When Livorno gained promotion back to Serie A last summer, there was one fixture that they anticipated with more than the usual relish. Tonight, after a two-year gap, it arrives and their fans will march on Rome while the Carabinieri hold their breath and cross every one of their fingers. Lazio versus Livorno is a game with baggage. On the field, positions in the lower end of the table are at stake. In the grandstands, the contest is about ideology, or at least that is how this fierce rivalry dresses itself up. Livorno are known as a communist club, whose fans do not just take scarves, replica jerseys and loudhailers to matches, but go with Che Guevara insignia in tow.

His face, emblazoned on banners and T-shirts, is the chosen signature not just of a club, but of a city as strongly associated with the political left as any on the Italian peninsula. As for Lazio, their fame as a club with right-wing leanings has been around since the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini used to watch them. Incidents of bigotry among their ultras frequently embarrassed Lazio in the 1980s and 1990s, when racist graffiti greeted the arrival of the club's first black footballer, Aron Winter.

In Italy, the relationship between football and political allegiance tends to be more conspicuous than elsewhere in western Europe. But in the land where governments lurch from one complicated coalition to another, allegiances are never straightforward. Traditionally, most of the big cities defined their rivalries by left and right: Roma were reddish in inclination, Lazio conservative; in Turin, Juve leaned to the right, Torino to the left. Milan were once supposed to incline more to the side of the proletariat than Inter, although the 21st century - and the arch-conservative Milan president Silvio Berlusconi - has rather challenged that historic notion.

Beyond the tycoon clubs, you find more fiercely defined associations. Ascoli, Verona, Padua and Triestina have right-wing ultra reputations. Bologna, Brescia and Genoa are associated with the left. And sometimes this is not just a question of mild banter between fans. Far from it. A recent study commissioned by the anti-hooliganism division of the Italian police found that of the 128 clubs that make up Italy's top three divisions, 42 had significant political orientations in their fan base.

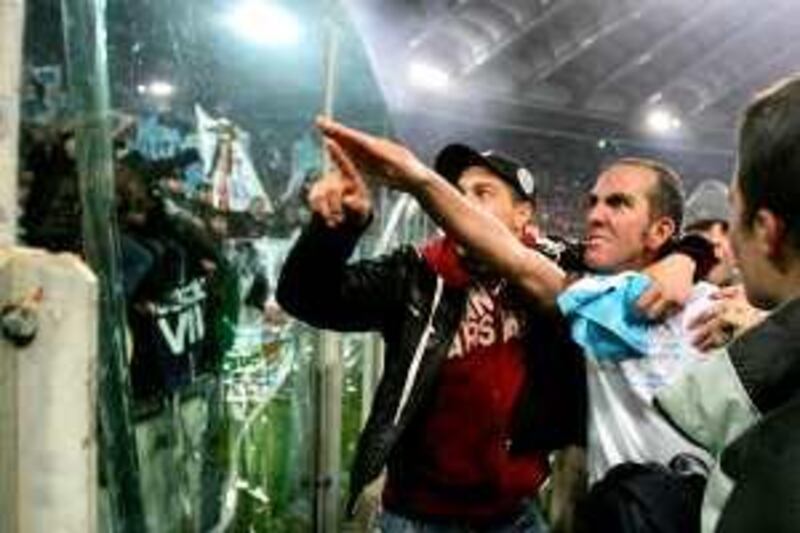

Twenty seven clubs veered significantly to the right, 15 to the other extreme, and seven were simply extreme, with radicals of both hues among their contingent. So the authorities will be anxious this afternoon at the Stadio Olimpico, lest two seasons of absence from one another's company in Italy's top-flight has pent up too much agitation from both sets of supporters. Previous encounters have featured some provocative gestures and words from conspicuously political players, like the former Lazio striker Paolo Di Canio; a man proud of his right-wing principles, and Cristiano Lucarelli, the Livorno striker who boasts about his strong socialist beliefs. Still in the memory are the scuffles around meetings between Lazio and Livorno from the Tuscan club's last stay in Serie A.

After one such episode, Livorno's stadium was left with damage to the toilets and seats at the away end: Livorno immediately sent a bill for the repairs to Lazio's head office. sports@thenational.ae Lazio v Livorno, 6pm, Aljazeera Sport +6