The first time the subcontinent hosted a World Cup, in 1987, teams still wore whites. The garish kits came four years later.

The games in India and Pakistan attracted huge crowds, but cricket had not yet become the vehicle for jingoism or the commercial behemoth that it is now. Those were simpler times.

When Pakistan lost their Lahore semi-final to Australia - Craig McDermott took five for 44 to trump Imran Khan's three for 36 and 58 with the bat - their inspiration captain consoled himself by listening to the Rolling Stones' You Can't Always Get What You Want.

By the time cricket's showpiece event returned to the region less than a decade later - Sri Lanka triumphed in the Lahore final - the pressures on players were very different.

When Pakistan lost to India in a highly-charged quarter-final in Bangalore, Wasim Akram, the captain who had sat out the game with an injury, was accused of fixing and his father kidnapped and beaten up by bookies.

When India's campaign ended at the next stage on a diabolical Eden Gardens pitch, the capacity crowd reacted by starting fires in the stands, forcing the match to be abandoned.

The stakes are even higher now, with irresponsible media stoking up parochial feeling and equating sporting victory and defeat with a nation's pride.

When the 14 captains addressed the media before yesterday's opening ceremony, MS Dhoni spoke of how it made no difference which team India played.

The pressure of expectation remains the same.

Failure will result in burning effigies, vandalised houses and a few idiots waiting outside the airport terminal with rotten eggs and tomatoes.

In 1987, the two host nations gave their fans much to cheer. India lost their opening game to Australia by one run, but were otherwise rampant.

In their final group game against New Zealand, they confirmed top spot in the group with Chetan Sharma taking a hat-trick and Sunil Gavaskar scoring an 88-ball 103, a remarkable statement from a man derided for batting all 60 overs for 36 in the first ever World Cup game.

Pakistan won their first five matches, with Courtney Walsh, the West Indies bowler, famously choosing not to run out Saleem Jaffar as the batsman was backing up from the non-striker's end, in a match that was to have a huge bearing on the Caribbean giants failing to qualify for the semi-final for the first time.

But within the space of just 24 hours in Lahore and Mumbai, hopes of a dream final in Kolkata evaporated.

For the old world, it was still an occasion to savour. Instead of Pakistan and India, those that thronged the stands watched Australia take on England, conquerors of India in Mumbai. Chasing a stiff total inspired by Graham Gooch's sweep-filled hundred, India unravelled under pressure. In his final match for India, Gavaskar made just four.

By 1996, the Kapil Dev-Imran generation had given way to the Sachin Tendulkar-Akram one, but again, the region's most reputed teams could not handle the weight of expectation.

Instead, it was tiny Sri Lanka, masterfully led by the Napoleon-like figure of Arjuna Ranatunga and boasting an explosive batting line-up, that upset all calculations.

A generation on, only Muttiah Muralitharan remains from that victorious XI.

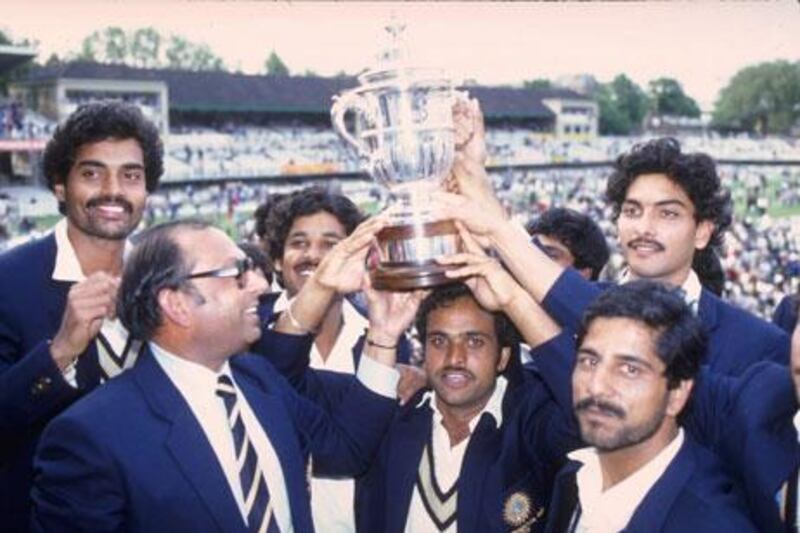

For India, Tendulkar, who played his first World Cup as an 18-year-old in 1992, still remains, the last representative of the generation that grew up inspired by India's improbable success of 1983 when they beat the then-mighty West Indies in the final.

Sourav Ganguly, Rahul Dravid and Anil Kumble were all in the squad when India failed at the final hurdle in Johannesburg eight years ago.

For a generation that has grown up with stories of 1983, that triumph is fast assuming the proportions of a fairy tale.

And with uncertainty surrounding the very future of the 50-over game, who knows if the subcontinent will see another World Cup?

It took Imran five attempts to land the biggest trophy in the one-day game.

This will be Tendulkar's sixth, and surely last, World Cup. In the two decades and more that he has represented India, he has attained a status far beyond that bestowed on his childhood heroes.

As he approached a double-century against South Africa in Gwalior last year - the first man to achieve the feat - television channels cut away from regular programmes to keep track of his progress.

Next to him, even Bollywood's megastars are nonentities. Not since Mahatma Gandhi has an Indian been so adored.

For India to give him the perfect one-day farewell though, sentiment and pressure will have to be kept at bay.

The lessons of 1987 and '96 are there to remind everyone that in this heat and dust, only cool heads prevail.