feminism

Last April in Paris, feminist activists from a group called Femen burnt what they described as a Salafi flag in front of a mosque. The public spectacle grabbed headlines because Femen activists always stage their protests by going topless. The young women had painted slogans across their naked chests. The most polite was “Freedom for women”.

The event sparked strong reactions, but not from the expected quarters. A call went out for Muslimah Pride Day. Muslim women from all over the world posted photographs of themselves on Facebook holding handwritten signs that said things like “Islam is my right”, “Freedom of choice” and “Nudity does not liberate me and I do not need saving”.

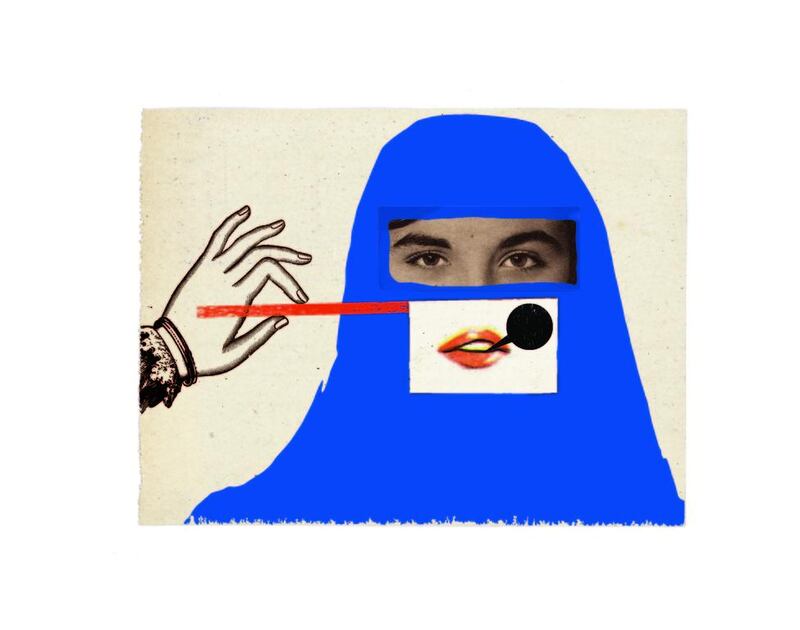

The counter-protest forces us to question the assumption that is taken for granted in Europe and North America – Muslim women are oppressed by their religion. This assumption makes everything from banning forms of dress to hysteria about “Sharia” arbitration courts appear rational. It makes politicians and feminists more interested in a piece of clothing than the women who wear it.

The photographs posted by these visibly Muslim women in their counter-protest raise some awkward questions. Who speaks for Muslim women? How did “freedom” and “choice” come to be the key terms in the debates about Muslim women’s rights? And how did Islam come to be blamed when a simple look around would confirm that Muslim women’s lives, political views and social positions are so diverse?

The problems they face are clearly shaped by many factors besides Islam, which itself is a constantly changing and contested tradition.

There is a long history of negative western representations of women in the “Orient”. Popular media have been breathing new life into these images ever since liberating the women of Afghanistan was offered as a rationale for military intervention. In 2001, I was suspicious of this justification for war, a justification that former first lady Laura Bush along with former secretary of state Hillary Clinton resuscitated last week in the face of the dismal situation in Afghanistan.

As an anthropologist who had studied and written about women and gender politics in the Muslim world for 20 years, I could not make sense then of the gap between what I was seeing in the media and what I knew from experience. I wondered which Muslim women were imagined as the objects of such humanitarian concern. Could one lump together refugees begging on the streets of Beirut with prime ministers of populous Muslim countries?

What of the differences between sophisticated women who head major international educational initiatives in the Gulf and the learned religious scholars who head the major women’s seminaries in Iran?

