Among a montage of pictures celebrating cricket's greats at the indoor nets at Lord's, which still is surely the most renowned seat of learning in the sport, lies a perfect testament to evolution.

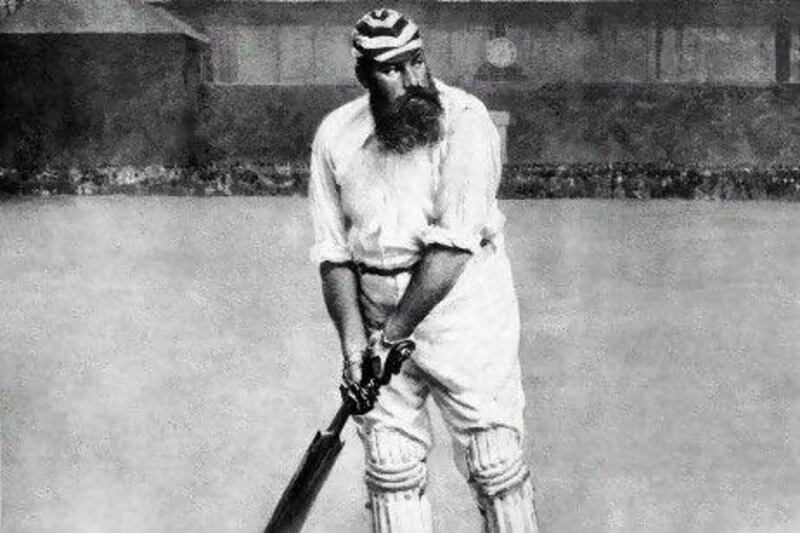

The photograph is of WG Grace, the superstar batsman of Victorian England, swinging his bat back ready to address the ball.

The image is instructive as to how far the game has come for lots of reasons, but one is strikingly more relevant now than the others.

There is this big, bushy beard, unusual in today's game, but not totally alien - look at Hashim Amla.

The blemish-free whites seem quaint, devoid as they are of logos for insurance brokers or mobile telephone companies. The bat looks a touch unwieldy, but it is still made of wood.

However, the most pertinent point about this picture is Grace's stance at the wicket. It is diabolical. His feet are planted, his knees are rigid. His trousers might have seen a forward press, but he hasn't.

From the black and white evidence on show, he is an absolute raging certainty to be out lbw. But then, that would never happen, would it?

Stories are legion about how difficult it was to dismiss the good doctor, even by the clearest means, let alone by getting the umpire to agree to a leg-before appeal.

Hawk-Eye, for one, would have had no chance. You can imagine the scene. Lbw appeal. Turned down, naturally. Bowler deigns to review the decision. It is found to have been hitting halfway up middle-stump.

Grace stands his ground, though. "See all these people?" he would intone. "They have come here to watch me bat, not you play with your digitised ball-tracking gizmo."

Existing in the time in which he did, Grace did not do too badly, even with the iffy stance. Which goes to show: evolution happens, so deal with it.

All this harrumphing about the Decision Review System changing the game, on account of the fact a slew of lbws are being granted where once they would not have been, is rooted in truth. But that does not mean the game has changed for the worse.

It is fitting that a beleaguered England team, who have spent as much time so far this year trying to come up with ways of combating the DRS as they have their opposition, will meet a revivedSri Lankan one at the P Sara Oval in Colombo tomorrow.

Thirty years ago, the island nation made their bow in Test cricket when they hosted England at the ground.

That week, the Asian novices were undone by a canny off-spinner, John Emburey, and one of the all-time great left-arm spinners, Derek Underwood, in a comfortable seven-wicket win for England.

How the wheel turns.

Lately, the Sri Lankans have been the ones doing the bullying, and they have only needed a couple of workaday slow bowlers to do it, too.

There is no greatness in the attack which ripped through the English batting line up in the first Test.

By coincidence, the P Sara is also the home ground of the Tamil Union, the club side of international cricket's most prolific wicket taker, Muttiah Muralitharan.

You wonder quite what trouble England would have been in were Muralitharan still around, given they have been done for in four consecutive Tests against spinners who are not in his class.

Maybe Sri Lanka have just the right resources for the DRS age, though, in the form of spinners who turn it less, such as Rangana Herath, the left-arm destroyer who picked up 12 wickets in Galle last week.

Muralitharan, and Shane Warne before him, made giving the ball a rip fashionable. Now, though, the DRS has shown up big turn as being no more than frippery.

England's problems this winter have not stemmed so much from the ball that turns viciously as the ones that have gone straight.

Abdur Rehman, for Pakistan, and now Herath have profited from sewing doubts rather than bowling grenades, and they have met with insecure batsmen who have got their pads in the way too often.

There were a world record 43 lbws in the three Tests between England and Pakistan in the UAE at the start of 2012. Rehman has taken 29 per cent of his Test wickets to date by that mode of dismissal, while 26 per cent of Herath's have come in the same way.

That contrasts markedly with two bowlers more noted for the amount of spin they exacted on the ball: Warne was at 19 per cent, Muralitharan 18 per cent.

Conventional wisdom and geometry suggests left-arm around the wicket bowlers are more likely to dismiss a right-handed batsman lbw - but never so much as in the DRS age.

Only eight per cent of Underwood's wickets came that way, while Bishan Bedi, the great Indian slow bowler, took six per cent of his by the method. Playing spin, and batting in general, should be facile: see ball, find gap, hit ball, manoeuvre ball into gap.

Clearly, it is not easy, or we would all be scoring Test hundreds all of the time. But those who score the most do manage to make it look that simple, such as Younis Khan in Dubai earlier this year, and Mahela Jayawardene in the Test in Galle.

Simply put, England's batsmen need to find a method of getting their bats to the ball before their pads.

Or they could just grow a long beard, use a lump of 19th century willow, and try to persuade the television official that they are not allowed to give them out, because everyone is there to watch them bat.

Follow us

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]

& Paul Radley

[ @PaulRadley ]