There is a certain brutal honesty about a set of rules that begins with its exception policy.

You do not have to delve too deeply into the 85-page sleep assistant that is the Uefa Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play (FFP) Regulations to get to the get-out clauses.

Skip the preamble and definition of terms, and there it is in the very first paragraph of regulations proper. "The Uefa administration may grant an exception to the provisions ... within the limits set out in Annex I."

It turns out to be quite a list of ways out for clubs concerned they may breach the FFP principle of bringing spending into line with income at the cost of expulsion from Uefa club competition. The best one seems to be big and popular.

"The status and situation of football within the territory of the Uefa member association will be taken into account when granting an exception," Annex I reads. It then details key factors like the size of a club's home country and football association; its average attendance, television market, sponsorship and revenue potential; and its support from national, regional and local authorities. It could almost have been written for a Barcelona or Real Madrid.

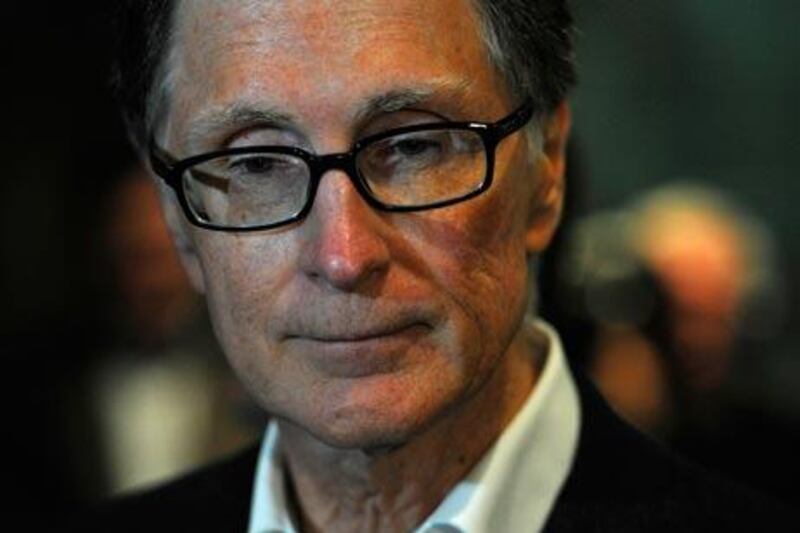

One problem with a policy built upon the laudable premise of encouraging football clubs to operate sustainably is that it has always been a political exercise. Michel Platini believes profit-driven investors buying clubs with borrowed money, as Tom Hicks and George Gillett did with Liverpool, was inherently dangerous. Neither does the Uefa president like the inflationary effects of a takeover and overhaul by a wealthy foreign buyer.

Being the easiest of the grand European leagues to buy a football club in, the English Premier League's stance to FFP has been one of resistance from the beginning.

Recently it went public on a request for special dispensation based on the league's - unilateral - decision to ban third-party ownership of players; one that effectively increased recruitment costs. Officials argue that English clubs are disadvantaged in several other ways.

Politics, however, function internally too. Both Arsenal and Liverpool love the idea of FFP and want it rigorously applied both to European and domestic competition.

John W Henry and his consortium of profit-driven fellow American investors bought into Liverpool on the premise that European-wide financial regulation would help reassert their purchase as one of England and the continent's most powerful clubs.

It seems they did not read the get-out clause.