Aboriginal people."

Rose did not campaign openly for Aboriginal rights - "We're all Australians," he told one interviewer - but he was one of the first sportsmen to boycott apartheid-era South Africa, refusing a lucrative offer to fight there in 1970. He also reportedly badgered politicians in private to do more for Aboriginal Australians.

The sad reality is that the expectations created by the 1967 referendum, and reinforced by Rose's epic victory in Japan, have to a large degree been disappointing. Although indigenous people won recognition of their land rights, they continue to be disadvantaged in every realm of life, including living conditions, work, health and the justice system.

More than a quarter of the prison population is black, although Aboriginal people make up less than three per cent of the population. Aboriginal men live on average 11.5 years less than their white counterparts. Rose went off the rails for a while after retiring in 1976, battling alcoholism and serving a brief jail term for petty crime. But in recent years he had rehabilitated himself in the public's eyes.

His legacy is that of a fine if flawed human being who did more than most to breach the black-white divide, and the excitement generated when he became a world champion was repeated in 2000, when Cathy Freeman won a gold medal at the Sydney Olympics.

Australia's opposition leader, Tony Abbott, said last week that although Rose was not a political activist, "few have equalled his efforts to bring about true reconciliation".