Thanks to the work of feminist scholars, we are aware of the long histories of women’s activism in places such as Egypt, Iran, India, Morocco, Palestine and Syria. Don’t the dynamic women in these organisations, or in other political movements that are not explicitly feminist, count as Muslim women? Even more intriguing, what are we to make of the new developments in what many are calling Islamic feminism? There are efforts under way across the world to offer new interpretations of the Quran, to teach Muslim women their tradition, and to argue for reforms of family law and justice within the faith.

It should come as no surprise, then, that young educated Muslim women joined Muslimah Pride Day to challenge the ways others were speaking (up) for them. That Afghanistan has been a battleground for the past 35 years is not incidental to the problems that Afghani women and girls face today. One must not ignore the global circumstances that shape their lives, even if one is aware that gender expectations may be unfair or that some groups are using “tradition” or religious authority to assert power over them.

Even in the Upper Egyptian village in which I have been doing research for the past 20 years, women with little or no education seem more aware of the sources of many of their problems than those who blame religion or culture, or the veil. A woman brought home to me the problems with this framing. One day in December 2010, we were drinking tea and catching up on each other’s news. I had been away for a year. She knew I had spent 10 years writing a book on the politics of Egyptian soap operas, based on research in her village. She and her children had helped me. She asked about the subject of my new research.

I said I was now writing a book about how people in the West believe Muslim women are oppressed.

She objected: “But many women are oppressed! They don’t get their rights in so many ways – in work, in schooling, in …”

I interrupted her, surprised by her vehemence. “But is the reason Islam? They believe that these women are oppressed by Islam.”

It was her turn to be shocked. “What? Of course not! It’s the government,” she said. “The government oppresses women. The government doesn’t care about the people. It doesn’t care that they don’t have jobs; that prices are so high that no one can afford anything. Poverty is hard. Men suffer it too.”

It was just three weeks from the day that Egyptians would take to the streets and the world would watch, riveted, as they demanded rights, dignity and the end of the regime that had ruled for 30 years. Her reaction to the subject of Muslim women’s rights confirmed something I had seen across the Arab world. She lived with hardships. But she was always analysing her situation and thinking about how to do the best for her family.

This impressive mother of seven, dressed in her black peasant robes and headcovering, deeply absorbed in her community and fiercely moral, had recently started a business. She had always managed very complicated affairs but the decisions and responsibilities weighed heavily She was acutely aware of the political circumstances that shaped her life and her possibilities, whether from living in a security state or from being part of the international tourist economy. Her shock at my suggestion that anyone would think Islam was oppressive was telling. Her faith in God and her identity as a Muslim are deeply meaningful to her.

So why are conservatives, progressives, liberals and radical feminists in the West convinced that Muslim women – everywhere and in all time periods – are oppressed and in need of rescue? Why can’t other voices be heard? Even more troubling, why does it seem so hard for them to focus on the connections between worlds instead of imagining Muslim women as distant and unconnected to themselves?

A moment’s thought and a glance at modern history would remind us that we live in an interconnected world. What happens to women in places like Afghanistan is shaped by what goes on in New York, Washington and Moscow. At the crossroads of competing empires, Cold War conflicts and current geopolitical interests, militarisation, political rivalries, the business of development and humanitarianism, and the economics of the arms and drug trades that tie us together are as significant for women’s rights and livelihoods in Afghanistan as something called Islam. And that is just Afghanistan. Other places have different connections and histories.

I’ve been trying to figure out why so many intelligent and well-meaning people who care about justice and rights feel it is morally right to intervene in the lives of women they perceive to be so different and so separate from themselves, ignoring the persistence of gender inequality and cases of violence against women in all societies, the many things we share as humans trying to live fulfilling lives, and our responsibilities to each other.

I worry that Muslim women are being used as pawns in dangerous imperial political ventures, in internal power plays within various nations and in racist anti-immigrant politics in Europe, the very setting of the Femen topless jihad against Islamism.

Lila Abu-Lughod is professor of anthropology and women’s studies and director of the Middle East Institute at Columbia University in New York. She is the author of Do Muslim Women Need Saving?, published by Harvard University Press